Every creative collaboration should have a contract. This is as important for the creative as it is for the patron. The terms in the creative contract decide (among other things) how the work can be used by either party. This topic is very broad and can get complicated, but I want to talk about 3 parts of the contract that I wish I’d known about sooner.

This post is cross-posted with permission. The original article can be found here. This article is not legal advice.

In this Article

- Exclusive vs. Non-exclusive License

- Commercial vs. Non-commercial License

- Derivative Works

- Revising Your Creative Contract

Exclusive vs. Non-exclusive License

When a creative (artist) is hired by a patron (client), the client is exchanging money for a product of some kind. That product is typically a piece of intellectual property owned by the artist. The artist created the product, and thus owns all rights to its use.

When a client hires me to make an animated video for them, the animation I create is my property. That means that I am the only one who can legally use that animation unless otherwise specified in a contract. The creative contract defines when and how my client can use the animation. And one of the first things that should be decided is exclusivity. Let’s talk about what that means.

Let’s say my client wants an animation to use for their lab website. Before preparing the contract, I typically ask questions to better understand what they need. Is the animation specific to their lab? Can I use assets (images, scripts, and animations) from the project in other projects?

If I grant an exclusive license to my client, I am giving them the right to use that work (within reason, we’ll get to that in a moment) for their own purposes. They get exclusive use of the product. That means that I nor anyone else can use the animation.

Why choose non-exclusive licensing for your creative contract?

An exclusive license takes the power out of the artist’s hands, but gives more broad usage to the client. What’s best for the project is up to you both to decide. I’ve done work under both types of license agreements. As shown in the table below, there are pros to both, but exclusivity should be carefully considered for each project.

Pros for each party in an exclusive or non-exclusive license

| Pros for Client | Pros for Artist | |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive License | – Product is unique – May be able to use the product without attribution – Able to use the project for a wider scope (as long as it is within the creative contract’s bounds) |

– Can charge a premium fee |

| Non-exclusive License | – Save money while still getting a beautiful product – Support an artist’s right to their intellectual property |

– Can use some or all of the product for future projects – No questions about using the project for your portfolio – Keep control of your intellectual property and how it is used |

I am often asked “when would a creative want to reuse the project?”, and this is a great question. The most common use (or reuse) of a creative project is as part of the artist’s portfolio. You can certainly create an exclusive license with exceptions for the artist’s portfolio. But there’s another piece to this puzzle.

I work on a lot of projects, and some of them share similar elements. Additionally, some projects I work on for a client while other projects are just for fun. When I hand over exclusive rights to the content I create, I take that exclusivity very seriously. I do not use that work or pieces of that work, and I actually place the working files in an archive with a note that explains the exclusivity agreement of that project. That means when I have another project that uses similar elements, I have to make them from scratch again.

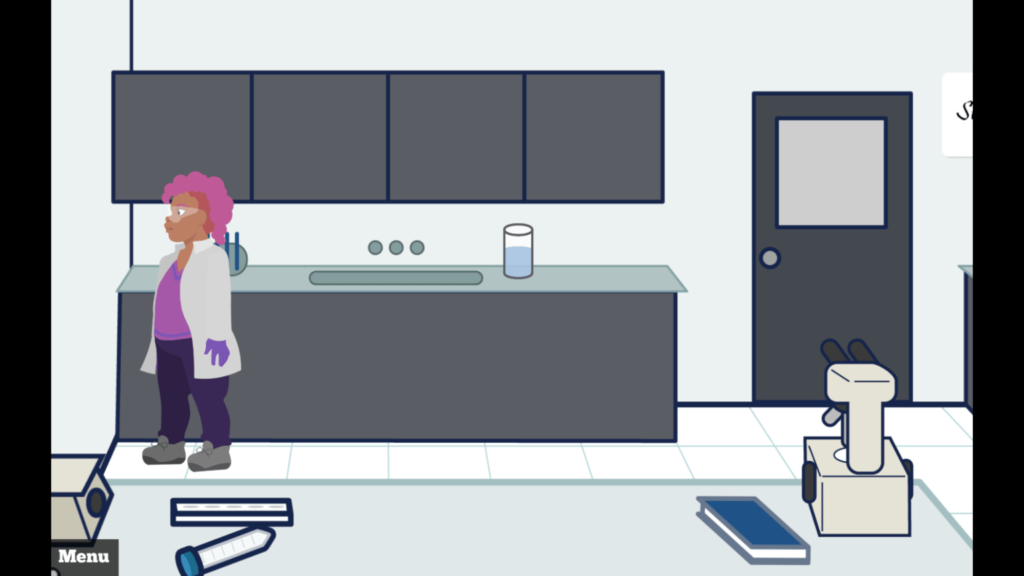

Here’s an example of a reused asset. I was hired to create an animated video for a university department. Part of the video required me to make a lab bench and several lab tools to put on the lab bench. A year later, I started working on my first try at a point-and-click adventure game, which takes place in a lab. Because the project included a non-exclusive license, I was able to use those assets in my game with minimal editing. Importantly, this game was for my own practice and learning purposes, not for a commercial purpose. I typically do not reuse assets for multiple paid projects without heavy editing to make them very distinct.

-

Original lab scene from animated video -

Lab assets used in video game

Commercial vs. Non-commercial License

A client emails me and asks me to create a logo design for them. As usual, I set up a consultation to discuss the project and the client’s needs. During this discussion, I ask “will you be putting the logo on any products to sell? T-shirts, stickers, anything else?” The client tells me that they do plan on monetizing the design at some point in the future.

This will trigger a conversation about the commercial rights within the creative contract. What are commercial rights? These rights tell the client whether they can use the project’s deliverable in things that they sell. In other words, can they make money from my design?

Many creative projects result in the client making money. This can be indirectly, by improving branding or helping to get the message across (leading to better sales or increased funding). Or money is made directly, by selling a product that uses the design in some way. Maybe the project is to create a deck of cards with the logo on the back. Or maybe to sell stickers with the logo on them.

These commercial use cases must be laid out in the contract. As with the exclusive license, allowing a client to make money off of an artist’s work needs careful consideration. Adding commercial use typically increases the price that an artist should charge.

Pros for each party in a commercial or non-commercial license

| Pros for Client | Pros for Artist | |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial License | – Able to monetize the product (within limits of the creative contract) | – Can charge a premium fee – May be able to request a % of sales – May be able to retain acknowledgement rights so that your name/signature is on the project – May have your work seen more broadly |

| Non-commercial License | – If unnecessary, saves money while supporting a creative – Great option for early days of brand |

– No need to worry about others making money off of your labor – No need to regularly contact client to check on sales (if requesting % of sales) |

Commercial contracts can be a monster, but they can also be mutually beneficial to both parties. It’s often best if the client has an idea of how much they think they will make over a certain amount of time ($5000 over the next month, $10000 over the first year, etc), because then you can price accordingly. However, I’ve done quite a few commercial licensed projects where the client didn’t know this. At that point, you just have to work together to find a mutually beneficial solution.

Remember that your creative contract outlines how the client can use the product, and it isn’t bound by doing things a particular way. Feel free to propose creative solutions to find something that works best for both the client and the artist.

Derivative Works

I once worked with a client once who had signed a contract with me to have me produce an animated video. Toward the end of the project, they suddenly asked me to also send them the individual clips from the animation so that they could use them in other projects.

Without a contract, I could have said no or gone back and forth with them until we found a solution. However, because I had a creative contract, I was able to refer to it, which clearly stated that no derivative works were allowed. Doing this made it clear to them that what they were asking for was out of scope and that we would need to renegotiate the contract if they really wanted those clips.

A derivative work is any work that uses and changes the artist’s work after it is delivered. In the above case, the client wanted the ability to edit their own videos, adding in my animated scenes where appropriate. This takes each animated scene out of context, which would make it a derivative work.

Derivative works can be small, innocent changes such as cropping or color enhancement. However, derivative works can also take the intellectual property of the artist and distort it, which can be damaging to the reputation of the artist.

Another project I worked on was creating several art pieces for an event’s program book. After I delivered the final files, they contacted me and asked me if they could have the raw files (ie, the Photoshop or Illustrator file). I sent the raw files to them in good faith, but found out at the event that they had not only cropped and skewed the images, but also had implemented it into their program book layout in a way that made the work seem amateurish. It ruined the flow and composition of the piece.

Any alteration of an art piece after delivery reflects the artist that created it. Best practice is to contact the artist and either have them do the edits for you (with compensation), or have them approve the edits (with compensation). I typically allow NO derivative works in my creative contracts and offer edits for a reduced hourly charge or for a reduced project price if the edits are extensive. This is a courtesy to my clients because I understand that sometimes there’s no getting around edits. However, this is also an important part of presenting my intellectual property to best reflect my skill.

Revising Your Creative Contract

Writing up or reading through a contract may be stressful, but you should never enter a contract without understanding your rights. Clients don’t want to be taken advantage of, and neither do artists. So coming to an agreeable contract is in each party’s best interest.

Don’t forget to add language to your contract that allows it to be changed. The client may want to add items mid-contract, or the scope of the work may change, needing the artist to hire someone to help them. There are a number of reasons why a contract might change, and you should be open to finding the right compromise so that the creative contract fits the project.

Creative contracts are incredibly important for independent creators, first-time patrons, and businesses. They don’t need to be written in the fanciest language possible, just write down the terms you’re agreeing upon as clearly as possible. Make sure to read the contract thoroughly and ask any questions you may have about its contents.

I hope this article was useful for you to learn a bit more about exclusivity, commercial licenses, and derivative works. If you enjoyed this article, you can leave me a coffee-sized tip at my Ko-Fi.