We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

Simplify

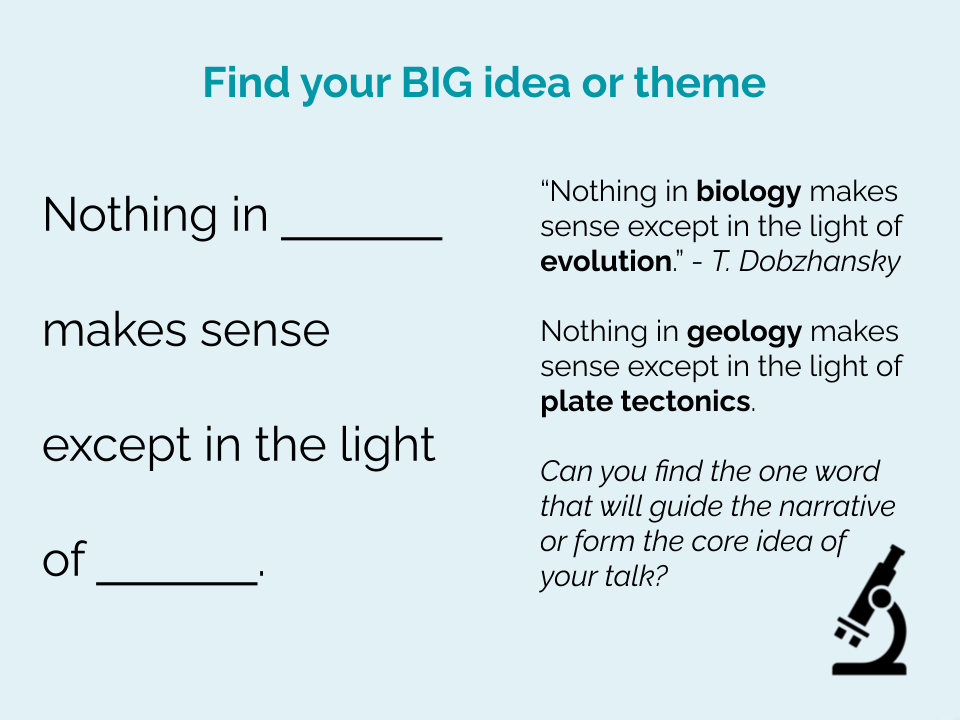

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!].”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection.” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling. We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story, using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story, Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters, although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict, although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change. Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

Visuals

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard.

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!