Cartoon by Virginia Schutte.

Advice columns for scientists are full of should’s when it comes to science communication: PhD students should have a science communication-focused committee member, scientists should be on Twitter, social media is a waste of valuable research time, scientists should be communicating their work, scientists should leave the communicating to the professionals… All of these imperatives can muddy the waters. But if you listen to one “should”, perhaps make it this one: Tell stories. Research findings in the field of the science of science communication are clear on this front: storytelling engages people and changes minds whereas rattling off facts does not.

Telling a science story can seem like a daunting task. If you’d like to learn more, I suggest starting with this episode of Greg Foot’s ‘Talking Science’ YouTube series. Other great resources are this list of technical storytelling tips and this blog post and this presentation that describe many types of stories that might be relevant to scientists. If you’re looking for in-depth inspiration, check out this collection of pieces that dissect published stories in detail to determine what makes them so compelling and how the storytellers created their pieces.

So let’s assume that you have a science story to tell. Now what? What should you do with it? Where and how should you share it?

It depends on the story.

The first thing to ask yourself is: what kind of story do you have? Most science stories fit into these broad categories:

1) A research breakthrough: You discover something previously undocumented in scientific literature or update our understanding of an issue.

Even though all published research moves science forward in some way, not all publishable units will be right for broad sharing. Some published findings need to be combined or stripped down for sharing with broader audiences, while others may not be compelling enough to pursue a sharing strategy for. If you can answer yes to both of these questions, then you’re probably ready to move forward with sharing your breakthrough: Do you have a story in mind with a clear beginning, middle, and end? Can you articulate why an audience will care about this story?

If you’re unsure whether your science breakthrough is right for sharing, then keep in mind that the time you spend on a story is time you’re not spending elsewhere. Also remember that many storytelling relationships are built on quality partnerships; bombarding communicators and reporters and audiences too many times will eventually dilute the most powerful messages and cause people to tune you out. If you’ve deeply thought about these points and are still convinced that sharing your story will be worth everyone’s time and energy, then you’re probably right!

2) A research update: You are in the process of doing science and have science-related updates on methods, preliminary results, etc.

The best time to get target audiences interested in your stories is as soon as you can. If your methods lend themselves to multimedia campaigns through photography, art, videography, social media updates, etc. then there’s no better time to start gathering and sharing storytelling media than now. This video I made is a great example; it describes the researchers’ system and research setup, which gathered an interested audience before the research results were even collected. Are you collecting samples from an unexpected location? Do your lab methods become art when photographed up close?

3) The process of science: You and any organisms you work with may make stellar subjects.

These stories focus on development of a character or a description of the systems that you do your science in rather than the research and its outcomes, although research particulars can certainly be included if relevant. The Story Collider offers a master class in how to tell true, personal stories about science; see this episode, for example, about working in science and doing the right thing.

Cartoon by Virginia Schutte.

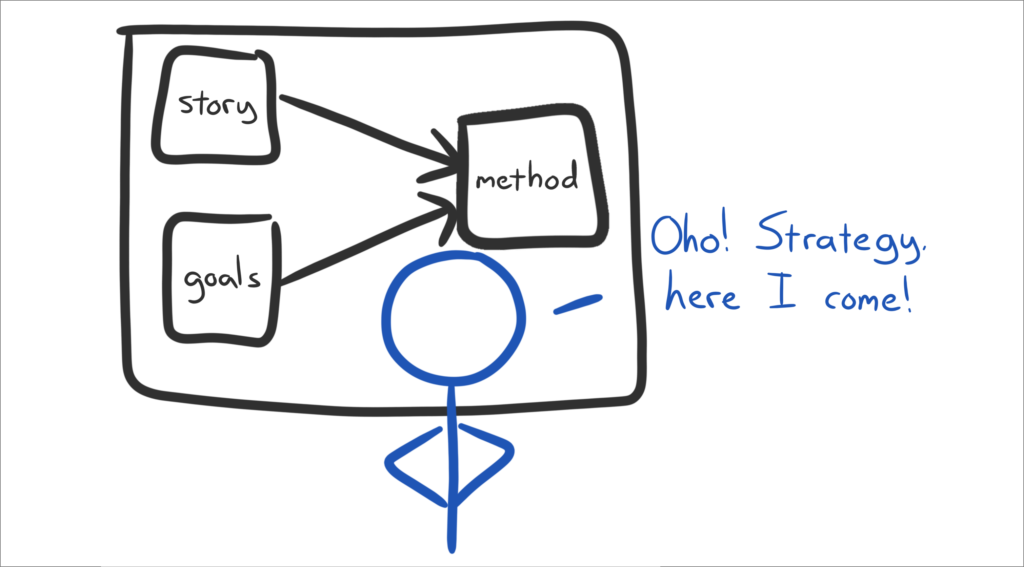

It depends on the audience.

A close second question for you to consider is: what audience would you most like to interact with your story? Each of the story types above could target multiple audiences, depending on the goals you have for sharing your story:

1) A research breakthrough could be shared with federal or state policymakers, legal advocates, household decisionmakers, educators, local community leaders, and others.

2) A research update could be shared with potential donors/funders, family and friends, interested stakeholders (like those running a facility that you’re using for your research), people who might be interested in the research outcomes once your work has concluded, non-scientists who care about your research topic, and others.

3) The process of science could be shared (as part of your mentoring portfolio) with trainees, graduate students, undergraduates, colleagues, administrators, policymakers, and others.

Who do you want to reach with your science communications?

It depends on your science communications goals

Finally: what’s the best method to engage your target audience? Notice that I’m using language like “engage” and “interact” with an audience. Storytelling often begins with a one-way broadcast, but there are many ways to get people involved beyond asking them to read. Which method is most effective depends on your storytelling goals, your target audience, and your source material:

1) If your goal is to influence a policymaker by sharing a research breakthrough, then a white paper or policy brief would work well.

2) If you have a research update to share from a tech-heavy project, then an explainer video posted to YouTube but embedded on sites like Wired or Gizmodo may connect you best with technophiles.

3) If you’d like to reach teens with a story about the process of science, you may want to get an edited photo or meme-style video on Snapchat or Tiktok. Or you could reach their parents through Facebook or a subscription outlet like a newspaper or magazine.

4) If reaching people with low literacy or non-English speakers is a priority, you might consider creating a visually-oriented course here on Lifeology.

Example cards in a Lifeology course.

It depends on why you want to tell your story

So perhaps the most important question you should answer that ties it all together is: why do you want to tell your science story?

There are a lot of storytelling options beyond press releases that can help you meet a lot of goals beyond telling people about published papers. Though it can feel intimidating to navigate the ever-changing science communication (“scicomm”) media landscape, remember that you are not alone. There is likely at least one person at the institution you work with whose job description includes helping you tell your science stories.

Need help? Work with someone like me!

I help scientists tell their stories by creating websites or website materials; gathering photos and videos of your research while it’s happening; creating outreach products like social media posts, posters, games, or online courses; or by giving you confidence and skills to get funding for outreach and to carry it out yourself.

If you’d like to see what we could do together, connect with me – I’m a Lifeology coach! Click to Connect with Me (Virginia) under my Lifeology coaching profile and in the text box that pops up, let me know what story you want to tell and why, and what you need in order to share your story (media creation? training? advice?). Then we can chat to walk through how to make your story fit well into today’s media landscape!