My life has been shaped and guided by stories. Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov (and so many of his other books) opened up an insatiable curiosity in me about the human body, engineering and the microscopic/atomic world. That curiosity ultimately led me into a (short-lived) career as a biomedical engineer. But stories also led me out of science. In graduate school, I realized that doing science at the bench wasn’t nearly as exciting as my favorite science fiction books had made me believe.

Stories are powerful. When I entered the science blogging world in 2011, just a handful of stories from other bloggers – about how they had quit their science day jobs to become full-time communicators – literally changed the course of my life. Their stories inspired me so much that I promptly quit my Ph.D. program without much of a plan other than to move back to my alma mater and begin taking some courses in mass communication as a non-matriculated student. Others’ stories had guided me to a career path I could never have imagined was possible. I wouldn’t have told you at the time that I wanted to someday get paid a full-time salary to create stories about science in new and social media platforms – I didn’t know that was possible.

But as much as stories have guided me in life, it took me a long time to figure out how to tell science stories on paper. Whenever I’d break out my pen (insert: keyboard!) to describe some aspect of science or my own research, my scientific training would kick in – in all the wrong ways. I’d start with the textbook details. I’d use the jargon that I was so familiar with. I’d spend pages “educating” my imaginary audience, catching them up on all the information that I thought they would need to understand my main point or take-home message.

It wasn’t until I started planning to teach a class on Digital Storytelling as a mass communication Ph.D. student that I realized that I had little understanding of HOW to define “story” or teach storytelling to others. Apparently, I’m not alone in this. According to Lisa Cron in her book Wired for Story, we humans have a natural ability to recognize a story when we hear it, but it is harder for us to identify exactly what makes a story a good story. Good stories are a bit like magic – they work precisely because they take us out of our default mode of analyzing and critiquing and ruminating on things. They allow us to suspend our current judgments (according to actress Kristen Bell!), thoughts, mood and even beliefs, and join the storyteller on an epic adventure and see things from their point of view.

It took a lot of reading about storytelling and story structure from some of the greats (like Kurt Vonnegut) for me to begin to better identify what made my favorite stories so good. They had characters, plot, suspense… but most importantly, they had struggle, consequences and insight. They helped me learn something from someone else’s experiences… and how their perspective on things changed as a result.

Of course, being able to identify the important features of a good story doesn’t by default make you a good storyteller. That takes practice!

Writing scripts for our Lifeology “flashcard” courses has been some of the best practice I’ve ever had at storytelling. Lifeology courses or card decks are designed to be ultra-succinct visual narratives that embed scientific and health information in the experiences of relatable characters. Each “flashcard” holds only a “tweet’s worth” or 2-3 lines of text, but the message on each card is carried equally by the accompanying visual. It’s like writing a kid’s book (but often for adults) or a comic – you have to strip out EVERYTHING that doesn’t advance the story, every extraneous science fact or term, because you have so little room to tell the story. I’m now convinced that some of the best storytellers on the planet are children’s book and comic authors and illustrators.

But apart from practice over months and years, how can we become better storytellers TODAY? There are some simple tips and processes that can help. Continue reading for some tips and advice from Misha Gajewski, freelance journalist and senior producer at The Story Collider, and others!

“There are three main elements to a good story,” says Misha. “They are believable, compelling characters experiencing a meaningful event who have to cope with some sort of consequences. When I’m working with other storytellers or crafting my own stories, I always look for a change that took place, whether that was internal or external. In most of our stories at The Story Collider, there is an event where such a change takes place.”

Misha describes what The Story Collider does as more art than it is science communication, even though there is science in all of the stories they tell and promote. Misha wouldn’t interview a scientist for The Story Collider and start with “Tell me about your science…” Rather she helps storytellers dig into the personal, humanities side of science – because science is human, and affects everyone.

If you are having trouble identifying the “consequences” of your story, Misha says to think about the stakes: What could go wrong? Or what could go right? What are you worried about happening?

“The consequences can be as dramatic as life and death. Or they can be as small as sending an e-mail,” Misha said. “But it is all about showing that what is at stake for you in the story is important to you. Whatever matters to you in your story will matter to your audience.”

8 Science Storytelling Tips

1. Distill and simplify. What is this story about, fundamentally? Hopefully the answer to this question is something that any human anywhere can relate to. It could be a story about navigating imposter syndrome and finding your voice, for example. Once you find what your story is fundamentally about, focus all of your scenes, examples and details on advancing that story.

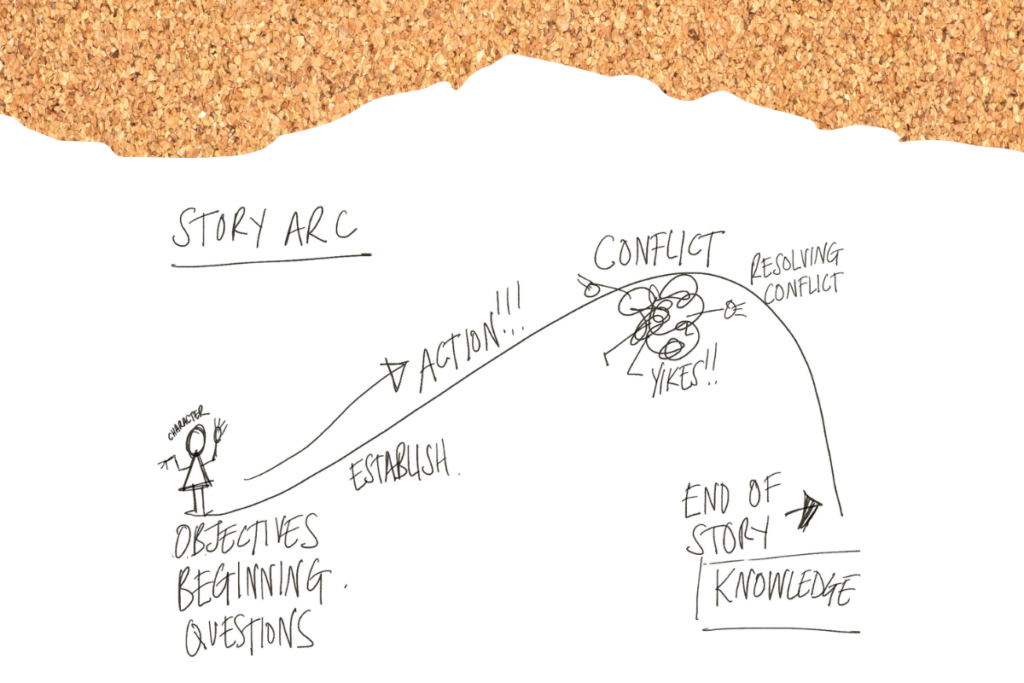

2. Outline your story. Outlining the structure of your story can help you develop a story that is more engaging for your audience, from start to finish. Lifeology artist Matthew Griffiths suggests quickly leading your audience into the “problem” of your story so that they will be invested in following you to the solution.

3. Be honest and authentic with your story. This tip is from Manasi Apte, a science communicator who is currently creating a Lifeology course on Storytelling 101 (launching in early April, 2021!). Honest and authentic stories can be impactful and relatable to all people. For example, sharing stories of personal struggles, failures and winding paths through science can help more people understand that science is a human and thus a relatable endeavor.

4. Take people on a journey, says Manasi Apte. Stories are even more effective when you take the audience on an active journey. So try to make your story an immersive experience for all!

5. Get consent. Are you telling someone else’s story or a story that involves someone else? Stop and take a moment to ask yourself if it’s fair for you to share this aspect of their life. Ask them if it’s ok. Talk to them and have them walk you through this story from their perspective – this conversation will inevitably make your telling of this story better.

6. Think of the science of your story as another character. This tip comes from Misha. “We just need to understand enough about your science character to understand the story and how the science interacts with you in the story,” Misha says. The science character shouldn’t steal the show. It probably shouldn’t be the protagonist, either. The humans (including yourself) involved are likely more central to what the story is really about.

7. Show why you care about the science (character). Talking about why you care about something is far more persuasive than talking about why this something matters in general, Misha says. If you imagine the science in your story as a character, develop the relationship between you and this character in your story. Why do YOU care about your science character?

8. Have visuals. Visuals can help to create an immersive story. (Traditional visuals are great, but if you are using an audio-only format, you could also help your audience to build visuals in their minds with descriptive language and metaphors!) However, it is important that the visuals are easy to understand at a glance and are relatable to your audience. Visuals that communicate human action and emotion are always better than strictly factual aka “cold” science visuals.