The Lifeology team, or Lifeologists, as we like to call them, are spread across the country, bound by a belief that art can help science be easy, fun and accessible. Today, it’s time to meet our in-house content illustrator Laurel Shelley-Reuss.

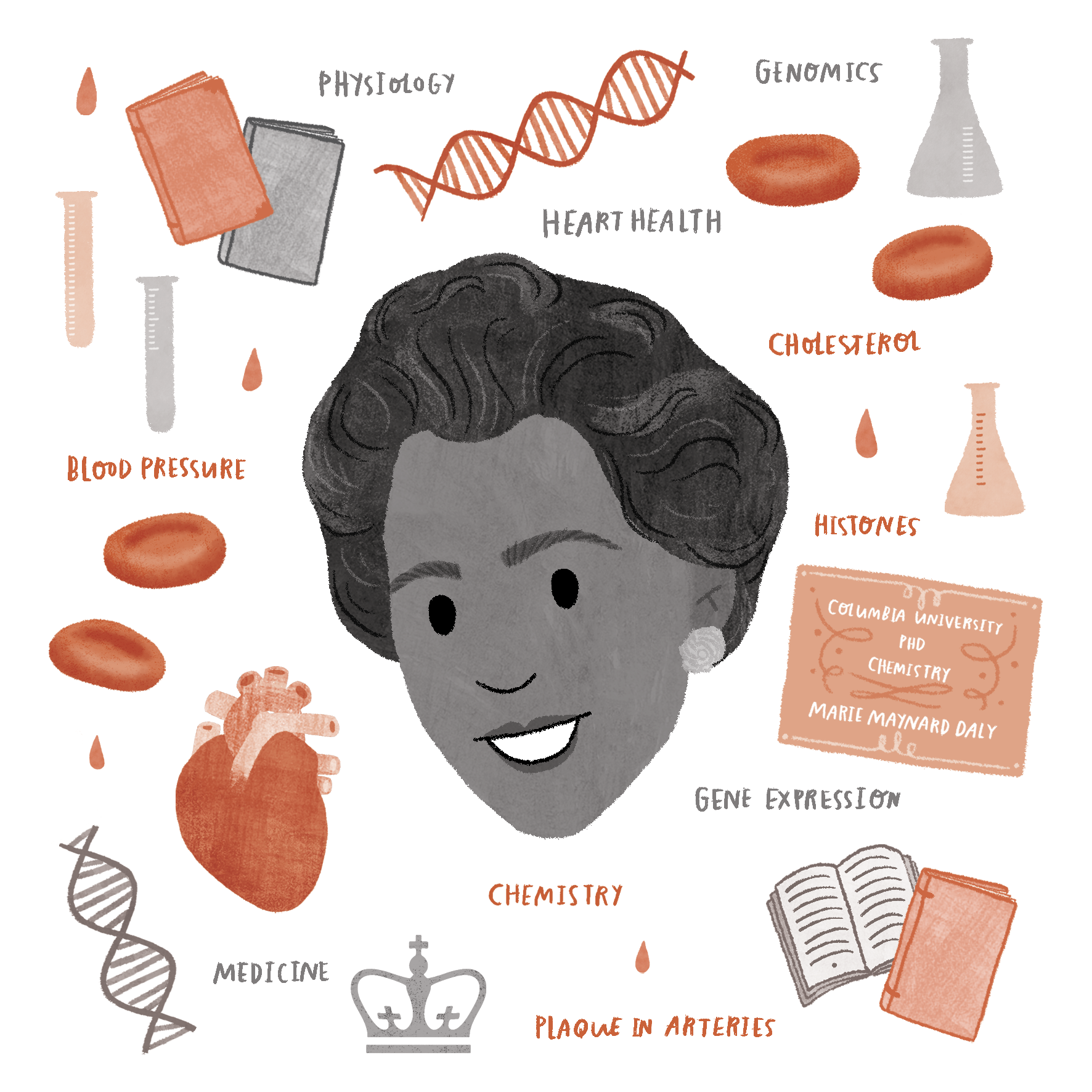

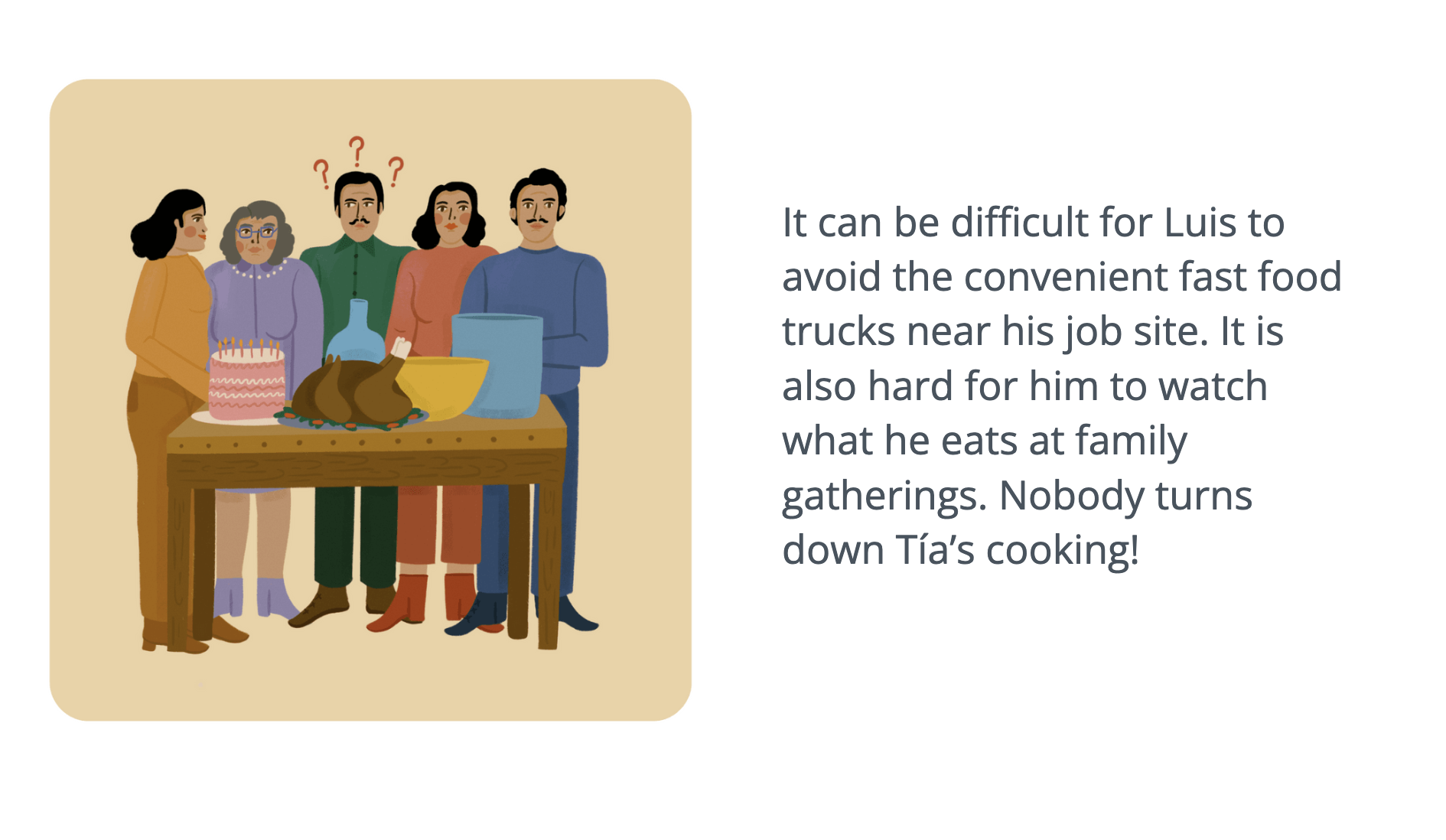

Laurel manages and creates illustration content for Lifeology courses that are part of the LIFE Ascent wellness program, which is a program based on learning, measuring and establishing healthy habits across multiple areas of health.

Laurel is based in Atlanta, GA and is an alumnus of Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). Let’s find out more about this lovely Lifeologist!

Tell us a little about yourself! How did you get into art?

When I was little, my parents had a friend who was a comic book artist. I spent a lot of time drawing with him in his studio and learning techniques while he worked, and he has been an amazing mentor and inspiration to me all my life. I studied art in college and worked on my own as a freelancer doing comics and freelance illustration (in addition to my graphic design day jobs!) until I finally found a home for myself at LifeOmic doing illustration full time.

What are your favorite things to illustrate?

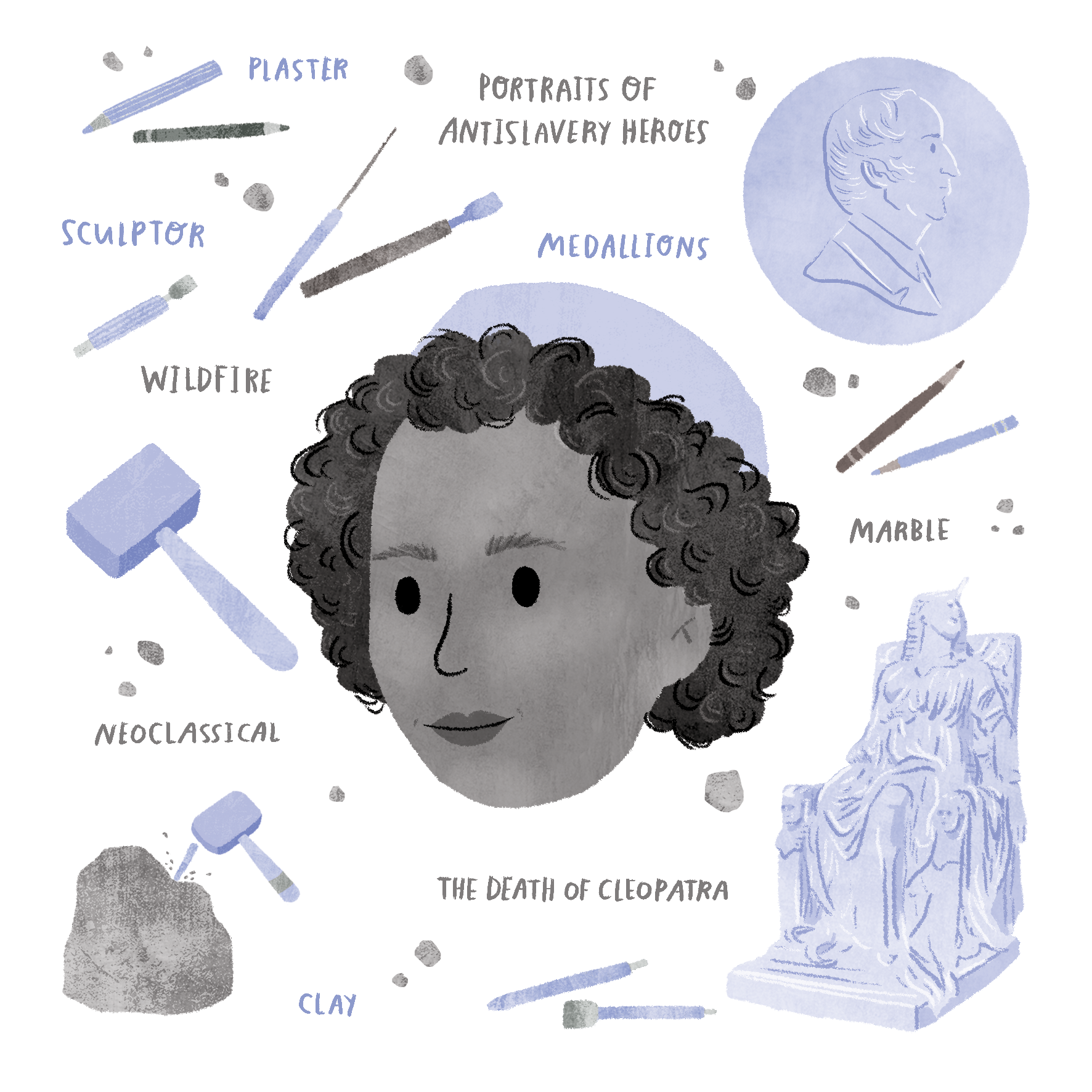

I love illustrating anything that invites the viewer to imagine themselves stepping into another world and learning and exploring something new. I am especially drawn to creating illustrations that are a little weird or a little magical in some way.

Security – Agency Matrix

Illustration courtesy of Laurel Shelley-Reuss

What art formats do you work with?

I work primarily as a digital illustrator in Photoshop. I especially like creating my own patterns and textures to include in my illustrations to give them a little more depth.

Can you describe what your creative process usually looks like?

My process usually starts with taking pictures around my city or doing research online. If I have a specific idea in mind I generally search for real-world examples to reference but sometimes even a pattern in a fence or a particularly cool lamp will prompt me to photograph and save it for a new illustration. I then draft up sketches on my tablet and choose my favorite composition to complete. I always try to keep in mind that art is a learning process and where my own weaknesses are. If I feel as though my architecture or my food depictions are lacking compared to other elements, I will go out of my way to study and practice those pieces until I improve.

Commuting – PHMP

Illustration courtesy of Laurel Shelley-Reuss

What has been your favorite science art project to create so far? Can you tell us a bit more about it?

For the last few months, I’ve been working on illustrated courses for the Life Ascent program centered around the cardiovascular system. It’s been incredible to be able to learn from the course while I am figuring out ways to help make concepts easy to understand for others.

![15-a-healthy-heart-also-impacts-your-mood[1] A man stands at the sink washing dishes. He is whistling and appears peaceful and relaxed.](https://lifeology.io/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/15-a-healthy-heart-also-impacts-your-mood1.png)

Illustrations for Cardiovascular Health LIFE Ascent courses

How can scientists or others work with you? And what does successful collaboration look like for you?

I think that a good collaboration works when both parties are willing to learn from one another. I am always happy to learn new topics from scientists or other experts and I get excited when I get to trade my knowledge about how to use illustration and storytelling to reach audiences. Art is an important component in the process of understanding and learning, but it needs a good foundation to really make an impact.

When you are getting started with a new science art project, what is the first thing you do?

The first question for me is ‘who is the project for?’ The style of illustration I use, the metaphors that I come up with–that all changes depending on who the intended audience is. I like to be able to read through a project and really get into the details before I start coming up with firm concepts–when I fully understand the message, it’s easier for me to make art that really conveys and helps an outside audience to understand as well. This is similar to my work in comics as well–if a writer comes to me with a half-finished script, it’s difficult to start without knowing the full picture. What if a character changes later and I need to foreshadow that? Details can make or break a project.

Can you talk a bit about visual storytelling, why it is important to you, and how you approach it?

Storytelling to me is one of the most important parts of being a visual artist, and my background in comics probably makes that obvious! Stories are how we remember, they’re how we experience the world, and when you get to see or interact with a new story, it can be more impactful than just reading a block of text.

Thunderstorm – Personal Work

Illustration courtesy of Laurel Shelley-Reuss

What tips do you have for scientists wanting to work with artists or get into science art?

I think the most important tip is to have a firm plan in mind when you reach out to an artist. Many freelance artists get approached regularly, and they’re more likely to respond positively to a project if they know all the details from the start! When I freelance, I regularly turn down jobs if they can’t give me important information up front.

What tips do you have for other science artists? For their careers or how to create visuals that broader audiences can relate to, enjoy, learn from, etc.?

I think the most important thing to remember for artists is that you need to tailor your work to the jobs you want. If your portfolio is full of illustrations that aren’t relevant or are the wrong style for science art projects, then you are unlikely to find work easily. Adjusting your portfolio when applying to a client is essential. Audiences and clients alike respond to you best when you are creating what you love, because you practice the things you love and they’re always your best work.

Telehealth – Vensure Employer Services

Illustration courtesy of Laurel Shelley-Reuss

What do you think are some important aspects of art/illustrations that help people better understand or enjoy science?

I think that having a visual representation or even a metaphor helps people see science concepts in a new light, and it helps them to remember them better. It sounds silly, but everyone remembers the math problems that are written out as stories–a train leaving the station going east at 5:00pm–as opposed to an actual equation. Storytelling sticks in our brain long after the base concept has been covered, and art and illustration tell that story.

Why should more scientists work with artists?

I think that artists and scientists can learn a lot from one another! I love getting exposed to new and exciting concepts and I think that scientists can really benefit from seeing their work interpreted and exposed to more general audiences. It takes a while to read a research paper, but a single illustration can grab attention long enough to get someone interested enough to keep going through it! In comics, we talk about having places for a reader to ‘rest,’ so that they remain engaged with the story, and breaking up text with art and illustration is a great way to give those readers a break so that they don’t give up entirely.

Laurel Shelley-Reuss