I recently had the opportunity to write a Lifeology course about stress and resilience for correctional workers. The goal was to create a resource that correctional workers could see themselves in and also benefit from in terms of mental wellness. But my biggest hurdle in writing this course was that I knew very little about the experiences of the intended audience, but I only had two weeks to learn more and write the course.

It’s one thing to research and summarize factual information about stress in the correctional system for employees, and another to be able to frame this information into a story that reflects the lived experiences of those employees. But the latter is the better way of creating a resource that makes a difference in people’s lives. Stories are not only more understandable and memorable than summaries of information, but they also have the unique potential to change people’s minds, beliefs and behaviors.

But to write an inspirational story, you have to really know your characters (aka your readers). You have to know where they are starting from, what their days look like, what struggles they face, and what would motivate them to do things differently. You have to know your characters in order to write stories about the inner changes they go through that your readers can relate to and be inspired by. (Check out Lisa Cron’s books and resources to learn more about why inner change is the crux of good storytelling).

I know nothing about correctional work except for what I’ve seen on Netflix series set in prison – which is to say I know absolutely nothing (potentially less than nothing if I’ve encountered misinformation or stereotypes about correctional work). I’ve never known someone who works in the correctional system, nor have I had a much experience with PTSD other than seeing people close to me deal with trauma and grief. So how do I write a story about a correctional officer coping with PTSD and work-related stress, burnout and depression, in order to help readers see a path toward better mental health and resilience for themselves? Is that even the right story to tell? And if so, how do I tell that story while making sure not to reinforce any bias, stereotypes, injustice, mistreatment or dehumanization inside the correctional system? How do I tell this story empathetically and ethically?

You might already see where I’m going with this – you can’t tell an inspirational story of inner change in your character (aka reader!) without knowing about their experiences and relating to them. So how do you do that?

There are many ways to get to know your audience (or story character). If you already have a relationship with them, open conversations are the ideal place to start! But what if you don’t already have access to members of your desired audience or community? Or what if you could but it would take time that you don’t necessarily have on deadline? (Although for some stories, I’d argue that the deadline doesn’t matter, you can’t tell the story until you DO talk to the audience).

Below are 5 tips for getting inside the mind of your audience to learn more about their concerns, experiences, beliefs, misbeliefs, questions, struggles, wants, needs and desires. Knowing these things will help you write a more compelling, authentic story!

Who is the main character (read: your audience, or the hero) in your science story? Who are they? What do their days look like? What are their hobbies or passions? What are their concerns or fears?

1. Start with online research.

Based on what little I know about the mental health needs of correctional officers from a prospective partner I was writing this story for, I started by going by Googling everything I could on correctional officer stress, burnout, roles, work experiences and mental health. This included searching Google Scholar for research and case studies on these topics, as well as searching news media articles, blog posts or any first-hand accounts I could find. This provided a ton of great information to start from in terms of learning more about the character I would write about.

Online research can provide a lot of information about who your audience is, what they do and what communication strategies or interventions have worked to reach them in the past based on research studies.

2. Find first-hand accounts, stories or quotes.

Your audience may already be sharing their own stories and experiences online in the form of social media posts or media interviews. This is a great place to start if you don’t necessarily know any individual audience members personally in order to talk to them and ask them questions.

In my research for the correctional work and mental health Lifeology course, I found this fantastic Guardian article that includes interviews with several correctional officers about their experiences with work-related stress, trauma and PTSD. This helped me learn about the culture among correctional officers and some of the work-related stressors they commonly deal with. I incorporated this into the character I created for the correctional work mental health Lifeology course. I even used some quotes from this article.

3. Does your audience have common questions or concerns you can learn more about from their online activity?

Perhaps members of your intended audience have posted questions to Quora, participated in published Q&As or produced other online content that gives you clues about what their questions or concerns might be related to your story topic. Reading content like this can help you get inside of your audience’s mind and begin to empathize with them.

4. Find underlying truths or common experiences for your audience that you can relate to.

Empathy is critical to effective storytelling. Rather than coming at your research from a judgemental an analytical perspective, try to stay curious and open-minded. How might you feel if you were in your audience’s shoes and experiencing their daily to-dos and struggles? How might you react to others telling you what to do and how to deal with your struggles? What natural negative or positive reactions might you have? Try to consider all of these when writing the story of your character’s journey and ultimately their inner change. How can you help your character (and thus your reader/audience) be the hero of their own story, journey or inner change?

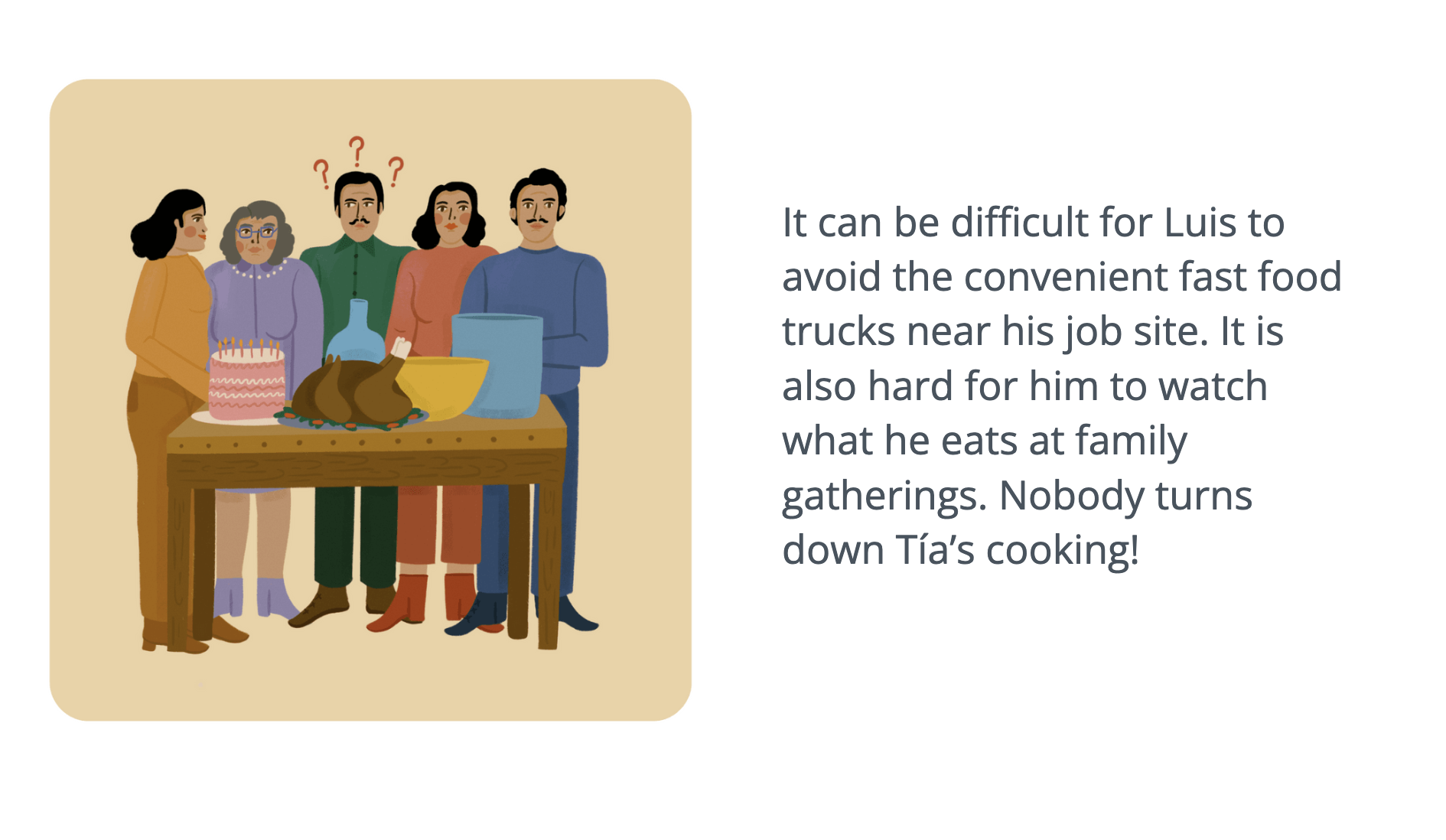

I wrote a story about a correctional officer facing work-related stress and trauma, dealing with the aftermath of this stress in ways toxic to his own physical and mental health, and coming to a realization that he needs help and self-care. This change is not easy for anyone to realize, but it is especially difficult from within the conservative and male-dominated culture and norms of correctional work. In writing this story, I had to critically consider my own biases and emotions as well as the beliefs and experiences of correctional officers. But how could I empathize with my character when I don’t experience anything close to what he would experience in my story? One approach would be to strip the story down to fundamental human truths and struggles.

We all turn to behaviors that make us feel good in the moment even if they hurt us in the end (like dealing with stress by drinking, or avoiding our problems). We all struggle to admit when we need help. I could think about times when these have been issues for me, and then think about how I might feel or what I might need in order to make a change. While the details would be different for me than for a correctional officer, of course, empathizing with these underlying truths while leaning on research about my audience could help me write an impactful story.

5. Find reviewers.

If you aren’t able to talk directly to members of your target audience before you start writing a story, it is critical that you at least get their input as you put together a draft. It’s amazing how effective social media can be in this regard. I had no idea where to start in terms of finding reviewers for my Lifeology course on the mental health and resilience in correctional work. But all it took was one tweet to have a colleague message me that she had recently met someone who did criminal justice research and worked with correctional officers. Within 24-hours of that tweet, I had a draft of my story in front of an expert in this area who provided fantastic feedback on my story that helped me better capture the lived experience of correctional officers on the job and at home.

Try to find reviewers who are experts on your topic, who are community leaders within your audience’s community, who regularly work with your audience or who directly represent your audience. Their feedback will be invaluable! Make sure to involve them early enough that you can incorporate and feedback they provide and re-write your story if necessary.

Of course, there is nothing more valuable than building personal relationships and being able to ask questions and actively listen to members of your audience! Whenever possible, this should be the first step to writing a story featuring characters who represent your readers.

Finally, be open to feedback when your story gets published and people read it in the wild. If you get good feedback from your audience, akin to the idea that your story really “got” them, you know you did a great job! If they tell you otherwise, be open to going back to the drawing board.