Those of us who have written (and read) summaries of scientific papers will know that there are a few ways of creating these summaries.

When I was an editor at Nature Reviews, we would write very short (100 words or so) In Brief summaries of research papers, or longer and more detailed Research Highlights, both for academics.

Many of us write blog posts, which are usually more casual and tailored to a lay audience.

The journalists among us may write more news-like type articles summarizing the key findings of a paper.

But have you ever thought about writing a poem to bring a research paper to life??

In my poetry workshop, we recently experimented with a form of poetry called “Found Poetry”, which can be a fun and engaging way of conveying scientific ideas. And an interesting challenge for science communicators!

What is Found Poetry?

Found Poetry is basically the literary equivalent of a collage; it’s a form that involves using the words of an existing piece of work and re-arranging them to form a poem. The new “found” poem can either simply play on the original piece of work with line breaks and changes in punctuation (called “untreated”) or it take it to a new place and give it new dimensions and meanings (called “treated“).

Typically, sources would be another poem or literary piece of work, although poets have played with anything from recipe books to appliance instructions to ads – so why not scientific papers?

Ok, so what do I do?

First, you need to pick a piece of work that you want to work on. For science communication, this could be a paper (primary or review) that you want to play with – although posters and infographics are valid, too. Ideally, pick something that you are interested in or passionate about.

I have been increasingly fascinated with the vagus nerve, its connection to mental health and immunity, and the potential to regulate it through yoga – so I picked a review article on this topic!

Next, you need to find the words or phrases that you will use for your poem. This is where it will get a bit tricky – scientific papers don’t have beautiful language, in fact they are full or technical, jargony words that you would normally adapt or translate in a piece of science communication (case in point in my paper, abdomen and gastrointestinal tract verus belly or tummy).

But, sorry, this isn’t allowed here! You have to work with the words in front of you, so you need to be creative and see the potential in those more challenging words (including any double-meaning or colloquial uses). It might help to have an idea of what you want the poem to be about, or what its key message is, and whether you are following the same kind of structure as the paper.

For my piece, I challenged myself to just use the abstract. It proved an impossible task, so I allowed myself to look through the first section of the review as well. You have the freedom to use the whole paper, but I think it helps to limit yourself a bit, otherwise you get lost in the words and may find it difficult to pick them.

Now, start putting it all together. You may find that you want to go back and look for additional words because the ones you picked don’t make a poem – that’s fine. As long as you stick to just using the words in your paper, you are still writing a found poem.

Bonus: Although purists may object to this, many poets add 1–2 more words that are not in the original source. Choose those wisely!

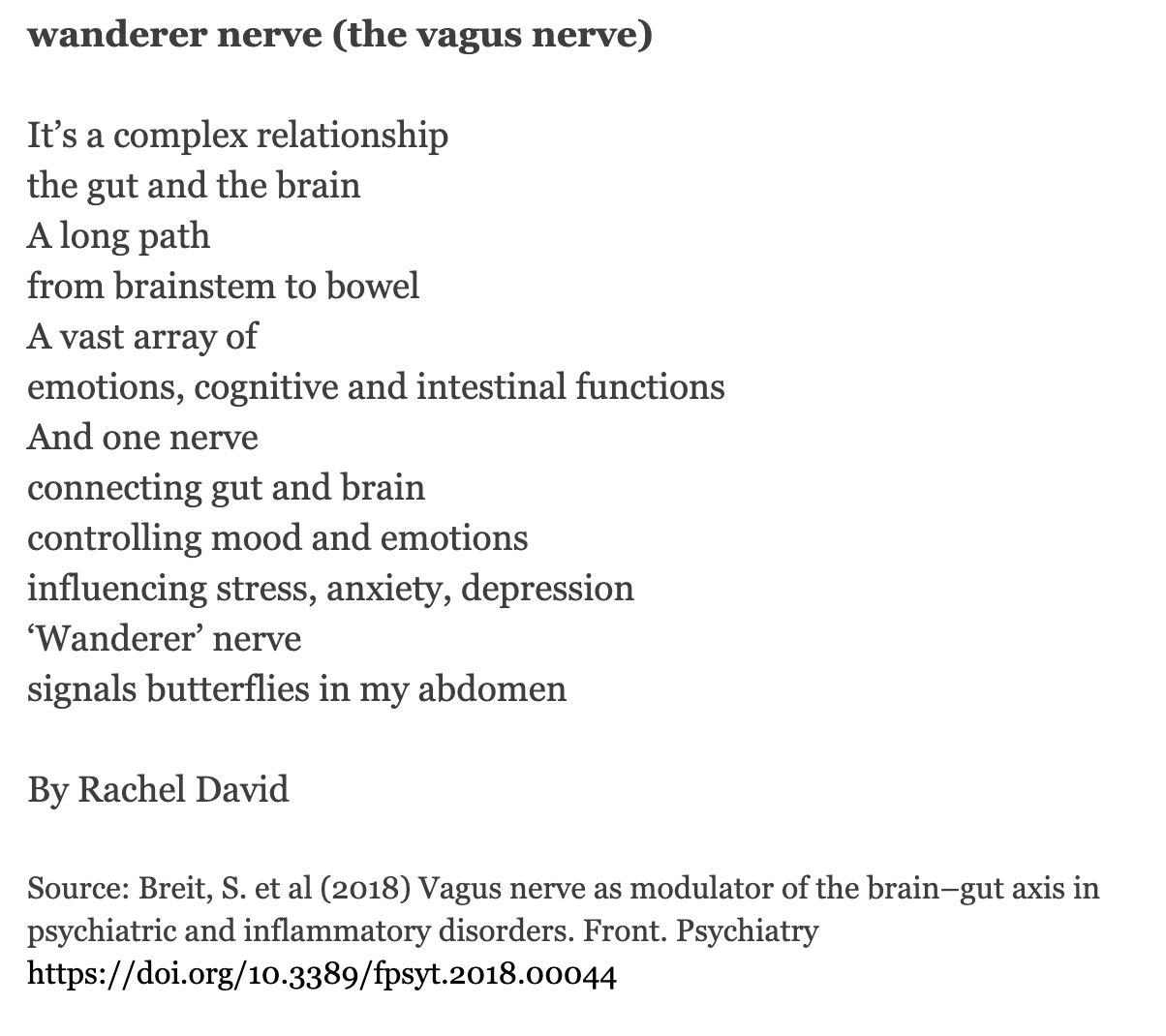

And this is what you get…

I wanted to very simply tell the story of the vagus nerve and its fascinating role as part of the gut–brain axis, so this formed the foundation of my poem. I decided to keep it short and simple, using some of the technical language in the paper but then ending with my bonus word to make it more human.

Now, granted, this isn’t my best piece of work, but from the comments of my fellow poets in my workshops, I think it achieved what it set out to achieve – convey the wonder of the human body!

It turns out, people are interested in science, you just need to talk about in the right way.

What do you think? Will you give Found Poetry a go?