This month, Lifeology is running a science poetry challenge! You can learn more about it here.

To get you started, we’ve interviewed below several amazing science poets. They’ve offered advice and also their thoughts and experiences on poetry and how it can improve our communication of science.

Learn more below from science poetry researcher and writer Rachel Rayner, astronomy-inspired poet and children’s book author Dom Conlon, and cancer researcher Elicia Fyle, the “Rhyming Scientist” who currently works as a Scientific Officer researching a childhood cancer known as neuroblastoma, while also writing science poetry in her spare time.

Don’t see your burning question about science poetry writing answered below? Join a Slack live-chat with these poets this Friday, July 10! Details here.

Q&A

- What 3 tips would you offer a scientist writing a poem?

- How did you get into science poetry?

- What do you love about science poetry?

- Do you have an example of a science poem or science poets you love?

- What does poetry have to offer science in particular, perhaps different than other scicomm formats?

- How does science & poetry offer complementary ways of sense-making in the world?

- Why is it important for scientists to express their emotion (through poetry)?

- How do you balance style and accuracy in science poetry?

- How can one get started?

- How do you share your science poetry?

What 3 tips would you offer a scientist writing a poem?

Rachel Rayner: 1) Write write write – get everything out. Allow yourself to write rubbish – it doesn’t matter! Pick up something in your stream of writing that you want to develop further, then write write write on that. Poetry is best when there is a discovery, so give yourself the space to discover something about your topic.

2) Thoroughly research the topic you want to write about it. The more angles you understand your topic from, the more interesting your poetic snapshot of it will be.

3) Read it aloud. Then read it aloud again, and again, and again. Then, get someone else to read it aloud to you. Discover what words or phrases that are being stumbled over and rewrite them. Poetry is an aural medium – it is (usually) written to be heard. Allow yourself to enjoy the sounds and cadences of the poem.

P.S. If you’re struggling, get a prompt from others. I’ll ask a friend to give me a topic, or take a line I enjoyed from a movie and expand on that idea. Recently, a comment about sliding around the earth led me to write a poem on the moment of inertia (I did the calculations and everything).

Similarly to the above, explore all the strange and wonderful vocabulary we have in our languages. If there is a word you really love, that may be a bit unusual, then use it! Build the poem around it.

If you are still stuck, write a paragraph on your topic – don’t aim for a poem. Write it as a letter to someone. When I do this, I take this block of text and put line breaks in here and there until it “looks like” a poem. It will inevitably be a terrible poem (broken prose does not a poem make), but it gives me a place to start. I will then edit it like mad to bring in more imagery, rhythm and maybe even some rhyme. I find it helps get what I want to say on the paper, without worrying about form yet.

Dom Conlon: 1) Write as simply as you can.

2) Write lots and find the phrases which seem to feel true to you and then develop them into the poem.

3) Read everything out loud. It’s easy to let our inner voice take shortcuts. I create images after a long internal dialogue where I’ve chased a rabbit down so many holes that I get lost but because it’s been my journey I don’t always acknowledge how lost I am and so emerge somewhere the reader doesn’t recognize. In fact, this metaphor might be one of those places. So I’ll refer you back to item 1: write simply.

Elicia Fyle: 1) Use poetry styles such as repetition and rhyming.

2) Do your research on the topic that you’ll be discussing.

3) Don’t make your poem too long or too short.

How did you get into science poetry?

Rachel Rayner: I am passionate about both the arts and sciences. I see them as two parts of a whole: you can’t have one without the other. My undergraduate degree was filled with subjects in both the arts (Art History & Theory, English Literature, Life Drawing) and the sciences (Physics, Mathematics), and I couldn’t imagine having it any other way. I’ve used the knowledge and skills from these areas in all of my science communication roles – from designing science exhibits to now writing science poetry.

I have always enjoyed reading and writing poetry since I was a small child for reasons I will never truly know. But I hadn’t heard of science poetry specifically until I attended the 2016 Quantum Words festival Sydney, Australia. They had science poets Carol Jenkins and Alicia Sometimes as panelists. It just made sense to me: science has such a rich and beautiful vocabulary which should be captured in poetic form. So it was a natural progression to start mining my scientific background for inspiration and content.

Dom Conlon: The Moon made me do it. I’ve been interested in astronomy ever since I was a child but I chose to study literature. The interest in science stayed with me and when I began writing for children, I knew I wanted to write from a position of being fascinated in how the world works.

Elicia Fyle: I got into science poetry through a talk that I gave at a cancer research conference in 2019. I thought that a good way to grab the audience’s attention would be to do a rhyming poetry performance, explaining the work that I do. It went really well, and was a nice change to conference talks!

What do you love about science poetry?

Rachel Rayner: Who doesn’t love it when their two favourite things work together? Like cheese and toast.

I love that scientific language and knowledge gets another avenue to shine in. When science combines with poetry, the resulting product can be delightful, charming, intriguing, novel, mystifying and eye-opening.

I love that it isn’t something that is only read, either. Writing science poetry is used in classrooms to encourage a deeper engagement with the subject matter.

I love watching this field grow. Well, actually, it’s always been there (John Keats was trained as a medical doctor), but now that it has a name, science poetry can much easily be collected and shared. There’s a real momentum behind it, which I think speaks well for it as an engaging communication tool. There are a number of poets and projects that create and support science poetry, such as the Sciku project or the newly released journal, Consilience. I’m also learning more and more about the field every day.

Dom Conlon: It inspires curiosity in understanding the scientific principles whilst also holding up the poetic beauty of life. I hear the best mathematicians talk about how beautiful maths is and I believe them. As I am very much a non-mathematician I want some way to gain insight into that beauty. Poetry helps.

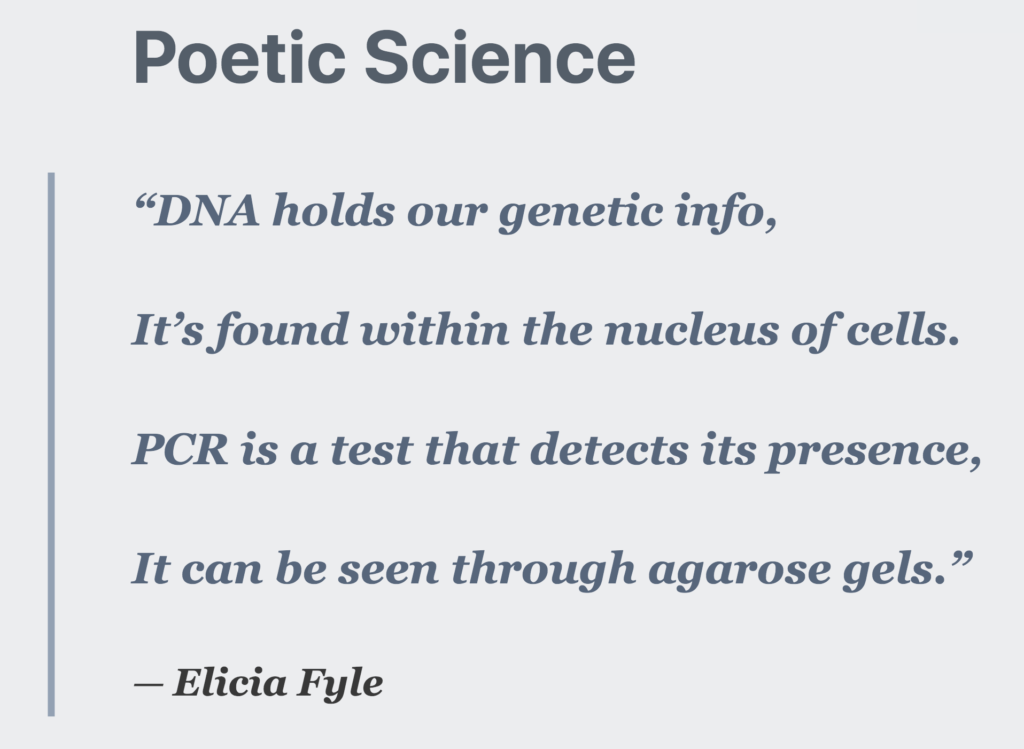

Elicia Fyle: I love the fact that science poetry allows the arts and the sciences to merge together. It’s great that scientific concepts can be explained in a poetic style that’s pleasing to the ears.

Do you have an example of a science poem or science poets you love?

Rachel Rayner: Poetry is very subjective, but the more widely you read, or go to poetry events, the more likely it will be for you to find your favourite poet. Carol Jenkins is my favourite, I keep coming back to her poems as they connect with me more than others. The use of mathematics and unique perspective, but also relevance, that draws me in. But there are so many incredible science poets working now. I read a lot of work by Tricia Dearborn (who is the guest editor of the upcoming Rabbit publication, which will just feature science poetry), Katharine Coles or πO, a Greek-Australian poet who has matrices as poems. It’s wild.

In an interview from nearly twenty years ago, πO (or Pi O) described a poem as “A miniature program that helps cut-out the furrows in the brain. A social matrix that can put the pieces together and make sense of it.” And gives this advice on how to tell if a piece of writing is a poem: “It gives you a hit! It does something to you that you know is different from anything else.”

There’s a lot of poetry happening out there. You just have to start looking. On instagram, @AntarcticPoetry shares the results of their annual competition for photographed poetry, and

Poetry on the Move has a podcast episode discussing science poetry with a couple of the names I’ve mentioned. It’s worth a listen!

Dom Conlon: I’m going to go with a poet I was made aware of by Sam Illingworth – the master of science poetry. In his book ‘A Sonnet To Science’ he features the astronomer Rebecca Elson. This poem is widely-quoted and is particularly relevant in the context of what we’ve been talking about. It’s called ‘Theories of Everything’.

What does poetry have to offer science in particular, perhaps different than other scicomm formats?

Rachel Rayner: Poetry is an old and ancient art that still exists today because people do enjoy it – they love reading and writing it. Poetry is something deeply personal, and so can create really strong connections and memorable moments.

Dom Conlon: Poetry is one of those forms which many people have written off as being elite or difficult. You have to glean its meaning or ponder the deeper truth. And yet once people start to write their own poetry they quickly see how a poem is the most natural form of expression in the world. One person might find they work best with spoken word, another in rap, another in prose-poems. It’s an individual choice but at the heart of this decision, or path, is the fact the poetry is a way you or I can share the truth as we see it.

Poetry is all about seeing the world in a deeper way. It offers insight so that the rest of us can jump in and participate. I also believe everyone can communicate through poetry.

Elicia Fyle: I believe that science poetry is an excellent communication medium and should be explored more often. Poetry is something that can draw people’s attention. It can let people be informed of the latest science research in a clearer way. Suggestions of using science poetry include doing short, snappy, and informative poetry pieces on TV ads, radio, websites, etc.

Poetry allows scientists to truly think about the research that they are doing and to portray it in a way that is easy to understand. It gives a fun and creative take on science, enabling those interested in science to understand research in a simpler way.

How does science & poetry offer complementary ways of sense-making in the world?

Rachel Rayner: Science gives poetry a wealth of ideas to explore, vocabulary to use, unusual ways of looking at our universe. It has inductive reasoning, logic, and imagery (such as data visualizations). Poetry gives science a new format to layout those ideas, allows for emotion and aesthetics, distillation of thought, and further pushes the unusual way of looking at things. Apparently, poet-naturalist René-Richard Castel said: “A poet must not aim to teach and advance a science as much as to show its advantages and make it loved.”

Science and poetry are also similar in many ways. Both are about detailed observations.

Elicia Fyle: I believe that science and the arts work hand-in-hand in this world. For instance, one can understand the importance of photosynthesis, while also appreciating the colourful leaves of autumn. Therefore, science and poetry can offer complementary ways of making sense in this world by providing peaceful clarity of how the world works.

Why is it important for scientists to express their emotion (through poetry)?

Rachel Rayner: The current world seems to disagree with facts: we’ve anti-vaxxers, flat earthers, climate deniers and now COVID conspirators. In science communication, there has been a revaluation of how we can best communicate important messages. Facts aren’t working – humans make decisions based on emotion rather than rational thought (however we might try to convince ourselves otherwise). So creating something emotive around research can be a powerful way to connect. Also, scientists have emotions! There’s no need to lock it out just because you can’t put it into a lab report. This is a chance to share passions.

Also check out this incredible project, aimed at sharing how scientists feel about climate change.

Dom Conlon: Because if you want to bring anyone on a journey with you, then you need to create an emotional bond. There are few things more appealing than being swept up by a person’s enthusiasm for a subject. If we can understand why someone loves a topic or an aspect of research, then that really helps us to listen more closely.

Elicia Fyle: It is important for scientists to express their emotion through poetry because of the fast-paced lives that scientists often go through. Many scientists may find it challenging to balance their careers and their personal lives. The constant search for a publication and grants can be overwhelming. This is why poetry can be an important way for scientists to be in touch with their emotions as a way of artistic therapy.

Scientists have emotions, too. We should express them. Photo by Cristian Escobar on Unsplash.

How do you balance style and accuracy in science poetry?

Rachel Rayner: The idea of having “poetic license” doesn’t work in a science poem to the same extent. Accuracy doesn’t have to kill creativity – personify the virus, give the molecule thoughts! But don’t let that molecule live in a benzene ring if it is a pyridine.

It is a delicate balance, though. I use the editing process to explore all the different ways to say one thing, matching the style whilst still being accurate. It is just experimenting with words throughout the editing process.

Editing is so important in a poem. The more you edit, the more you find how many ways there are to write a simple line – with both accuracy and style. Poet Marie Howe gives the advice of “make it so that when you shake it won’t rattle, or that nothing will fall out” which I think is a lovely way to help conceptualize whether the poem on the page is really as tight as it should be. You don’t want it rattling with unnecessary words!

Dom Conlon: I don’t think there should be a clash between the two. If a style choice calls for contradicting or ignoring the science then I’d suggest a re-think. You can leave that for your science-fiction action film.

Elicia Fyle: I believe that planning is important. It’s good to know what each stanza would be about. The poem should flow, and build on scientific concepts as the poem progresses. As a rhyming poet, I often think of rhyming words first, and circulate sentences around these words. It’s not as hard as people may think!

How can one get started?

Rachel Rayner: An appetite for poetry. Read poetry. All and any poetry. You’ll find yourself gravitating towards styles you like. Perhaps it’s the ones that use math in some way, have a strict rhythm or rhyme scheme, maybe something quirky and highly imaginative, or thought-provoking. A poem that I really enjoyed writing was sparked by Billy Collin’s “Questions About Angels” – he has not written a science poem, but I was inspired to write in a similar way about photons. I’m not there yet, but I’m working on it!

Dom Conlon: Reading. Read poetry. Not just science poetry but all kinds of poetry. Find the poets who speak to you and think about why that might be. Perhaps it’s the language, perhaps it’s the form.

Elicia Fyle: Skills that I would recommend are knowing your target audience, gaining inspiration from other poets/poems, planning poems (from the length of the poem to the content), making use of repetition and rhyming as poetry styles, and being creative. Have fun!

How do you share your science poetry?

Rachel Rayner: Great question! And an important one. It took me a long time to be confident enough to start sharing my poetry, but I really don’t know what was holding me back: just go for it!

There are a multitude of poetry journals online, and some that are still being published. It is worth checking if your local area has a writers’ group. This can really help in finding out where people locally are sharing their poems, but also tips on publications further afield. Science journals may accept poetry too, as something different. It is worth asking, or even suggesting that they include some poetry! Here, the Medical Journal of Australia has been known to publish a poem or two.

Then, of course, there are always the social media platforms and podcasts. Poetry readings are known to occasionally be science themed, but live readings may not be on the cards for a while. There’s some Instagram live poetry events happening, to fill in the void for now.

As a science communicator, you’re in a great position to create a new space to share science poetry. Before I even started sharing my own poetry, I was talking at festivals and conferences about science poetry and the joy that it can bring.

Dom Conlon: I have two books out at the moment. Both are primarily for children but I’ve been told that many adults are responding to them as well. Personally I know that before trying to tackle a more difficult book on a subject, I will often look to children’s literature first.

So one of my books is called This Rock That Rock and it’s inspired by our moon. I look at it from scientific, historical, personal, and aspirational angles. The other book is a poem presented as a picture book about the different species of hares around the world. I also post videos on YouTube and share individual poems on Twitter/Instagram and my website.