Write Science Poetry with us this month for the Lifeology SciComm Challenge!

Whether you see how the beauty and intricacy of poetry can aid science communication, or you’re new to the wonderful world of poetry and you want to learn the language of symbolism, try your hand at some science-themed poem for our monthly challenge.

You might realise that translating your message into another form can be a valuable exercise in the communication of science!

To help inspire some creativity for this challenge, we (Jordan & Alex) have collected a handful of science poems that really piqued our interest. Take a moment to take in these poems from historical and contemporary scientific figures.

If these connect with you, share your inspiration in the form of your own science poem!

Alex’s Favorite Poems

by Alex Gilmore, Lifeology Summer Intern

I have chosen three different poems that I hope you will enjoy, and that might serve as inspiration for you to attempt the July challenge of the month to write a science poem for yourself.

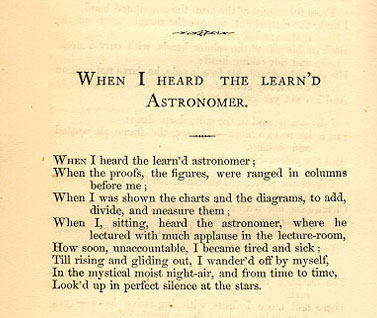

1. ‘When I Heard The Learn’d Astronomer’

The first poem I have chosen is ‘When I Heard The Learn’d Astronomer’ by American poet Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892). It was published in his 1865 poetry collection ‘Drum-Taps’.

The poem is written from the perspective of a student who is disinterested in the analytical study of astronomy, and prefers to look up and the stars in silence, on their own terms.

This might seem a surprising poem for a science-lover to choose, since it does not paint science in a particularly favourable light. But oddly, the way the student in the poem feels about science is a bit like how I have often felt about poetry.

My first experiences of poetry were in the classroom. In preparation for intimidating exams, I would analyse and interpret what the poems we were assigned really meant. I saw it as trying to decipher what the poet was trying to do; trying to find the correct interpretation. There was a right and a wrong, I thought, just like trying to solve for X.

But sometimes, if I am honest, I didn’t get much from reading a poem. No covert hidden deeper meaning jumped out at me. This would lead me to think I’m not clever enough to “get it” and feel disconnected and even intimidated by poetry.

Since then, however, I have stumbled upon poems in my own time. I realised I enjoy a poem in a different way if I’m not trying to understand and analyse it. I’m just feeling it, and letting the words sink in, and thinking about how I feel when I read it.

I “wander off by myself” like the student in the poem. Where does it make my mind wander? What does it remind me of from my own life? Maybe it’s okay if a poem means something different to me than to other people, or even to the author. It might even take on new meanings for me on different days depending on my mood and what has been on my mind.

As a science communication student, the poem makes me wonder if the problem for the student protagonist is really about the way the astronomer analyzes the stars, or if it is about how the astronomy is communicated? If it were communicated in a different way, might the science add to the magic of the stars?

Does knowing the proofs, mechanisms and calculations behind nature make you see more or less? It has often been argued that analyzing nature destroys its beauty. But some, like theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, have made the counter-argument that science in fact reveals hidden beauty that couldn’t be otherwise seen. To me, the two poems below demonstrate how this is possible.

You can listen to Feynman share his views on the topic in a beautifully animated video shown at The World Science Festival.

2. ‘Singularity’

The second poem I have selected is written by a modern, living poet Marie Howe who was named the state poet for New York in 2012. It’s called ‘Singularity’, and it was inspired by Stephen Hawking following his death.

This poem touches on science; from the geology of rock formation, to the biology of human evolution and even to the physics of the big bang. But It is nothing like a science lesson. It isn’t laborious to read, and the language is simple, thought-provoking, and human.

In April this year, a video of an animated reading of this poem was made for “The Universe in Verse”, an annual festival celebrating science and nature through poetry (which had to be online due to the pandemic). This was produced by SALT and Maria Popova, with music by Zoe Keating and illustrations by Elena Skoreyko Wagner, in what they describe as a “multi-woman labour of love”.

Having already read the poem myself, I found that listening to it being read by someone else – and brought to life by the beautiful visuals – meant the poem took on new levels of meaning. She read it slower than I had read it in my head. Where the reader paused was different to where I paused. Different words were emphasised, and I noticed details I had missed before.

Reading aloud can provide a fresh perspective. Science poets Dom Conlon and Rachel Rayner both included reading your poems aloud as one of their top tips for writing your own poem in our science poetry Q&A.

3. ‘The Stuff of Stars’

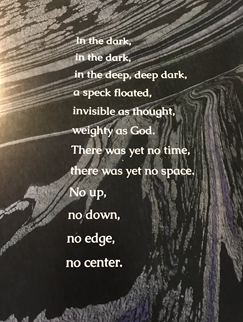

My final choice is “The Stuff of Stars”. This is a picture book aimed at children, written by Marion Dane Bauer and illustrated by Ekua Holmes.

The first page of ‘The Stuff of Stars’, found alongside more of the text on Brain Pickings.

In some ways it is similar to the above poem, ‘Singularity’. It deals with big-picture themes of the origin of life and our significance within the universe. It prompts reflection on how improbable and precious life is.

One reason I chose this poem is because it is accompanied by striking visuals. As with ‘Singularity’, it is presented alongside enticing artwork. The marbled backgrounds are abstract, dreamy and ethereal. They could be indicative of huge galaxies or stained microscopic cells, and they add to the deep sense of wonder of the words.

If you do feel inspired to try our challenge of the month and write your own science poem, be sure to check out our science poet Q&A for expert tips. You might consider reaching out to an artist, asking them to respond to the poem in a visual way.

Jordan’s Favorite Poems

by Jordan Pennells, Lifeology Community Manager

I have narrowed down my shortlist of science poems – collected from my shallow dive into the ocean of poetry – into these 3 fantastic pieces. They are nicely distinct in subject, style & situation in history. I hope you enjoy reading them (it may take several reading iterations before fully appreciating them – one of the suggestions that our science poetry experts shared during our Slack Q&A chat last week) and please share any inspiration you have with the Lifeology community.

Stars in the center of the globular cluster Messier M22. Credit: NASA via Wikimedia Commons.

1. A Universe of Atoms, An Atom In The Universe

This first poem is by the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman – as much of a cult hero that the scientific community has ever had. I really appreciate the parallel in this poem between the water molecules in the ocean forming a wave & the atoms in our brains that emerge into consciousness. It’s of a simple style, but it portrays a profound message of separation, yet oneness! And plays around with the idea of universe. Enjoy.

By Richard Feynman

I stand at the seashore, alone, and start to think.

There are the rushing waves

mountains of molecules

each stupidly minding its own business

trillions apart

yet forming white surf in unison.

Ages on ages,

before any eyes could see

year after year,

thunderously pounding the shore as now.

For whom? For what?

On a dead planet

with no life to entertain.

Never at rest

tortured by energy

wasted prodigiously by the sun

poured into space.

A mite makes the sea roar.

Deep in the sea

all molecules repeat

the patterns of one another

till complex new ones are formed.

They make others like themselves

and a new dance starts.

Growing in size and complexity

living things

masses of atoms

DNA, protein

dancing a pattern ever more intricate.

Out of the cradle

onto dry land

here it is

standing:

atoms with consciousness;

matter with curiosity.

Stands at the sea,

wonders at wondering: I

a universe of atoms

an atom in the universe.

2. A Problem in Dynamics

James Clerk Maxwell is a 19th Century mathematical physicist and a self-proclaimed poet. This poem of his fascinated me due to his ability to recapitulate a scientific challenge in poetic form. There’s obviously a wall of jargon throughout that limits understanding of the underlying concepts for anyone that hasn’t deeply studied Statics & Dynamics – but I could definitely still appreciate the way in which science is communicated in this poem without exactly understanding the science of each line. This highlights to me that you can enjoy the flow of a poem even if you don’t connect with the content.

By James Clerk Maxwell

An inextensible heavy chain

Lies on a smooth horizontal plane,

An impulsive force is applied at A,

Required the initial motion of K.

Let ds be the infinitesimal link,

Of which for the present we’ve only to think;

Let T be the tension, and T + dT

The same for the end that is nearest to B.

Let a be put, by a common convention,

For the angle at M ‘twixt OX and the tension;

Let Vt and Vn be ds‘s velocities,

Of which Vt along and Vn across it is;

Then Vn/Vt the tangent will equal,

Of the angle of starting worked out in the sequel.

In working the problem the first thing of course is

To equate the impressed and effectual forces.

K is tugged by two tensions, whose difference dT

Must equal the element’s mass into Vt.

Vn must be due to the force perpendicular

To ds‘s direction, which shows the particular

Advantage of using da to serve at your

Pleasure to estimate ds‘s curvature.

For Vn into mass of a unit of chain

Must equal the curvature into the strain.

Thus managing cause and effect to discriminate,

The student must fruitlessly try to eliminate,

And painfully learn, that in order to do it, he

Must find the Equation of Continuity.

The reason is this, that the tough little element,

Which the force of impulsion to beat to a jelly meant,

Was endowed with a property incomprehensible,

And was “given,” in the language of Shop, “inexten-sible.”

It therefore with such pertinacity odd defied

The force which the length of the chain should have modified,

That its stubborn example may possibly yet recall

These overgrown rhymes to their prosody metrical.

The condition is got by resolving again,

According to axes assumed in the plane.

If then you reduce to the tangent and normal,

You will find the equation more neat tho’ less formal.

The condition thus found after these preparations,

When duly combined with the former equations,

Will give you another, in which differentials

(When the chain forms a circle), become in essentials

No harder than those that we easily solve

In the time a T totum would take to revolve.

Now joyfully leaving ds to itself, a-

Ttend to the values of T and of a.

The chain undergoes a distorting convulsion,

Produced first at A by the force of impulsion.

In magnitude R, in direction tangential,

Equating this R to the form exponential,

Obtained for the tension when a is zero,

It will measure the tug, such a tug as the “hero

Plume-waving” experienced, tied to the chariot.

But when dragged by the heels his grim head could not carry aught,

So give a its due at the end of the chain,

And the tension ought there to be zero again.

From these two conditions we get three equations,

Which serve to determine the proper relations

Between the first impulse and each coefficient

In the form for the tension, and this is sufficient

To work out the problem, and then, if you choose,

You may turn it and twist it the Dons to amuse.

3. Limerick for NASA’s OSIRIS-REx

The last poem I’ve chosen is much lighter in its Limerick form than the previous one, but still with a deep concept underpinning it – the exploration of our universe. I LOVE the imagery of interstellar objects as a “treasure trove” waiting to be discovered.

This poem was written for NASA’s first asteroid sampling spacecraft – OSIRIS-REx – starting on a 7-year mission to collect samples from the asteroid Bennu.

By NASA’s OSIRIS-REx (@OSIRISREx)