Collaborating across disciplines can be challenging. Different disciplines often have different lingo, processes and even cultures. Sometimes, working with someone from a different discipline can feel like trying to understand a foreign language. (What is “kerning”? Wait, what do you mean by “blue sky project”?)

There are more than a few processes, terms and cultural norms that science communicators and artists use that could be confusing for scientists. Maybe you’ve already experienced some bamboozlement when reaching out to a communicator – a somewhat ironic experience considering the job title!

To help break down these barriers, below are a few things for scientists to keep in mind when collaborating with artists and storytellers. (Note: soon, we will also publish an equivalent post of things for artists and storytellers to keep in mind when working with scientists!)

In storytelling and science communication, messages will come in a different order, quantity and style than you may be accustomed to in science.

When artists and storytellers work with scientists, they are always trying to “find the story” in the research. This is because stories work1,2,3. They capture an audience’s attention, help them to relate to the information and might even help to foster some emotional investment.

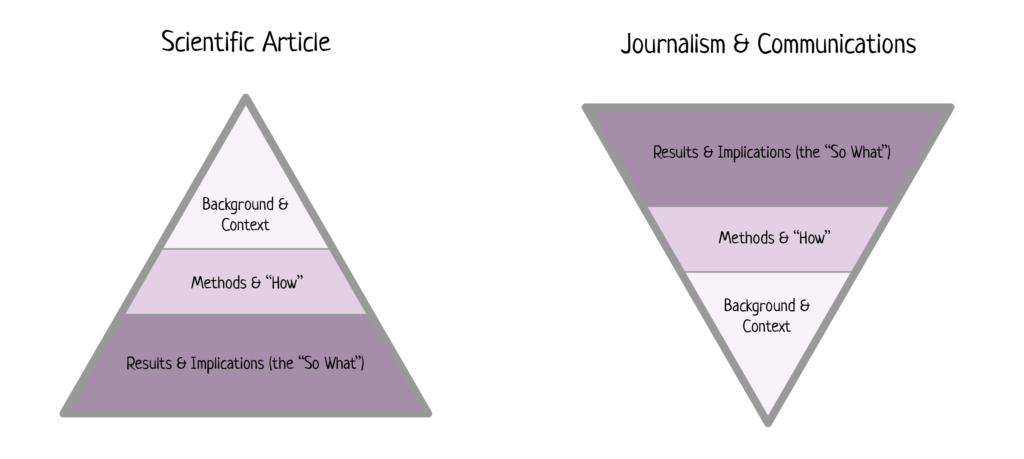

One thing to be prepared for as a scientist is that engaging stories flow differently than scientific articles and traditional scientific posters or talks. A key differentiator between these communication styles that you might already be familiar with is the “inverted pyramid” style of writing used in journalism. In this style of writing flow, the piece begins with the main message or the most important information (in the case of science, the study’s findings and their implications) and incorporates supporting details as it carries on. This structure is the opposite of most scientific articles, which usually begin with supporting details and context and then work towards the study’s findings and implications.

The typical scientific article starts with background details and moves towards the main findings (left), while the typical journalism-style article starts with the main findings and moves towards supporting details (“inverted pyramid”; right). Illustration by Sarah Nason.

It may feel uncomfortable or even frustrating, but letting a science communicator take the lead on the order, structure and style of messages will give you the most bang for your buck. Not only will you get the best work and avoid personal bias, but by embracing the communicator’s ideas and strategies, you will also be able to learn about science communication yourself. If you are open to the process, you can come away from it with some expert knowledge that you can apply to other projects!

To help transition yourself into a different style of writing and communicating, it’s a good idea to give yourself some time to understand why things might be done differently than a traditional scientific approach. When you understand the “why” behind the suggestions and decisions of science communicators, it is much easier to get on board! This informal learning process can include asking questions along the way during a project, chatting and asking questions on the Lifeology Slack, or reading a blog or two to get yourself oriented on some science communication basics. Here are some posts I would recommend!

- Why Should Scientists Work with Artists? by Paige Jarreau

- 9 Tips for Communicating Science to People Who are not Scientists by Marshall Shepherd

- Tips for science communication by Erica Hawkins

- 20 Design Rules you Should Never Break by Mary Stribley

Use of new technology and media formats is not just for “flash”: communicators work with different formats to help you target your key audiences.

Sometimes, I hear frustration from researchers and clients who didn’t grow up with the current reality of rapid technology turnover and trend cycles. “Why does it have to be flashy? Can’t it just be simple?” I admit that communicators sometimes do get ahead of themselves and over-excited about new technologies and techniques! But I wanted to address this sticking point and provide a quick explanation for why communicators gravitate towards these “flashy” techniques.

Communicators want to be sure that your projects meet their goals. For communicators, it all starts with the target audience. Who needs to know your information? What do they know and what do they like? What are their media preferences? When communicators suggest something like using an app or developing a video, they are not trying to substitute style for substance. They are trying to make sure that your science communication project has maximum impact with the people who need to know and use the information you are sharing.

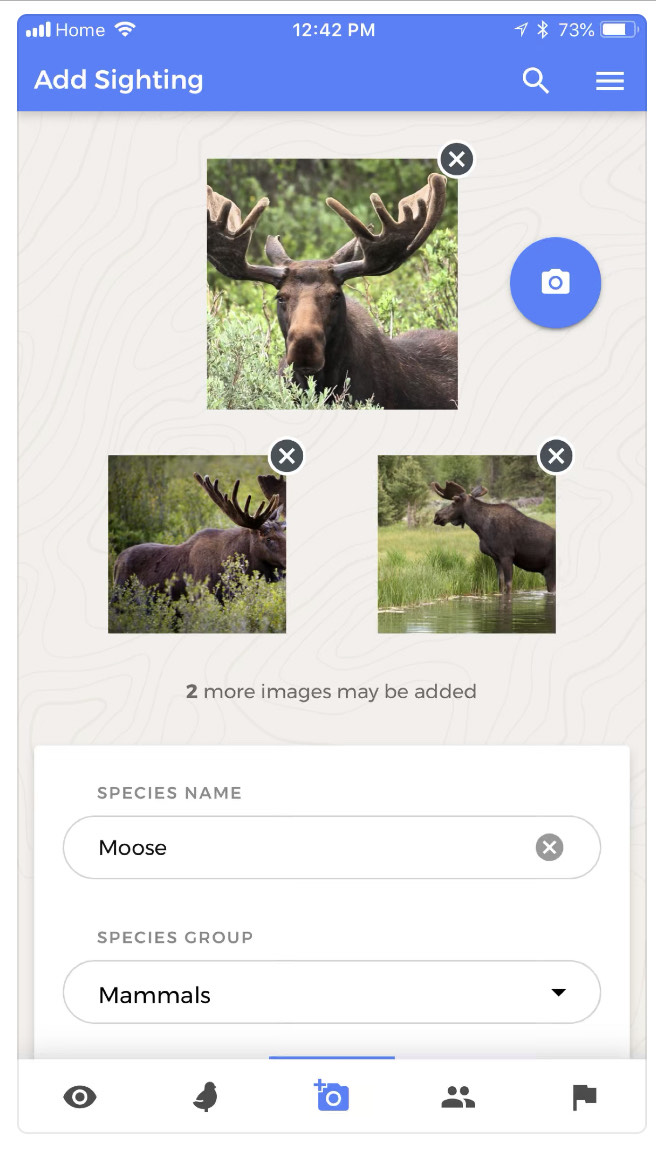

Here is a good example. Apps on mobile devices are becoming increasingly common for engaging members of the public in citizen science projects, such as the collection of ecological data when they are out on nature walks. There are two main advantages to using this technology:

- Many people own smartphones and use them as their primary way to take photos anyways.

- People might be deterred from participating if they needed to complete additional time-consuming steps (e.g., filling out paper forms, returning them to an office).

Apps like NatureLynx (Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute) target their audience by using a format that is accessible for many people and reduces the amount of volunteer work/time investment required to participate.

That all being said, here’s a quick side tip for science communicators: as much as it’s important to cater to the target audience, we also need to keep in mind our clients’ needs and preferences. Technology moves fast and often we are further along the adoption curve than others because it’s our job to pay attention to technology and communications trends. If the scientist you are working with doesn’t want to use an app like Slack or GoToMeeting, it’s important to listen and find a compromise that works for both of you. Sometimes, a simple solution really is best!

Thinking about communications from the start of your research project can help you plan your budget and maximize your impact.

A lot of the time, communications are designed as an end product: once the research is finished, a report, infographic or video is released to explain it. There is nothing wrong with doing just that! However, this paradigm can have the unfortunate effect of limiting and rushing the time dedicated to planning, budgeting and time management of science communication projects.

While working at a science communication consulting firm, I noticed that we would often get contacted and asked to complete projects rapidly in the last few weeks of April because government researchers realized that they had a bit of extra money they could spend on communications before the end of fiscal! When communications projects are not planned or budgeted for and then put through on a rush order, the quality of the final product inevitably suffers.

My advice would be to integrate the concept of science communication and outreach into your research project planning phase. Even if you don’t have much time to flesh out a detailed plan, setting aside a chunk of grant money and scheduling some action items in your calendar can go a long way to making sure that your communications products aren’t created in vain. If you’re in the process of applying for a grant, then budgeting in some arts and communications items is a great idea to put yourself ahead of the game!

Just as science has rules, so too does art and design.

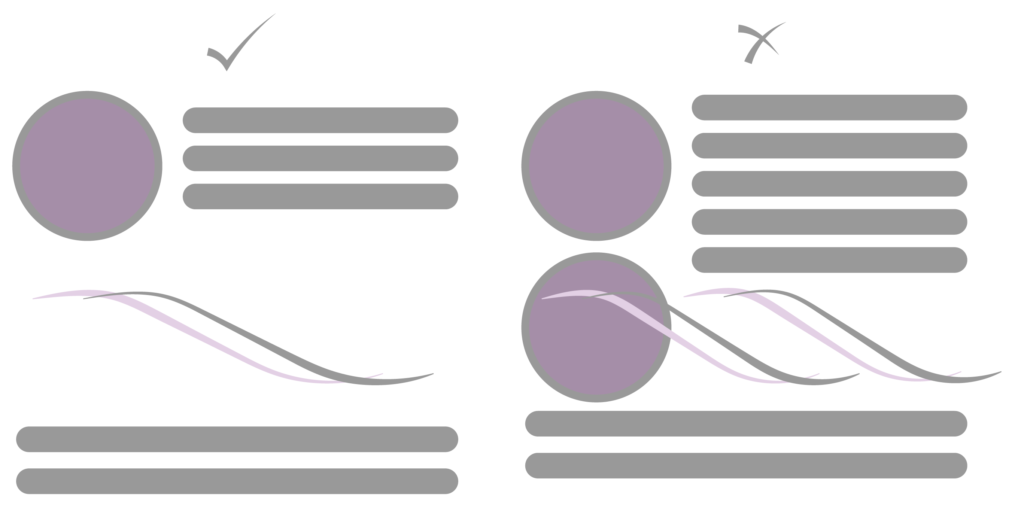

Sometimes, the recommendations that a designer or communicator makes for your project might seem limiting. In my experience, I’ve been in several situations where the preferences of the scientist and the designer or communicator differ, especially when it comes to how much detail there should be in the text or visuals! Scientists and communicators are often at odds on that one, with scientists angling for more detail and precision (think of all the detail in most scientific figures in journal articles) while communicators are striving for more clarity and conciseness.

However, when working with someone from another discipline, it’s important to trust that there’s a reason for their suggestion. Often, they are trying to follow the rules and best practices of their discipline in the hope that it will create a better product. Rather than criticizing the suggestion or pointing out its faults – a gut instinct for many of us, as those are the types of feedback we are often trained to give in academic circles – asking an open-ended question can be a great way to gather some information, enhance your own understanding, and maybe even open up a dialogue for compromise.

Use of white space is one example of a design rule that can improve the visual appearance of a layout, giving elements room to breathe. White space can also make the experience more welcoming for the audience, reducing the intimidation they might feel about the apparent complexity of the information. Illustration by Sarah Nason.

For example, if you’re feeling confused about why a wording choice was made, rather than saying “I think that wording isn’t right,” you could try, “why was that wording chosen?” By starting the conversation with an assumption that the decision was competently made, the collaboration will flow more smoothly. For example, that wording might have been introduced because the target audience is unlikely to be familiar with the more technically correct term.

Personally, I have been on both sides of the fence in these discussions. As someone who started out as a scientist and transitioned into communications later, during that transition I realized that I had a lot to learn about communications and design. My personal advice is that it’s worth it to give each other the benefit of the doubt, and occasionally humble yourself with the reminder that you might have something to learn! In the long run, collaborations based on mutual respect and trust have a way higher chance of succeeding.

Okay, now…how do I get started?

Hopefully this post has given you some idea of what you might experience when working with science communicators, artists and designers! In short, the main things to keep in mind are:

- Storytelling is different from standard scientific writing: Science communicators focus on effective storytelling, which often has a different flow and structure from the writing used in scientific articles.

- Style and substance can work together to elevate a project: Science communicators use diverse formats and technologies to help messages really hit home with target audiences.

- Stay ready so you don’t have to get ready: By planning science communication into your budget and project plan from the outset, you can get ahead of the game and maximize the quality of your scicomm!

- Teamwork makes the dream work: For most scicomm projects, everything starts with effective collaboration between scientists and science communicators. Show mutual respect for each other’s disciplines and be prepared to learn from each other.

If you’ve got some questions before you embark on a scicomm collaboration, check out the Lifeology Slack! The platform is chock’o’block full of scientists, science communicators, artists and storytellers who have loads of experience and can lend you a hand. Or, if you are ready to reach out to a science communicator to collaborate, the Lifeology member directory is a great place to start browsing for a connection to help launch your next scicomm project.

Happy scicomming everyone! :)