On May 11th, we hosted an Instagram Live chat with Luisa Torres, PhD and Jessica Malaty Rivera, MS about science communication and trust in science. This conversation stemmed from an earlier panel discussion at the 2021 SXSW conference. At the conference, Jessica joined a panel comprised of Kristen Bell, Ed Simcox, and Dr. Natalia Peart to discuss the health trust gap and ways to fix it. You can find more information about that conversation and see the full video here.

For our live Instagram chat, we asked Jessica to elaborate on the discussion about the health trust gap and answer questions from Luisa about addressing trust in science with science communication during this ~30-minute chat. Below, see a shortened and edited version of the chat. You can view the full chat on our Instagram.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: To start, I wanted to talk about trust in science and how misinformation can break down that trust. What do you think are some of the most pressing problems that we have to solve in that regard?

A: I think one of the biggest problems that we’re dealing with is that a lot of times research groups, universities, or even the US government consider science communication an afterthought. It’s something that’s not really formed into the plan from the very beginning. And it absolutely needs to be because science is only useful if it can be shared and understood broadly.

If we’re just thinking of [science communication] as an afterthought, we end up having to clean up more messes and misinformation.

One perfect example of that is how we didn’t really prioritize science communication on vaccines in the entire journey of Operation Warp Speed. I think a lot of the conspiracy theories were, in my opinion, inevitable because that’s what happens when you deal with emerging infectious diseases. I also think that people are not considering the fact that there are huge access issues. We’re talking about everything from internet speed to different abilities, whether things are available with alt text, and whether things are available in print. There’s a lot of assumptions that if it’s on a website people will see it, and that’s not the case. It needs to be in multiple formats and languages. A lot of times communication in science lacks the emotional and the cultural competence that’s needed to build trust. And when those two things aren’t considered you can further [the health trust] gap.

Q: What should science communicators consider about their audience in order to build trust?

A: I feel very strongly that science communication is not dumbing things down. I think we’d have to give people the benefit of the doubt and recognize that people probably are not sitting in data like you and I are all day every day.

The goal should always be to elevate people’s science and data literacy. And one way we can do that is to speak with compassion, empathy, and nuance so that people don’t feel shame or judged by not knowing things.

I don’t expect everybody to remember basic bio from high school or college. I also don’t expect them to understand the complexities of public health in the context of public health emergencies. Without the empathy, compassion, and patience that it requires, you lose people and cause more harm. There is not a one size fits all message in anything. You have to remember people’s history and current and historical traumas… There’s a lot of anti-vaccine messaging that can be perceived as laughable. But you have to know that if you mock, scoff at, or ridicule the people who are spreading it, you may not be creating opportunities to have them listen anymore. You could be pushing them further away, making them feel that scientists are elitists and that they don’t know how to speak the same language.

Q: There are people who distrust science because they have suffered from scientific malpractice. We have the example of the Tuskegee experiments, the birth control experiments with Puerto Rican women, and penicillin trials in Guatemala. As you mentioned, these groups are not monolithic and there is no one-size-fits-all strategy that can be applied to regain their trust. What’s the role of science communicators in this?

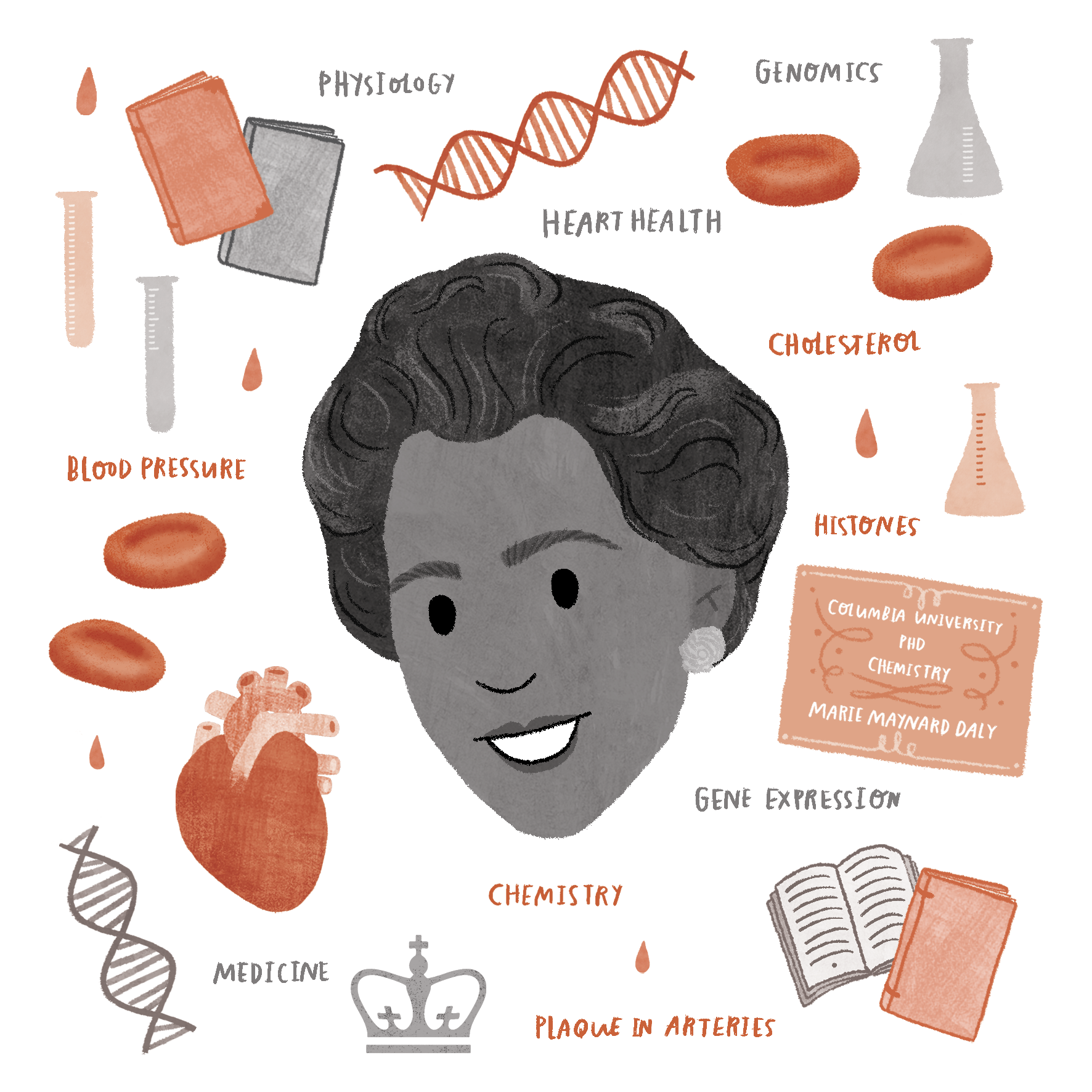

A: There needs to be diversity amongst science communicators. We need to be amplifying the voices of Black and Brown leaders in science who are gifted in not only the technical parts of research and development but also gifted at communicating it. People want to see people that look like them when it comes to topics that trigger a lot of fear and distrust. It’s less [about how to] fix the problem of people not being trusting [and more about how to] make the people communicating more trustworthy. We do that by having good representation, amplifying those voices, making sure that they’re in positions of leadership, and making sure that there’s representation in [clinical] trials. That’s how you make sure people are not feeling further detached from this.

Q: In this pandemic, there’s been an explosion of information online and in social media about COVID-19. How can you know who to trust? How do you personally tell whether a piece of information is trustworthy and worthy of being shared with your followers?

A: Everybody needs to do their due diligence. You need to check your sources constantly. There are people that have all kinds of degrees and credentials and associations and affiliations. Many of them are legitimate and can be corroborated by other people. Many of them are exaggerated or not legitimate, or just look fancier than they are. So I think that it requires pausing. Wait before you share. Ask yourself the basic questions of who, what, when, where, and why. And so it’s just patience to not draw any conclusions on first impressions… The goal is not to be first, the goal is to be accurate because you create more noise and more misinformation if you are sharing as soon as things come out.

Q: In the SXSW panel you touch on the problem of misleading, sensationalistic headlines that are click-baity but not necessarily accurate, which I think fuels mistrust. What should be the role of the media in this? How can we hold them to a higher standard?

A: In the time of COVID I’ve built relationships with a number of journalists, at various publications and newsrooms. And we’ve had those very awkward conversations. If you’re limited on your characters, whether it’s for a tweet or for a headline, how can you resist the temptation for clicks and eyes? We knew it was going to happen with vaccines because it always happens with vaccines. A vaccination happens and then an event, which is unrelated to the vaccine, is thrown into the same sentence. And therefore it causes people to correlate those things and assume causation for those two things. I think it requires folks like us, either unpacking, debunking, translating those headlines, and also just pushing back on those newsrooms. Everybody can be a science communicator in this context by helping increase understanding and not pressing for more fear or confusion.

What do you think the role of science communicators should be in preventing the spread of misinformation and helping people to trust science?

I think a lot of people think that science communication is just debunking and myth-busting. And it’s really not. It’s with the goal of increasing people’s science and data literacy. If you look back at a lot of the conspiracies that have been circulating in the pandemic, a lot of them are just copy-paste from previous experiences. They’ve just been modified to sound related to COVID-19, but a lot of them lack originality. [Science communication is about] anticipating those problems and preparing people for them so that you’re not doing as much mess cleaning and damage control.

I also think that as science communicators, we need to collaborate a lot. We have to be working together because this is not one person’s job. We each add our own experiences, our own nuance, our own lexicon that helps make messages stronger and more memorable. And I think that to do it with other people is the best way to do it.

What kind of information do you think is lacking out there that science communicators can work together on?

Visuals! I think that between data visualization and science art, there’s not enough of it. And I think those are some of the most impactful pieces of science communication. I have loved working with Lifeology on those two courses. We did one on vaccines and one on new mutations, and it was so amazing to see words and technical terms in virology turn into characters and little faces. I think if more people focused on ways to visualize and illustrate science for many people’s minds, that’s really how comprehension really clicks for a bunch of people.

How do you run your Instagram ask-me-anything? What’s your goal? How do you assess whether you are accomplishing those goals?

The reason why I started posting on social media was because I got so many of the same questions from people who knew my background in emerging infectious diseases. And I thought I might as well just put it in someplace that it’s easily accessible, so I’m not sending the same text message over and over. And it’s turned into a whole thing. The weekend AMA is probably the most fruitful thing that’s come out of my Instagram because it is so interactive. And I see trends in people’s misunderstanding, confusion or fears as it relates to things like headlines or data, and I address it in a simple and short way. I try my best to answer questions with grace, patience and empathy because that’s where I’ve seen these wins. I’ve seen more people than I can count replying that they now feel comfortable getting the vaccine because of the information that I shared, which shows me that it’s working. It shows me that even if that one person got vaccinated, that’s one less lost life. And the people around them are safer because that person is vaccinated. So it’s very motivating to keep going, even though it’s a lot of work.