Science communicators comprise a large group of people and span many roles and objectives. To name a few examples, science communicators are scientists interested in the public’s engagement with science, formally-trained science writers and journalists, and even artists who communicate science through their work. As science communicators, we are always looking for ways to engage our audiences with the topics we care about. At Lifeology, we use our flashcard courses, which combine storytelling and art, to communicate about science. As part of our new SciComm program, we even have a course based on storytelling called How to tell a science story. Below, a Lifeology community member, Cassidy Villeneuve, tells us about the advantages of storytelling—and getting personal—for topics that often come with controversy or resistance, such as climate change.

Scientists, SciComm, & Storytelling – Getting Personal

By: Cassidy Villeneuve

Humor me with some free association… What adjectives come to mind with the word, storytelling? Here are a few that I think of: Fictional. Sensational. Subjective. Personal. Powerful.

I’m not the first to suggest that scientists tell stories as a part of their science communication. And I’m not the first to sense a resistance to that. The call to tell stories about one’s research (and even one’s life) runs counter to how many scientists are taught to communicate their expertise. The personal is the enemy of the objective. And I understand that for many contexts. But I also hear widespread acknowledgement that the science communication we’ve all been doing is not reaching people well enough, fast enough, or at all. And with the prevalence of misinformation, it’s not necessarily about who is right. Rather, (in a simplistic sense) the public is drawn to messengers who appeal to their lived experiences, who they like, and who have the most screen time in the places (online and off) where they already spend their time. People trust scientists, studies show, but they also think scientists are drawn to the pursuit of knowledge at the expense of their humanity. Our culture assumes a dichotomy between cognition and emotion, which sets scientists up to seem robot-like and cold in the eyes of the public. Negative implications for the goals of science communication follow.

So how can scientists become more trusted messengers? How can we change stereotypes? You guessed it—storytelling. We need more opportunities to see scientists in their full humanity. I’m not a scientist—I should mention. I’m a storyteller. I recognize my bias here. But in the last few years, I’ve been learning from many leaders of science communication (Lifeology’s community among them), driven by the question of where my skills telling stories might contribute to our shared goals. We can all agree that communicating about science is an increasingly important mission given what humanity faces globally—a pandemic and climate crisis, and the inequities that both are surfacing and amplifying.

The calls to action that I’ve been seeing audiences remember and respond to most are ones that acknowledge their lived experiences, appeal to their emotions and values, and invite them into a collective movement through the language of hope

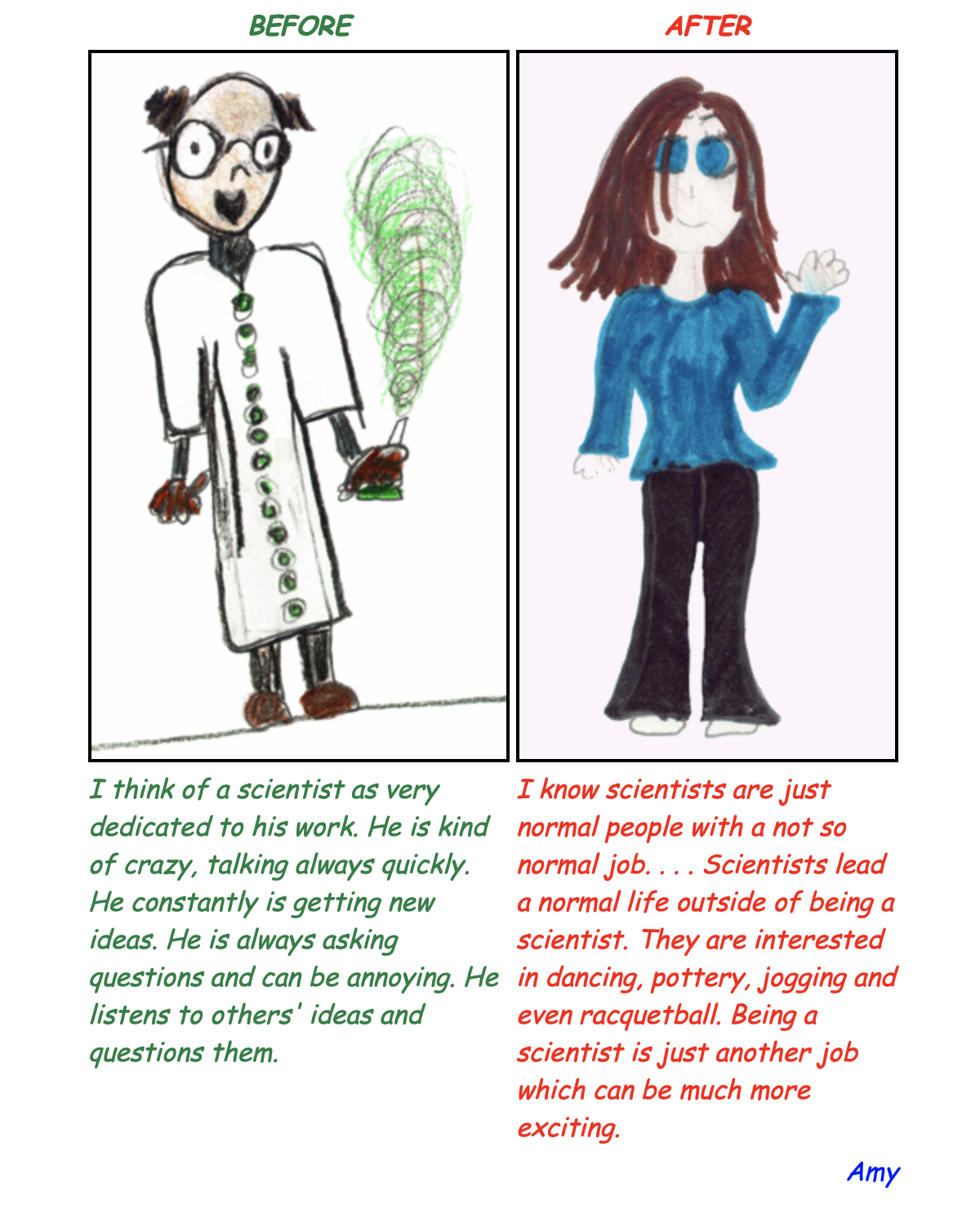

There are so many projects that already do this well. When kids hear personal stories from scientists, their previously-held stereotypes change. Take the much-replicated “Draw A Scientist” experiment. When students are asked to draw a scientist before and after being exposed to a real person, their drawings become more inclusive of folks beyond white men holding beakers.

7th grader Amy’s drawings from before and after her visit to Fermilab

Scientists who take selfies in the lab or in the field help change stereotypes, too, and foster trust. Scientists who share their backstory with public audiences, boost their credibility. And, as Susan Fiske and Cydney Dupree have found, to be credible in the eyes of a wide audience, scientists must exude both competence and warmth. Warmth, they found, may even be the more important of the two. It turns out, authenticity speaks louder than hard facts. Trusted messengers of truth tell the truth about themselves.

Storytelling is a way into hearts. It’s the basis of human connection and communication. It’s the tool by which we relate to each other, build relationships, teach our children, and advocate for ourselves and others. It’s about empathetic listening, knowing your audience, and understanding what barriers are keeping so many folks from participating in conversations about science to begin with. Inviting more people to care about science means acknowledging those barriers and working hard not to replicate them. Storytelling is a tool that transcends stereotypes and differences and, at the same time, acknowledges the unique experiences of both teller and listener. The beauty of stories is that the truth of them—the moral, the take-away, whatever you call it—is felt beyond words. Emotions are universal.

Some science is especially tricky to communicate to mass audiences, though. Few topics inspire more resistance than the words “climate change.” And it goes beyond who’s speaking about the issues. Our society’s frameworks for understanding this topic are so strong (and often misguided), that it’s difficult for much else to get through. Most of us learn about climate change through images of polar bears, not humans, giving us the impression that it’s a far away problem. Contextualizing a changing climate around what it means for humans roots the topic in something people without your scientific background can grip a bit easier: the desire to care for their families, friends, and neighbors. Because, as we know, the fight to save the natural world is as much a fight to save people.

Recently, I was lucky to help put together a storytelling workshop through StoryCenter for a group of women in environmental advocacy and climate resilience. 13 of us from across the United States, Canada, and beyond, joined weekly virtual meetings to create 2-3 minute video narratives about our connection to the natural world and ultimately, about why we do the work that we do. Through StoryCenter’s unique process (informed by community-based participatory media and testimonio practices), the videos that emerged were so deeply personal—about self, family, mentors, fear, loss, grief, violence, and love. Each embodied the intersection of racial, social, and environmental healing in ways that are too often missing from dominant narratives in the field. Storytellers took what we might think of as the “big themes” of environmental advocacy communication and gave them emotional depth, gave them human voices. In these workshops, people create art out of their experiences; they do not create messaging or curricula. Their finished stories do not tell their audience how to think or feel. Rather, they invite listeners to understand why the storyteller cares, to feel along with them. And the storytellers, in turn, process the toll that this work can take and are given a chance to be heard. Each time I am a part of something like this, I am reminded that amazing things happen when we are given the permission to tell the truth about ourselves.

This video by Scott Kalama was created in a workshop led by StoryCenter and coordinated by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and the Oregon Health Authority’s Climate and Health Program. Stay tuned for the release of the stories from the aforementioned workshop.

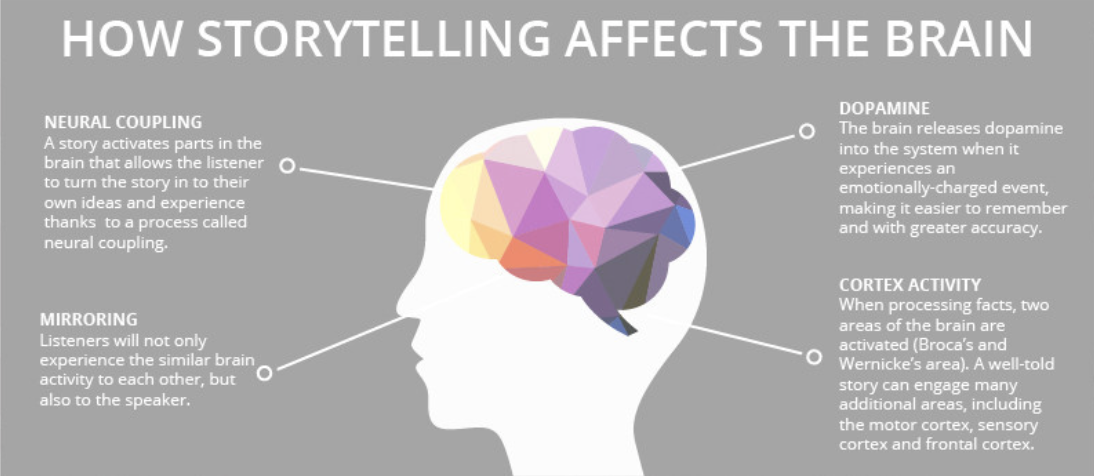

Storytelling is a universal language. “The beauty of it is that a good story, whether visual, spoken, watched or read, is felt before it is known,” writes climate justice writer Amrekha Sharma. And there’s science to explain these effects.

Infographic by Visualistan showing how storytelling affects the brain.

Storytelling as a pedagogical tool helps students feel more engaged and learn meaningfully. And in general, sharing stories can have a positive effect on the mental health of the teller. In science communication contexts, and in the workshop I was part of, stories are cathartic, important tools for processing climate grief, for feeling heard, and for witnessing others who are working hard toward noble goals. Our brains are wired to encode narratives.

The goals of science communication are varied. Perhaps you’d like others to benefit from science in their daily lives, to join STEM careers or participate more in science, to be empowered citizens, to support scientific advancement, to share in the wonder of our world, or to trust science.

No matter the goal, we must call upon all the tools we have to reach the people we want to listen to us.

“People’s imaginations are engaged in different ways,” says climate scientist and activist Dr. Mika Tosca. “Some people are really inspired by videos. Some people are really inspired by paintings or hanging artwork. Some people are really inspired by reading about it. We shouldn’t limit ourselves, and we should try to reach everyone in every way everywhere.”

Stories can:

- surface conversations and provide training around certain topics,

- mobilize local communities around social and human rights issues, or drive strategy,

- educate policy makers, leaders, and decision-makers (perhaps packaged in a policy brief or proposal), and

- show the public and folks responsible for policy enforcement what their role is.

So share your origin stories, your passions, your mistakes, your revelations. Reel your audience in. Explain complex topics using metaphor. Invite folks to care about what you care about. Stories don’t have to be the end all be all. They may be just a part of your message. And as with many forms of science communication, you don’t have to capture your entire research in one go. Let personal narrative lend a hand. And when you wonder, does my experience or story really matter? Know that if you can convey why it matters to you, it will matter to us.

Cassidy Villeneuve is a writer, graphic designer, and facilitator who helps build bridges between experts and the communities they serve. You can read more about her at her website or find her on Twitter @cassivillen.