People in STEAM (science, tech, engineering, arts, and math) are blazing trails—both people from history and in the world today. We want more people to know about these people and their excellent but often under-promoted work, including children (and adults!) who might dream of careers in STEAM fields!

Each month, we feature a new person from history in our Historic STEAM Heroes Lifeology card deck. These people often faced adversity and overcame obstacles to become the STEAM heroes that they are today!

Is there someone from history that you would like to nominate? Help us curate examples of historic steam heroes from around the world—not just Western culture. You can nominate here.

Keep reading to learn about the woman featured for the month of April!

Barbara McClintock is featured in our Historic STEAM Heroes course.

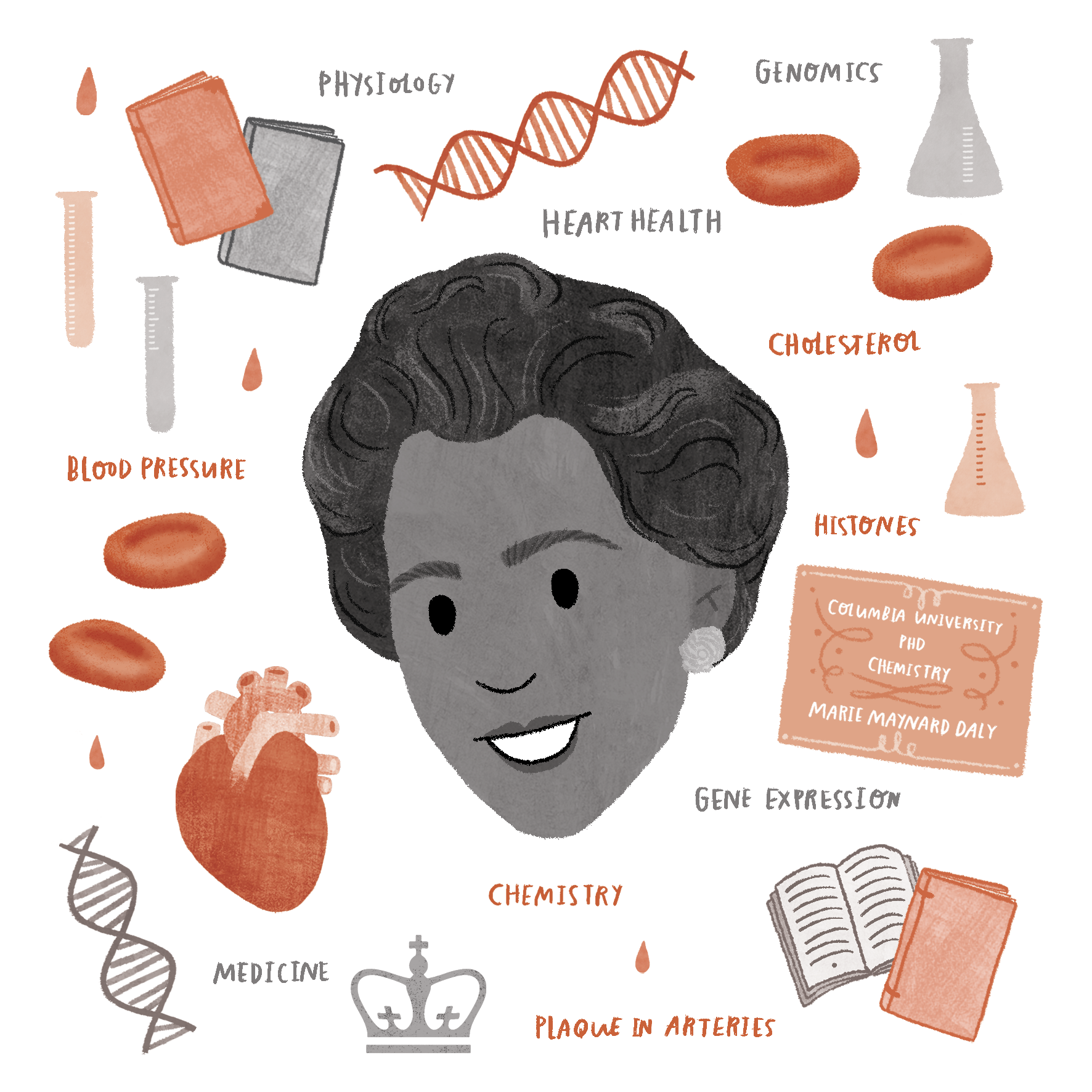

Barbara McClintock was an American geneticist who most famously studied the cytogenetics of maize. She challenged the idea that genes were stationary. Instead, she discovered some genes could move around. Her work earned her the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. As of 2022, she remains the only (and first!) woman to receive an unshared Nobel Prize in the category.

“If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off…no matter what they say…” –Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock, Ph.D.

June 16, 1902 Connecticut, US to September 2, 1992 New York, US

McClintock was born in Connecticut. Her family moved to New York early in her childhood. In high school, McClintock discovered a love for science and wanted to further her studies. McClintock’s mother found the idea of pursuing higher education a sure way of making McClintock “unmarriable.” However, McClintock’s father was supportive of her desire to go to college.

McClintock attended Cornell University during a time when women couldn’t major in genetics at Cornell, so she studied botany. She earned a B.S. and an M.S. degree before remaining there to earn her Ph.D. in 1927. While there, she still pursued genetics. She took the only undergraduate-level genetics course offered. That professor then invited her to take a graduate-level genetics course while she was still an undergraduate.

After her Ph.D., McClintock pursued genetic research at several institutions through prestigious postdoctoral fellowships. McClintock focused on the cytogenetics of maize. She examined the breeding of maize plants and the mutations that occurred. By examining the coloration of corn kernels, she traced genes through generations of corn plants. In 1931, she published the first genetic map for maize.

In 1936, she accepted a position at the University of Missouri at Columbia as an assistant professor. However, the position was short-lived. She was excluded from faculty meetings and many opportunities. Therefore, she left to find a a more welcoming work environment where she could have the freedom to do the experiments she wanted to.

She found a temporary home at Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Station for Experimental Evolution in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Here, she could focus on experiments. However, the director was so impressed by McClintock that it didn’t take long for a permanent position to be created for her. McClintock even played an important role in creating the Department of Genetics at Cold Spring Harbor, which is now one of the leading hubs for genetic research.

In 1951, she published the now-famous research about jumping genes. The idea of jumping genes, or transposons, is that the set of genetic materials (genome), which is contained on chromosomes, is not stationary. Instead, genetic elements (a DNA sequence) can sometimes change positions on a chromosome. This can affect nearby genes, turning some physical traits “on” or “off.” Many people criticized McClintock’s findings. Because of this, she stopped presenting her findings altogether. She only shared her findings with a trusted circle of colleagues.

“Over the many years, I truly enjoyed not being required to defend my interpretations. I could just work with the greatest of pleasure. I never felt the need nor the desire to defend my views. If I turned out to be wrong, I just forgot that I ever held such a view. It didn’t matter.” – Barbara McClintock, 1983

McClintock’s jumping genes research was indeed sound. Nearly 30 years after her discoveries, she was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for her discovery of mobile genetic elements.” McClintock worked on much more than just the jumping genes research she is most famous for. She was also the first to describe the idea that changes in our DNA can occur from gene expression rather than permanent changes in DNA sequencing–the concept we now know as epigenetics. McClintock was known to mentor graduate students, postdocs, and new investigators–especially women in the sciences. She also liked jazz music, even playing banjo in a jazz band at one point.

Not only is McClintock the first (and only!) woman to have received an unshared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, but she was also the first woman to be awarded the National Medal of Science. She was the third woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences (1944), and she was the first woman to become president of the Genetics Society of America (1945). She was also the first recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Grant.

McClintock’s work built a foundation for the understanding of genetics as we know it today.