Trophy hunting is a controversial topic in animal conservation…

This form of hunting is done for sport rather than food and the aim is to obtain a ‘trophy’ of some sort, whether it be tusks, horns or a taxidermied head. Arguments about it flare up every so often, and they usually degenerate into name-calling and mud-slinging very quickly.

This reared its head again in July, in response to an article about UK ministers delaying their plans to ban trophy imports. On one side were animal rights and welfare activists who think that killing an animal is wrong under any circumstances. On the other are conservationists who may not like the industry, but think that without viable alternatives outright bans will be harmful for wildlife and possibly accelerate extinctions.

Whilst trophy hunting technically includes deer stalking in Scotland, or shooting a bear in the USA, it generally refers to the hunting of wildlife in southern and eastern Africa. Huge tracts of land are dedicated to this industry. In sub-Saharan African countries where it is permitted, areas used for hunting exceed the size of other protected areas by almost 25%.

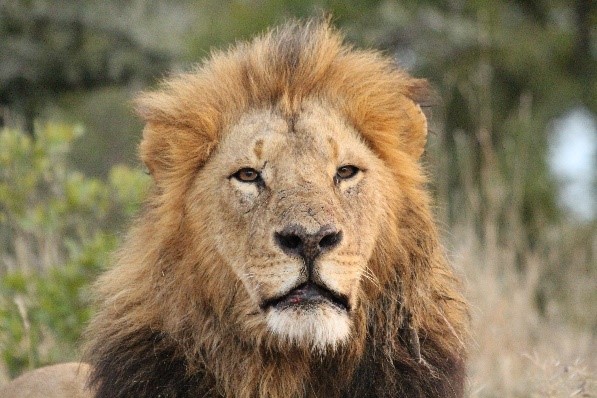

Lion in the wild. Photo credit: Nick Harvey

Trophy hunters spend huge amounts of money to visit places that are often not frequented by other tourists. It is inarguable that the money allows large areas of land with low human population density to support big wildlife populations and it is likely that a lot of hunters would take their business elsewhere if they could not take their trophies home. Banning imports of trophies could cause this industry to implode, and there is no guarantee at all that the land would be put to use to support healthy wildlife populations.

This topic is emotive on both sides. For animal rights activists, knowingly killing these animals is unforgivable. For conservationists, decreasing extinction risk is the primary goal. In addition, telling Africans what to do with their wildlife can easily be interpreted as an expression of a colonial mindset that is paternalistic, patronising and unacceptable.

“Telling Africans what to do with their wildlife can be easily be interpreted as an expression of a colonial mindset that is paternalistic, patronising and unacceptable.” – Nick Harvey, PhD candidate

A lot of these arguments happen without reference to – or consultation with – the people who actually live with the wildlife that is being discussed, people who are perfectly capable of speaking for themselves.

A group of them did just that by writing an open letter, addressed to some UK celebrities who have been outspoken in their opposition to trophy hunting. Around 50 community leaders from Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe said that the romanticized view of elephants, lions and other wildlife gets in the way of them being able to manage them pragmatically.

With such high emotions, the argument can quickly become a race to the bottom. Scientists have been accused of being shills for the trophy hunting industry. The actor Peter Egan even suggested that supporting trophy hunting was “analogous with supporting Jimmy Saville’s access to NHS trusts because he was raising needed funds”. When debate on a topic becomes hysterical so quickly, it can be difficult to communicate its nuances. This is often the case in conservation, especially when it comes to keeping animals in captivity or killing them.

Science journalism is crying out for detailed and balanced reporting on these topics, and there are some things that could help to achieve this. Firstly, it must be remembered that conservation and animal welfare are not the same thing. Their aims often overlap, but not always. Animal welfare concentrates on individuals, whereas conservation is more concerned with populations and species. As such, individuals can be killed if it will reduce extinction risk for the population or for different species. People often get the two confused, which makes real debate difficult.

Secondly, it is very easy to discuss wildlife without even mentioning the people who live alongside the species in question. Species such as elephants and lions are dangerous, and they can cause real danger to lives and livelihoods. It is hard to understand that unless you experience it.

Marauding elephants destroy local crops. Photo credit: Nehanda Radio

Professing to care for animals is certainly noble, but it can easily be interpreted as valuing them above humans. These sentiments can also slide into neo-colonialism, where it is assumed that the person speaking knows what is good for these communities better than they do themselves. Wildlife and nature are certainly global heritage, but telling other people and countries what they should do with the nature on their own land is not a good look.

Finally, communicators need to take a holistic view of these things. In isolation, killing a mouse seems cruel and unnecessary. But what about killing a mouse that is invasive on an oceanic island and eats albatross chicks alive? That becomes a different story.

Albatross chick. Photo credit: Noah Kahn/USFWS

Ultimately, whether or not someone supports an intervention such as culling an invasive species comes down to their values. Will they tolerate killing some animals to save others, or is killing so fundamentally wrong to them that it will never be acceptable? These values are hard to change, and hurling insults is certainly not the way to do it. Sometimes the best we can do is present the situation as it is, be inclusive of voices that are normally suppressed, and let people make up their own minds.