Creativity and imagination are key steps in the process of doing science or creating art. And yet, in the sciences, we often don’t talk about how important creativity and imagination are and were to our research questions, findings and breakthroughs.

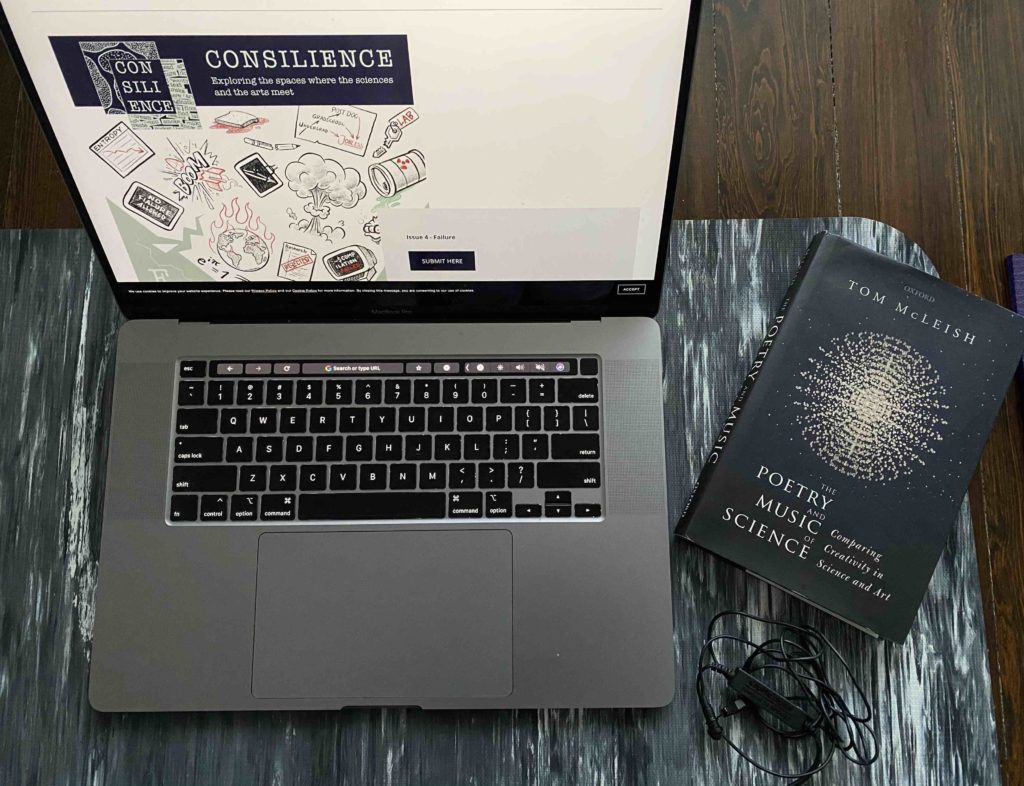

Lifeology’s January Science Communication Challenge asks scientists and science communicators alike to reflect on and share creative experiences, or “a time when creativity, imagination or subconscious thought was important to your scientific or artistic work!” Today, I hope to inspire you to take this challenge through an interview with Tom McLeish, author of “The Poetry and Music of Science – Comparing Creativity in Science and Art.” Below, you can read my conversation with Tom about creativity in science, why it is important and how to explore it for yourself! You can also listen to the full interview here.

“There is not a scientific way of thinking and an artistic way of thinking. There are visual ways, and textual ways, and abstract ways, but each of those ways jump between artists and scientists.”

Tom McLeish has been a working scientist for over 25 years. His area of work is soft matter, which is exactly what it sounds like – the study of jellies, rubber, sticky stuff. As he says, there is a massive amount of physics to these delicate arrangements of stuff. He also often works as a part of interdisciplinary teams that include physicists like himself as well as chemists, chemical engineers, computer scientists and others.

What got you thinking about creativity in science?

Tom said he got interested in creativity in science from his science outreach work in schools.

“I got really sad when I spotted a pattern, where very bright, capable students, who could have done anything they wanted to, would say when I asked them [why they didn’t go into the sciences], ‘I didn’t see in science any room for my own imagination or my creativity.’ That went through my heart like a knife. We’ve done something terribly wrong if we’ve given the impression to young people that science doesn’t draw on imagination, or that being a scientist can’t be creative. Because without creativity, as any practicing scientist knows, it is a non-starter. We’ve given the impression that science is about filling out a spreadsheet or following a recipe to get the right answers. That’s not how science works at all. It is far more about questions than answers. It is about reimagining the universe from our observations, by extrapolating… it is about all those things.”

“That is what got me first interested in creativity in science. And then I started to reflect on my own career and asking myself, did anyone teach me this or give me help on how to become a more creative scientist, to help me come up with more creative ideas? This made me start to think more about how we can help the next generation of scientists understand creativity.”

Why is it important for scientists to think and communicate about opportunities for and their own experiences of creativity in science?

“There are many reasons… but to start with, it helps everyone, even people who are never going to be scientists. We have a problem, in that science today has this sheen of expertise and geekiness.”

Tom said that many people see scientists as being “other” and “weird.” But to Tom, science is – or should be – like music. Everybody likes music in one way or another. We all find ourselves humming our favorite tunes in our heads. We can appreciate music (even create it!) without having to be experts.

“You don’t have to be an expert musician in order to express an opinion about or think about music, to be a critical audience of science, to engage. Why isn’t it like this in science? It should be. Yes, of course, there is expertise within the profession, just as there is in music. But in science, there isn’t this continuous ladder of expertise like there is in music, with everything from kids in school orchestras, to amateur musicians like me, to professionals like my daughter and son who are training in London now. [We don’t leave room for] the amateur, engaged, creative scientist.

“By not communicating about creativity in science, we are also missing out on some of the brightest, exciting, creative scientists, who are not entering the field because they got the wrong idea of what science is.”

“And finally, experts within the scientific community itself today also need to be thinking about how we can be creative. Einstein, Heisenberg… many of the greatest scientists have said over and over again that the key step in creating a new understanding of the universe is asking the imagination question, not just coming up with answers. Of course, we give the impression in school that good science is coming up with the right answer. I often have to say to young people coming to do their PhD studies with me, ‘I’m terribly sorry, I apologize on behalf of the scientific community, we spent the last 15 years training you to be the best in the class at coming up with the right answer. The bad news is that is going to be completely useless to you from this time forward! Because now, what you have to do is coming up with a really interesting question!”

How do you see creativity working into science, and why aren’t more scientists seeing or communicating about the importance of this step? Are we misleading ourselves to believe there is a very formulaic process to good science?

“It would be boring if science were just deductive. Science is inductive, too. The closer you get to the heart of what goes on in science, the more you realize that there is no single scientific method. If there were a ‘Scientific Method,’ I would have had a course in it, right? Well, I haven’t. Ever. But if there were one, we’ve been taught that it goes like this: You have a hypothesis, the hypothesis leads to some predictions of what happens if I do this or that, so you do some experiments or you make some observations that might support or refute your hypothesis, and then you begin again. Fine. But nobody said where the hypothesis came from in the first place, did they? That’s the central creative step. There are no rules, there is no method, there is no recipe for how you come up with a hypothesis.”

“There is Heisenberg. Absolutely exhausted emotionally, practically depressed and about to have a breakdown. He goes on holiday to an island in the Baltic. He’s totally puzzled with all of this information that no one understands, spectra from atoms. And then some extraordinary idea bubbles up in his head, that we have to think about position and momentum in entirely new ways. And suppose we thought of momentum as not a number, but as an operation on an atom. You could imagine this, and it wells up from the depths of a subconscious, fed by every angle of your experience. That’s what scientific creativity is. And in small ways, we’ve all experienced it.”

This passage from Wiki highlights the role of imagination, “leisure” time and conversations with others in scientific discovery!

“Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) first formulated the equation underlying his picture of quantum mechanics while on Heligoland [see image above, Heligoland about 1929–30, by Archiv Spurzem] in the 1920s. While a student of Arnold Sommerfeld at Munich in the early 1920s, Heisenberg first met the Danish physicist Niels Bohr. He and Bohr went for long hikes in the mountains and discussed the failure of existing theories to account for the new experimental results on the quantum structure of matter. Following these discussions, Heisenberg plunged into several months of intensive theoretical research but met with continual frustration. Finally, suffering from a severe attack of hay fever, he retreated to the treeless (and pollenless) island of Heligoland in the summer of 1925. There he conceived the basis of the quantum theory.”

Tom recounted one of his own “epiphany” moments.

“I remember being in a seminar talking about the physics of proteins, and going into a sort of semi-trance. It was really weird, I was just ‘dazing off’ as you might call it. And I remember that in my mind’s eye, I saw this fixed picture of a protein molecule – with atoms, hydrogens and nitrogens and carbons all twisted up – that started to kind of oscillate randomly, with this thermal oscillation we call heat. And I started to see or imagine what sorts of consequences for information, transferring waves across this thing would look like. That gave rise to 10 years of fruitful research.”

Are scientists leaving enough time in their day for these creative steps? Artists seem to have a creative process that leaves room and time for this creativity – could scientists benefit from the same?

“That’s true… I think there are several problems. We don’t leave enough contemplative, immersive time in science. We don’t talk ourselves off for walks and just free wheel a bit. There are also problems with computers. For experiments, computers are obviously fantastic tools, but they are far better servants than they are masters. If they get in the way of our experience or engagement with nature, then that’s a bad thing. Sometimes I think we switch our brains off [and let our computers do the work].”

“I once listened to a wonderful talk by a Nobel Prize-winning biologist, who stopped halfway through his talk in a packed lecture theater to say, ‘What really worries me is that all you young scientists don’t spend enough time looking, just looking, anymore. You are so pressured to get results. Can I just beseech you to look down your microscopes for hours and hours, just look.’ I thought that was just lovely and deeply poetic. This was a heartfelt plea for scientific imagination.”

“This seems to be a very artistic thing to me as well. Both science and art work on these rhythms. If you are an artist, you spend hours and hours on the technical side, laying down oil paint, getting colors right, working through technical issues with trial and error. This is very much like the process of scientific experimentation.”

But both in science and art, Tom said, we need to allow time for “epiphanies” that bubble up from our subconscious mind when we aren’t necessarily focused on the nitty-gritty details and technical process of doing our science or creating our art. This reminds me very much of an episode of Abstract on Netflix, where illustrator Christoph Niemann shared his experience creating a cover for New Yorker and how important reflective time, walks and random interactions were to his art.

“It’s all the nitty-gritty experiences that happen consciously that then sink down, if I may use a metaphor, into our subconscious, and are then processed there as raw material. Then there are other little moments where our subconscious, which speaks very quietly, tries to communicate these ideas back upstairs. If I had five pounds for every time someone said to me, either an artist or a scientist, that ‘I was getting off of a bus when…’ or ‘I was in the shower when…’ or “I was on a run when I thought, oh yeah…’ My main advice to any scientist is to travel by bus, everywhere! Short trips, keep getting on and off! My amateur theory for this is that most of the time, our conscious mind is completely absorbed with our current environment, processing and interpreting what we are seeing and hearing. It is too busy to listen to our subconscious. But when we are changing environments – like getting off of a bus – we are literally in neutral just for a moment, which means we aren’t doing all this interpretive work. It is in these ‘limbo’ moments that our subconscious can speak to us.”

We are also “trained to cover our tracks,” Tom said, in terms of talking or writing about these moments of inspiration in our scientific manuscripts, and how these moments informed our scientific ideas and hypotheses. There are rare instances, however, when scientists stand up to tell us how a given idea or breakthrough or research finding really happened. These stories are refreshing and intriguing.

“It is so rare to hear the real, deeply human stories of science, which are often about relationships, love and quests.”

We need to communicate these stories more often to broader audiences and to each other, Tom said, because they help to manage the expectations of young scientists who are often led to believe that asking the relevant questions and getting the right answers is easy and straightforward.

“In the words of Wordsworth and Coleridge, there will be a day when poetry responds to science, but only when the experience of the scientist is conveyed as a suffering experience, conveyed, enjoyed and shared by people at large. And Peter Medawar said something similar – that the difference between artistic and scientific creativity is that the scientific imagination doesn’t carry, it stays within the scientist. But with the artist, it transports, it is carried [to others]. Well, there is no reason that should be true! I think that is part of our problem.”

Do you have advice for scientists, on how they can start telling these personal stories of science, stories of creativity and imagination?

“The simplest advice is to start telling the truth. We don’t have to make things up or try too hard, you just have to be more honest than we [scientists] normally are when we get up at a conference and say, ‘we did this, we did that, and we came up with these answers.’ We omit to say that for years we got nowhere by doing these other things.”

“I think it would also be great if we started having more conversations with artists. I think what you are doing to bring artists and scientists together is absolutely fabulous. I’ve enjoyed working with several artists over various projects – including one who introduced me to square cogs, which I had no idea existed or could work! I’ve learned a lot of math and engineering from artists. But the important thing is that by sharing our stories with one another, we not only provide each other with new ways of thinking creatively, but we are better able to spot patterns of creativity and discovery that are shared between the sciences and the arts.”

Tom also encourages scientists to try different communication formats – keep a diary, write a poem, doodle! Trying these other forms of communication, and having the courage to try, may open your mind to creativity in your day to day and help you communicate how this is part of your science.

Inspired? Write or draw a story about a time when creativity or imagination was key to your own science or science art! Take the challenge here.