In this post, Anna reflects upon the childhood experiences that shaped the writing & illustration of her book Ada Lovelace: The Fantastically Feminist (and Totally True) Story of the Mathematician Extraordinaire. She also reflects on the books she had when growing up, which primarily portrayed men in STEAM (Science-Technology-Engineering-Arts-Mathematics) roles.

In Dick King Smith’s Sophie book series, Sophie wants to be “a Lady Farmer”. I was tickled when I read this as a seven-year-old. I decided I wanted to be a Lady Farmer, too. I’d learnt to read on a strict diet of Famous Five books, where it was made very clear that boys were better than girls at almost anything. Tomboy George is eternally hoping strangers mistake her as a male, always lapping up the praise when she’s told she’s “as good as a boy”. Always on the boys’ side for anything; never insisting on equal rights for women. During Five on a Hike Together (by Enid Blyton), Julian tells George in response to her millionth outburst of “It’s stupid being a girl!”:

“You may look like a boy and behave like a boy, but you’re a girl all the same. And like it or not, girls have got to be taken care of”.

And so, primary-school-aged me decided that I too thought it was stupid to be a girl. And here, Sophie was presenting me with the chance to do a “man’s” job, as a “Lady”. A Lady Farmer! How exciting!

How awfully backward, in retrospect. Why must “Lady” be added? What’s wrong with being a regular, normal farmer who just happens to be female?

I started to think about portrayals of other careers in books I read growing up. I was struck that there were certainly a lot of policemen, firemen, postmen, businessmen. And often, these male characters had wives or female friends who either didn’t have jobs at all, or if they did, more often than not they were child-care or home-care related. Where were the policewomen, firewomen, postwomen? I went through all my childhood books, noting the mentioned jobs and careers.

And that’s when it hit me:

Books I had while growing up had primarily portrayed just men in STEAM roles.

Scientist Uncle Quentin in the Famous Five books, Dr Jekyll, Victor Frankenstein, arguably even George’s Marvellous Medicine, analyst Mr Brown of Paddington, bank clerk Mr Darling of Peter Pan, Dr Doolittle, Dr Foster…

Even TV shows and films we were exposed to as children had predominately male STEAM figures. Indiana Jones, Q, Brains from Thunderbirds, Ross Geller, Buzz Lightyear, Wallace of Wallace and Gromit, Doc in Back to the Future… the list goes on.

All of these male figures had exciting and intriguing jobs. All of them reinforced George’s idea that boys were better than girls.

As I got older, I left my farmer dreams behind and set my heart on illustration. I fell into the children’s book world, where I first began to realise that I could help other little girls growing up from thinking that boys were better than girls, and only boys could have cool, interesting jobs.

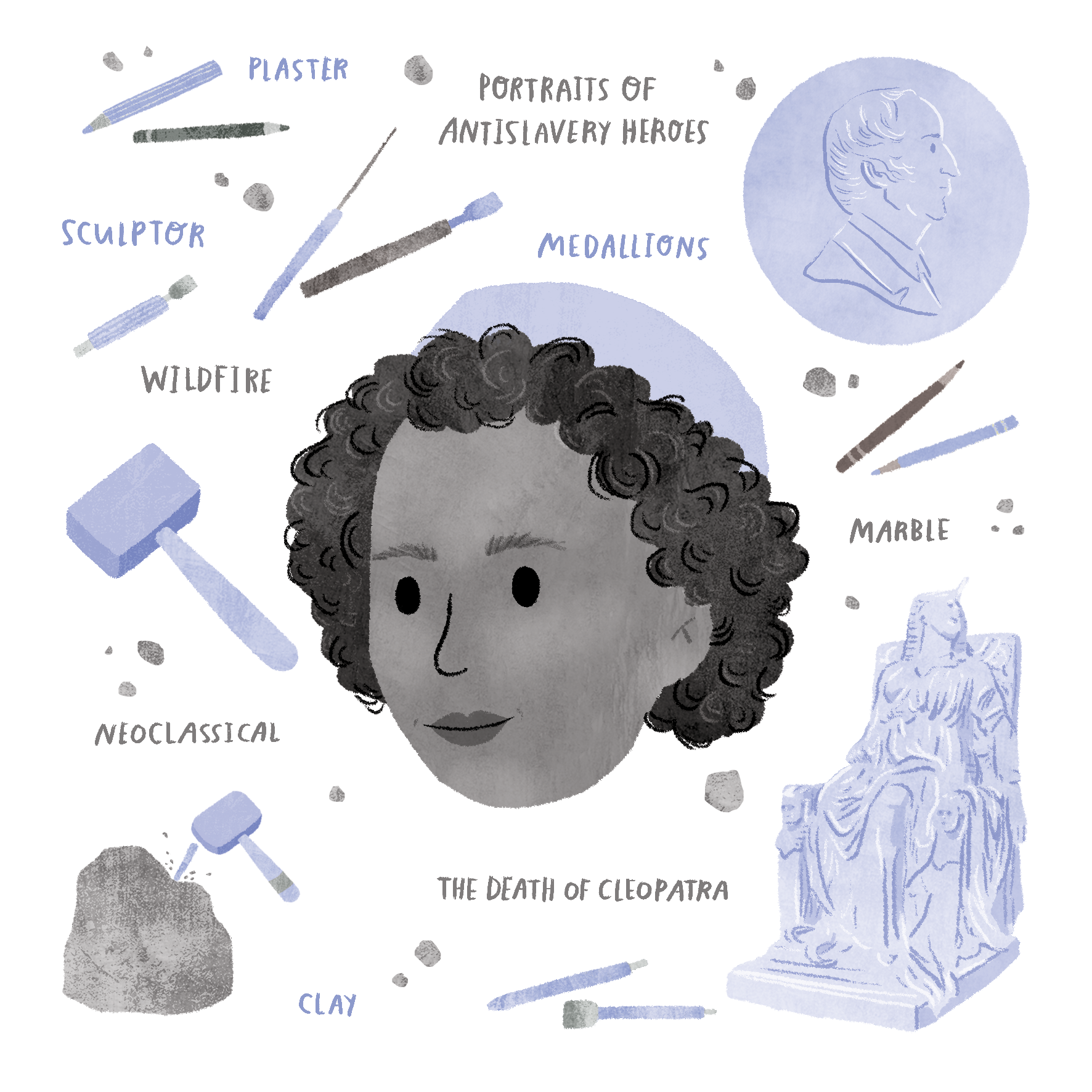

I had come across Ada Lovelace on one of those internet deep dives when you find yourself clicking further and further from your original Google search. I hadn’t heard of her before, but there she was, on a page of historical mathematicians, one of the few females among hoards of men. She stuck out! There was a painting of her in a purple dress with crazy fancy hair. She looked so appealing. And there were beautiful quotes about her from her friends, calling her a “lady fairy” and an “enchantress of numbers”.

The internet informed me that she was the first computer programmer and that she was from the 1800’s, but I couldn’t find much else. But I was already obsessed.

I got in touch with the BBC archives, and they pinged over old radio shows with mathematicians singing her praises and explaining her life story. I listened, read, Googled, absorbed anything I could find about her. I went to the science museum in London and saw the machine she helped design, The Analytical Engine, and also a lock of Ada’s actual hair, which made her feel so real. It seemed other people had suddenly discovered her too, because slowly TV shows and articles and books began to pop up about Ada, and I could learn more and more.

…there were beautiful quotes about her from her friends, calling her a “lady fairy” and an “enchantress of numbers”

In brief, Ada was the world’s first computer programmer – 100 years before the first computer was even invented. She grew up in a strict household, and sought out people to teach her maths and science for her whole life despite living in a time when women weren’t expected to be educated. Fascinated by engines, her free time was spent designing machines to count and fly and write music.

The more I read, the more I grew a deep sense of loyalty to Ada and an absolute need to tell her story. I loved her because her life was so interesting and unusual, and she had such a great character. She was passionate and determined, but also an imaginative rebel and a spirited rule-breaker. And she didn’t let anything stand in the way of her dreams. She was a female mathematician, scientist and inventor in a time when women categorically didn’t do those types of jobs.

She was the perfect star for a book to highlight strong, positive female STEAM careers. So I wrote one. And my book became a part of the new movement of children’s books aiming to smash outdated gender stereotypes.

Now the change is thoroughly underway. Authors and illustrators are rebelling – like Ada – to bring women to the forefront. You can pick up biographies of real-life female STEAM figures in any bookshop now, from Women in Science by Rachel Ignotofsky to Fantastically Great Women Who Worked Wonders by Kate Pankhurst. These books celebrate lots of current and historical women in STEAM – perfect for showcasing the volume of women and the volume of career paths in the field. They encourage interest, show role models from all over the world and all walks of life.

Books focusing on one woman at a time, for example Grace Hopper: Queen of Computer Code by Laurie Wallmark and illustrated Katy Wu, or Joan Procter, Dragon Doctor: The Woman Who Loved Reptiles by Patricia Valdez and illustrated by Felicita Sala, start off with the featured woman’s childhood, showing how they became interested in whatever their job became. This is so important for children to identify with the women as children at their age. They can recognise similarities between themselves and the protagonists. They can see that a job in STEAM is accessible and achievable.

Fiction books are making up for lost time too; Rosie Revere Engineer and Ada Twist Scientist by Andrea Beaty and David Roberts, Izzy Gizmo by Pip Jones and Sara Ogilvie, and Look Up! by Nathan Bryon and Dapo Adeola all feature girls aspiring to work in STEAM roles. And they all have sweet, positive and inclusive messages at their core.

Each woman featured in each book represents a possible future, a positive role model, a dream. And it’s not just all about the job they hold. All these characters – both real and fictional – all have a certain drive and zeal to them. To bring it back to Ada Lovelace, what I think makes her such a significant figure for children to learn about is her personality. She was so headstrong, determined and passionate about what she loved, and didn’t let anything – society, the patriarchy, the times she lived in, her own health issues – stand in the way of her need to learn and explore math and science. She knew what she wanted from her life, she went out and got it, and she didn’t care what other people thought.

She and all these other characters celebrate women in science everywhere, and are amazing symbols for STEAM. But equally they are amazing symbols for children to know that it’s okay and that it’s encouraged for them to follow their dreams. Whatever they may be and despite what hurdles they have in their way.

And they shout to the world that it actually is very cool to be a girl, and extremely cool to be a girl in STEAM!

I would be remiss not to mention the next change we must make in children’s books: diversification of characters. Our fight for more women in STEAM in children’s books isn’t over, but we must add some energy to create more change here, too. This topic really requires its own blog – or indeed its own entire book – but I will just touch on it here.

According to a 2018 study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the representation of characters in children’s books is shockingly far from equal. The study showed that characters in 2018 were 50% white, 27% animals or objects, 10% African/African American, 5% Latinex and 1% Native American/First Nation.

In UK publishing in 2018, the Centre for Literacy Primary Education reported an “increase in books featuring a BAME character – from 4% in 2017 to 7%” (CLPE Reflecting Realities Report Year 2, 2018). But this slow creeping up of percentage is simply not good enough. It doesn’t reflect the children reading these books, and a wildly high number of children can’t see characters that share their ethnicity or cultural heritage.

I can’t find a study that splits this reporting of characters into fiction and non-fiction, but after a self-study of my own bookshelves and online bookshops, I believe that the non-fiction picture book side of things is progressing a little quicker (although still not as quickly as it should be). As I argued before, women and girls need to see themselves reflected in strong, passionate and interesting characters. The same argument stands here. Children need to see inspiring non-fiction books about strong, amazing people who look like them.

We need to highlight more minority women in STEAM! We should be aiming for a world where every child in empowered and encouraged through reading to be whatever they want to be.

If you’re not an author, an illustrator, an agent or a publisher, you might be thinking, “this is all very well and good, but I can’t personally make a change in this field”. But you can! You – as the consumer – can change the market! Be conscious of the books you are buying for your children (and for yourself!) – of who they are by, and who they are about, and what they are about. Publishers release books based on what people will buy; we can all influence this by what books we consume.

We need to do better, and we need to do more, and we need to make that change now.