Art has at least seven different functions, according to Alain de Botton and John Armstrong’s “Art as Therapy”: 1) Remembering, 2) Hope, 3) Sorrow, 4) Rebalancing, 5) Self-Understanding, 6) Growth, and 7) Appreciation.

Art helps us to remember the past, hope for something better and process our feelings. Last year, before hearing about this book, I wrote a blog post called “Stages of Grief”, which speaks directly to the third function of art above. Today, I would like to focus on the second function – Hope. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, hope is definitely something we need now.

“Art helps us to remember the past, hope for something better and process our feelings.”

Throughout my life, I have always been very cautious about getting carried away by hope. It felt safer not to get my hopes up before something was known for certain, in order not to feel disappointed later. When I was in college, my favorite quote was “A cynic is in idealist, whose rose-colored glasses have been removed, snapped into two and stomped into the ground, immediately improving his vision”. I used it as a form of self-defense.

But in the current climate, the other side of self-defense may be more relevant – remaining optimistic in the midst of crisis. During hard times, we need to remember the good and maybe even put our rose-colored glasses back on, so we can focus on the beauty of this world.

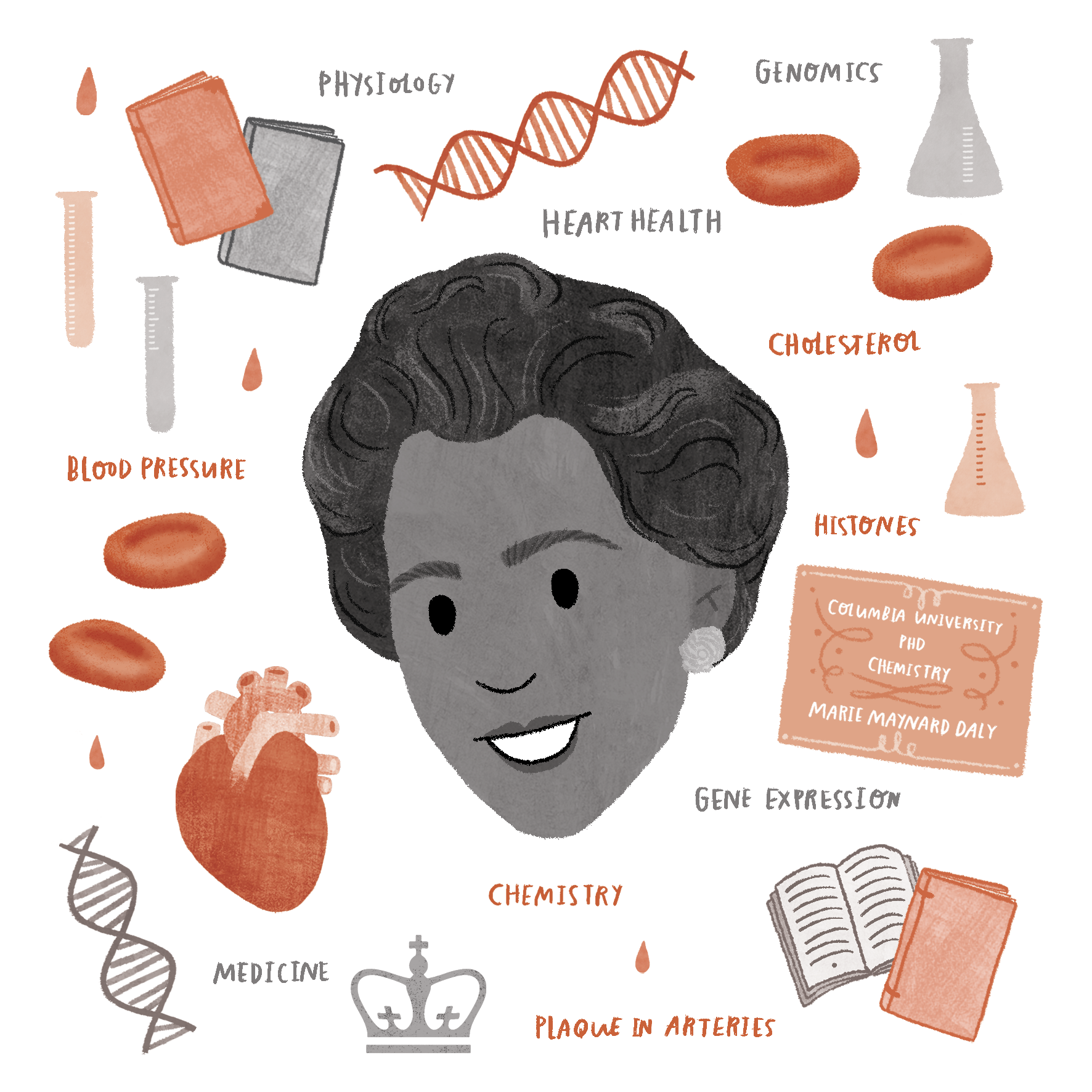

How the “Hope” series was born

While making the “Stages of Grief” series, I made a sculpture of a large hourglass filled with black sand with a human eye on the bottom. The black sand symbolizes the bad news and emotions that bombard us daily. Reflecting back on this sculpture now, it feels particularly relevant as we continuously follow the news of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, inside of the eye I placed a white crystal that would symbolize Hope, which consequently became the name of the sculpture. This white crystal inspired me to create a whole series around the topic of hope, placing this symbol into each of the works. In this original “Hope” sculpture, I intentionally placed the crystal slightly out of field of view to show that hope does not always appear in an obvious place. You need to put in some effort to find it within yourself.

Sense of isolation

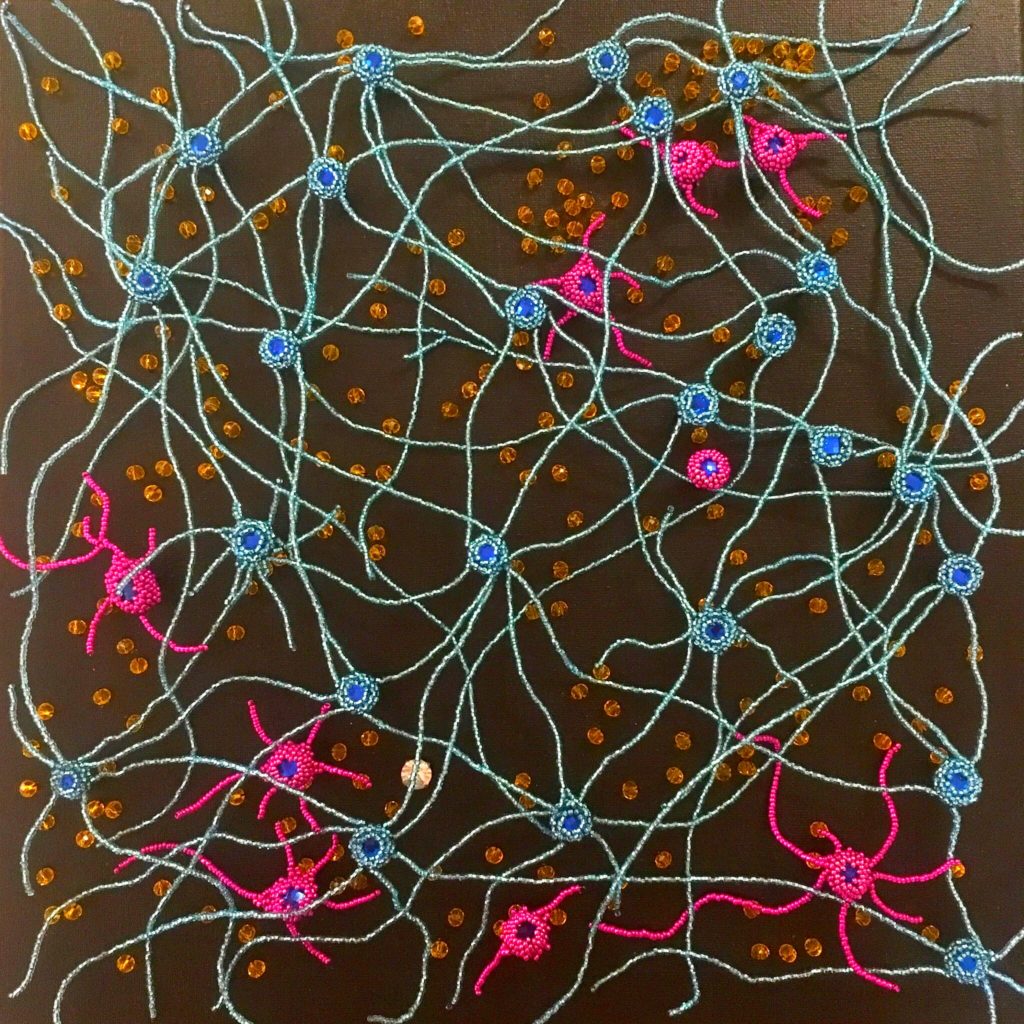

Following up on this theme, I proceeded to create “Lost in Manhattan”, which is based on an image of stem cell-derived cortical neurons that I took in the lab. At the time, I was going through a transition, where I felt like I was losing a part of my identity. I decided to portray the idea of a thick network, representing the complex composition of a large city. The dense neuronal connections would portray the jungle gym that we need to maneuver in both a large city and life in general. I wanted them to be very tangled and interdependent, but elegant at the same time.

Placing a small white crystal off to the side and underneath one of the axons, I wanted to show how oftentimes we can feel lonely, isolated and disoriented despite being in the center of a large city. Again, this concept took on a whole new meaning in the time of social distancing. Nevertheless, it can still represent a spark of optimism we can find in ourselves regardless of external circumstances.

Striving forward and self reflection

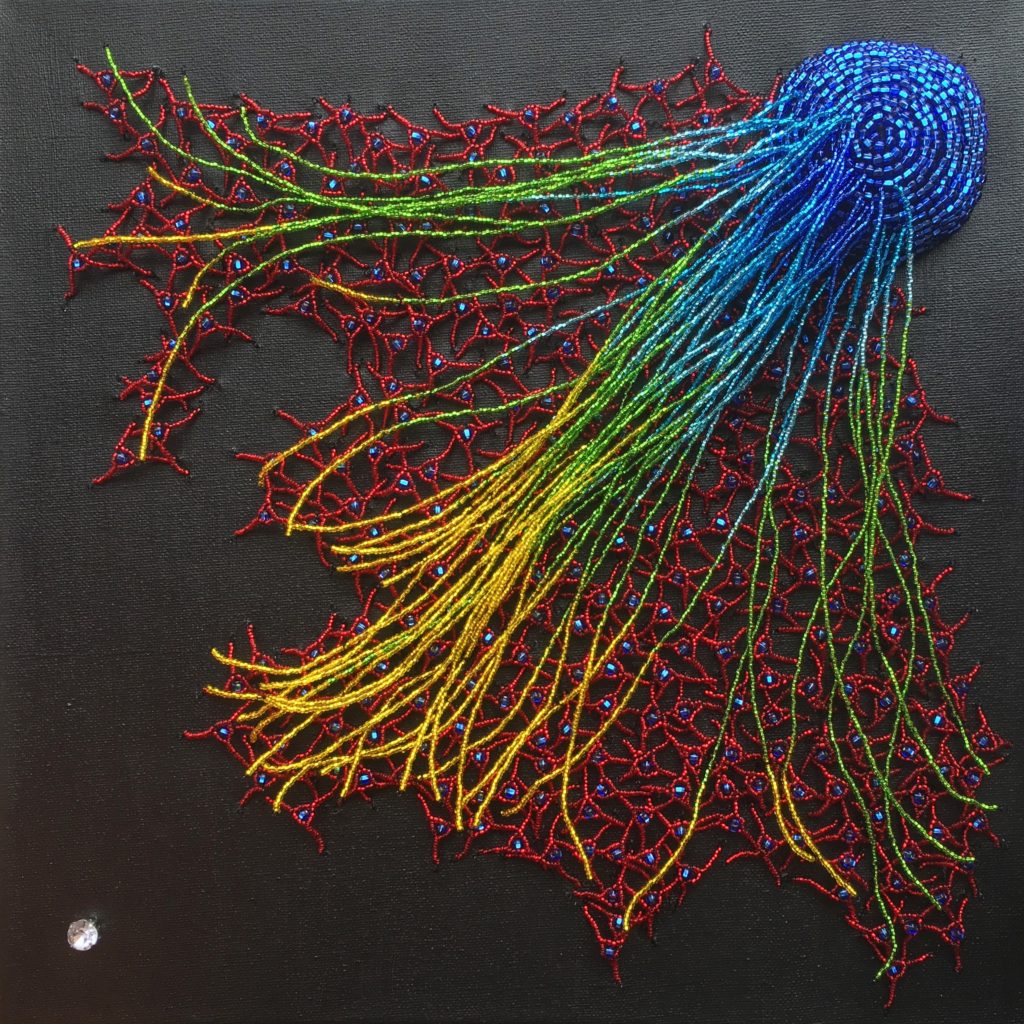

“Attraction” comes from an image of a stem cell culture that started as a neurosphere (blue) and is gradually generating a flat, uniform lawn of astrocytes [a type of cell in the nervous system and brain] (red), paving the way for the neurons (light blue to yellow). As the neurons extend away from the neurosphere, they go through a transition of differentiation markers, creating a color gradient.

I had bookmarked the original image a long time ago, but started making it only when I could put it into the context of this series. Given how the cells migrate away from the neurosphere, I wanted to show that they actually move towards a new target, shown as a crystal, hence the name “Attraction”.

Pushing forward and away from the state of feeling “lost”, we set a new target and strive towards something better. And this process takes a lot of patience and effort.

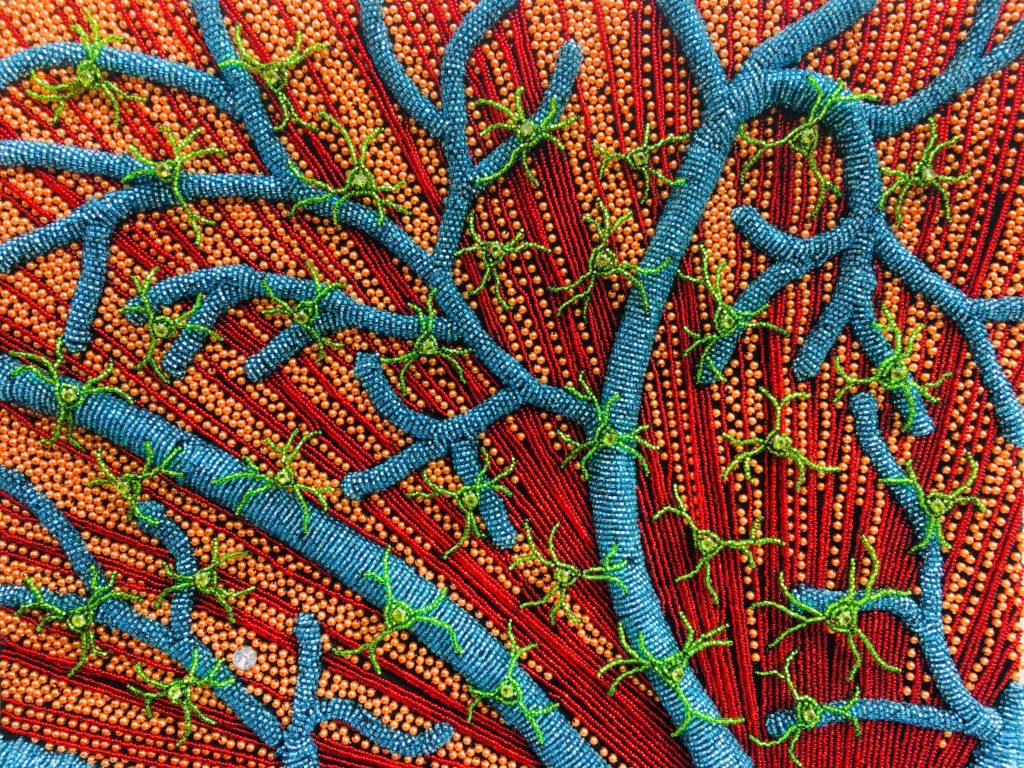

In addition to setting your mind on a new goal, making a change often takes some self-reflection. It can be quite difficult to distance yourself from your emotions and take an objective look at the situation at hand. To portray this idea, I found the metaphor of an eye to be quite useful once again. However, while in “Hope” we view the eye as it faces the outside world, in “Finding Your Self” I used an image of an eye retina, which is located in the back of the eye and is responsible for our sense of vision.

This was my first work that is based on an image of whole tissue, rather than individual cells cultured in a dish. It includes blood vessels (blue), neurons (red) and glia (orange and green), emphasizing the complexity that exists within us.

As I was creating this piece, I thought about how we view ourselves versus how we view the outside world.

Our retinas have a small area that contains no photoreceptor cells and does not receive any information, thereby creating a “blind spot“. The blind spot is located where the neuronal axons converge and exit the eye to transmit information to the brain.

When it comes to self-reflection, we are often blind to both our beauty and our flaws, our strengths and our weaknesses. Anatomically, the missing information is compensated due to the fact that our two eyes are “blind” to different areas in our field of view, creating the ironic scenario that we are not even aware of our blind spots. The same is true metaphorically – we do not realize what we are missing in viewing ourselves. But if we dig a little deeper, we can find the jewel of hope very close to the part of ourselves that we have been ignoring, and see ourselves in a new light.

Remembering the good

“Art helps us accomplish a task that is of central importance in our lives: to hold on to things we love when they are gone.”

“Art is a way of preserving experiences, of which there are many transient and beautiful examples, and that we need help containing.”

– Alain de Botton

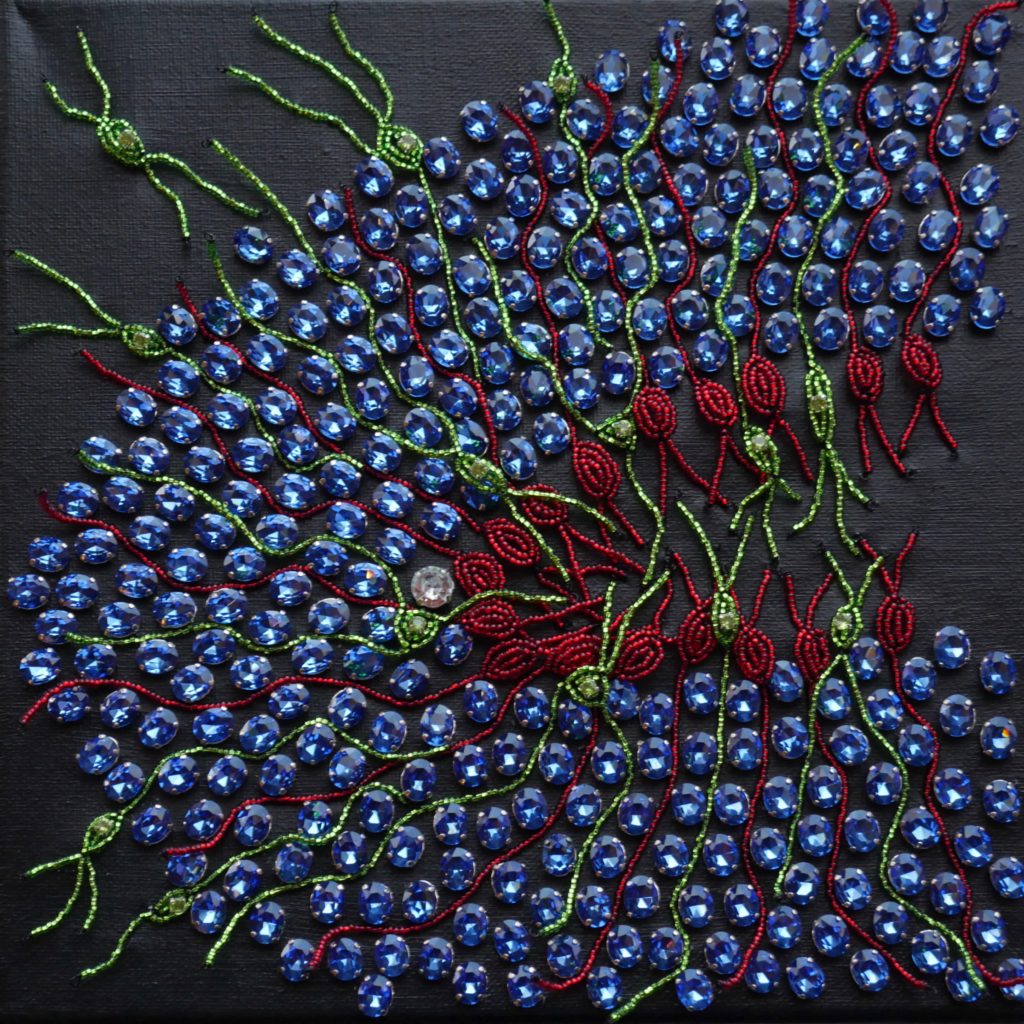

Another way of battling stress is focusing on happy memories. Memories are formed and processed by a part of the brain called the hippocampus. Just like the rest of the brain, the hippocampus is a very complex structure.

In order to delineate the brain’s intricate network of connections, scientists created a genetically engineered “Brainbow” mouse strain. These mice have brains that are bursting with dozens of colors, making it easier to trace individual neurons.

While it has long been believed that formation of memory progresses from learning to long-term storage to retrieval, over the last decade it has become evident that every time a memory is recalled it becomes labile. This is a double edged sword. On the one hand, it allows us to continue learning and updating our understanding of the world as we acquire new information. On the other hand, each time a given memory is recalled, it becomes unstable, at the risk of being inaccurately modified or possibly even lost.

Based on this research, I have created “Fragile Memory”. It shows the delightful confetti that is observed in the hippocampus of the Brainbow mouse, emphasizing the complexity of memory storage and retrieval. The white jewel in this work represents a memory of a good time in our life that we would like to keep revisiting yet be able to preserve.

- “Fragile Memory”, 2019

“Deep Within” is also based on an image of the hippocampus, but this time it is a closeup. Beyond processing memories, the hippocampus also plays an important role in spatial navigation and contextual learning. What is even more amazing is that the hippocampus is one of very few areas of the brain where new neurons continue to be born during adult life. This process allows us to form new memories and modify old ones, as well as process stress.

Both physical activity and certain common antidepressants reduce depression in part by promoting the process of hippocampal neurogenesis [birth of new neurons], making it a very important area of research for mental health disorders. In “Deep Within”, the newly born neurons (in green) are shown as they migrate through the dentate gyrus, and differentiate to form new connections. Given its relevance to our emotional well-being, this work also received a white jewel to represent optimism and became a part of the “Hope” series.

Over the course of art history, there has been a lot of debate about whether art is a frivolous luxury or if it should serve a more serious purpose. Pretty art, such as for example a painting of colorful flowers, has been criticized as a way of idealizing the world by stripping away and ignoring the disturbing reality. Instead, the critics argue, art should be used as a way to attract attention to what is wrong in the world and serve as a conduit for change.

However, we need to be able to choose the right time for each of these approaches. Balancing reality and optimism is essential for our mental health and in times like these, during the COVID-19 pandemic, we need to be able to take a moment and use art as a respite from our daily struggles. At a time like this,

“Cheerfulness is an achievement, and hope is something to celebrate.”

– Alain de Botton