For the month of May, Lifeology is running an open science communication challenge, challenging you to make your own science comic around the theme “smaller than the eye can see!”

This challenge is intended to help anyone, from scientists to people who just love science, from writers to artists, improve their visual communication skills and explore how science and art can work together. You can participate, regardless of your drawing ability, by completing our comic challenge template here and e-mailing your comic to Lifeology@lifeomic.com!

Maybe you’ve started this challenge, but you are struggling a bit – how does one make a “good” science comic? Or maybe you are intrigued by the challenge but you don’t know how to start.

On May 1, we held a live Q&A in our Slack workspace with science comic creators and experts! They gave some great advice for getting started with comics. I’ve curated their responses below. Happy learning!

Be sure to submit your own science comic for our challenge by May 31 – there’s a prize for our favorite entry!

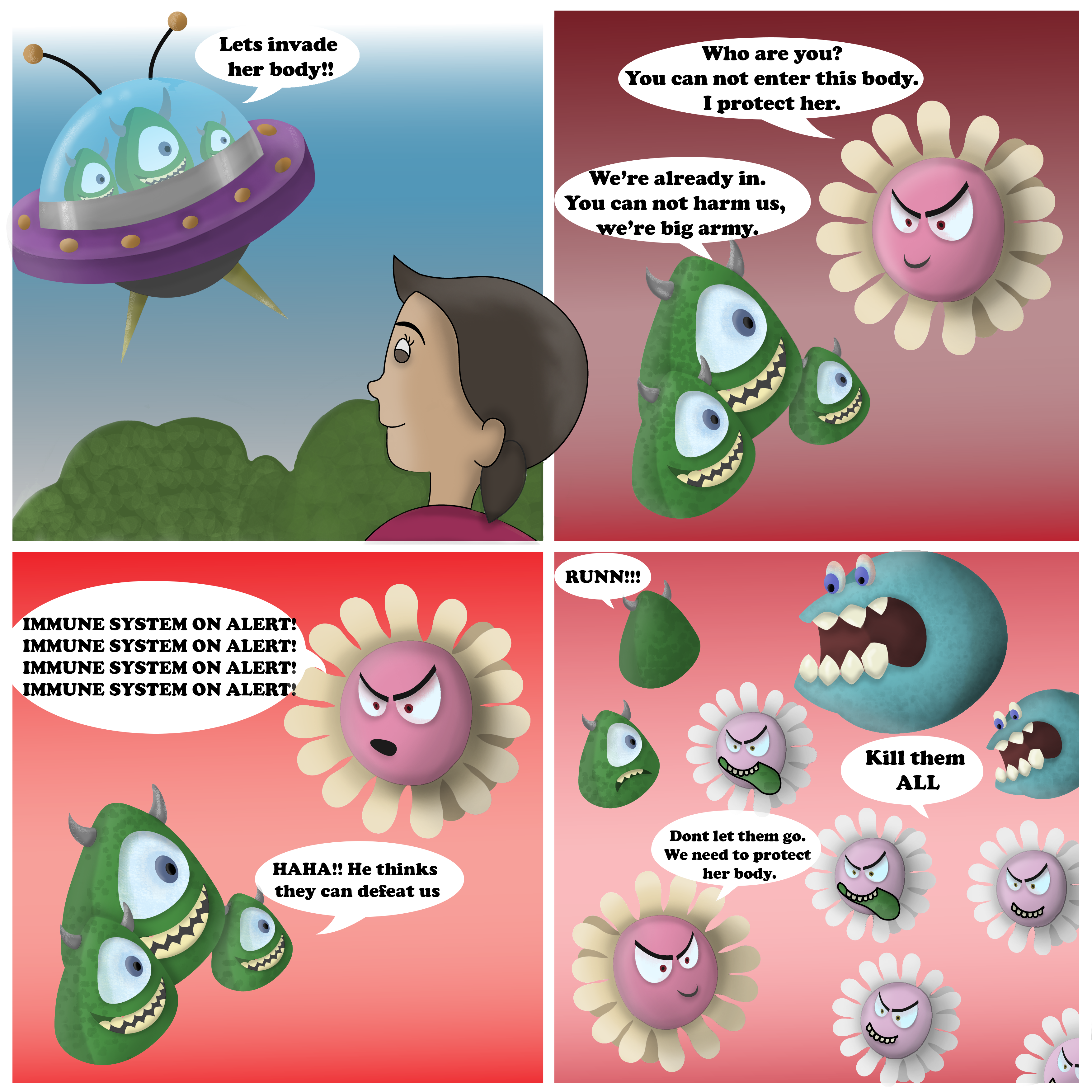

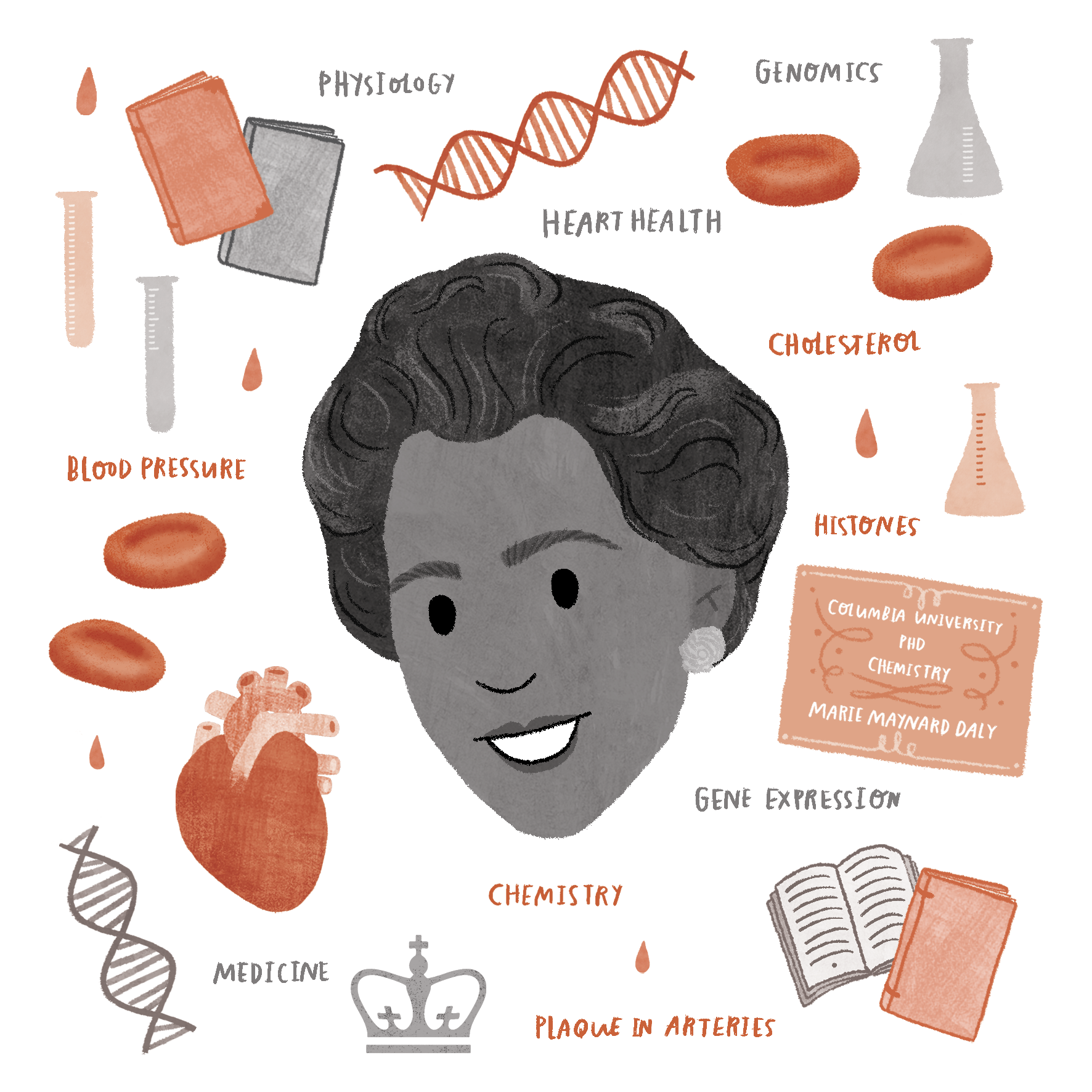

Some comics that have been submitted for the Lifeology SciComm Challenge so far!

Q: What is a science comic to you? How did you get into making science comics?

Abrian Curington: To me, a science comic is any non-fiction comic with science as the subject! I personally count fiction comics that use accurate science, but wouldn’t call them “science comics” specifically.

The proper definition of comics (can be defined as simply “sequential art”) in general is pretty wiggly, so it covers a pretty wide swath of possibilities. Which means more fun for us! But when I think of a comic, I generally think of a series of images that link together in an understandable way.

Echo Rivera: To me, a science comic is a multi-panel illustration of a scientific topic or content. (Panel = squares / scenes). I’ve been creating comics and cartoons for my own blog and love making them. I also come from a research background, so scientists/researchers are my audience – it just made sense to start getting into science comics!

I think comics are special because they involves multiple senses and the combination helps us understand the content better than if we only see a visual (no text) or only read text. The combination really helps.

Matteo Farinella [he has published research papers about science comics!]: Yes, at the most basic levels comics are just ‘sequential art’ – so even Lifeology courses are a great example! I like this flexible definition because personally I don’t think there is anything “special” about comics. Actually I think their main strength is that they combine the advantage of writing, art and diagrams in a single format!

In general for me comics are an incredibly effective way to communicate science, regardless of age, background and education of your audience.

Q: To you, what are the elements of a great science comic?

Echo Rivera: A great science comic should make the reader feel some type of emotion and connection to the material. Whether that’s a laugh through humor, or excitement through new understanding.

For me, I really like to use humor and hyperbole. Making people laugh is a great way to get them connected to the comic emotionally and in a positive way.

Abrian Curington: Totally agree! Emotion is how we make the information mean something to a reader. Also of high importance: A clear “theme” or single point that you are trying to make, demonstrated and debated with clear visuals.

All effective communication is about clarity.

hat are some ways that you can incorporate emotion into your comic? You can do this through expressions of your characters, through colors, through dialogue, and also through the story itself.

You can list facts about microplastics, or you can tell a story about the ocean communities that it is affecting. Attach a fact to a relatable story. Then add pictures.”

Matteo Farinella: Agree! Emotional engagement is the goal. There isn’t really a formula but for me it has something to do with the balance between words and pictures and how they complement each other.

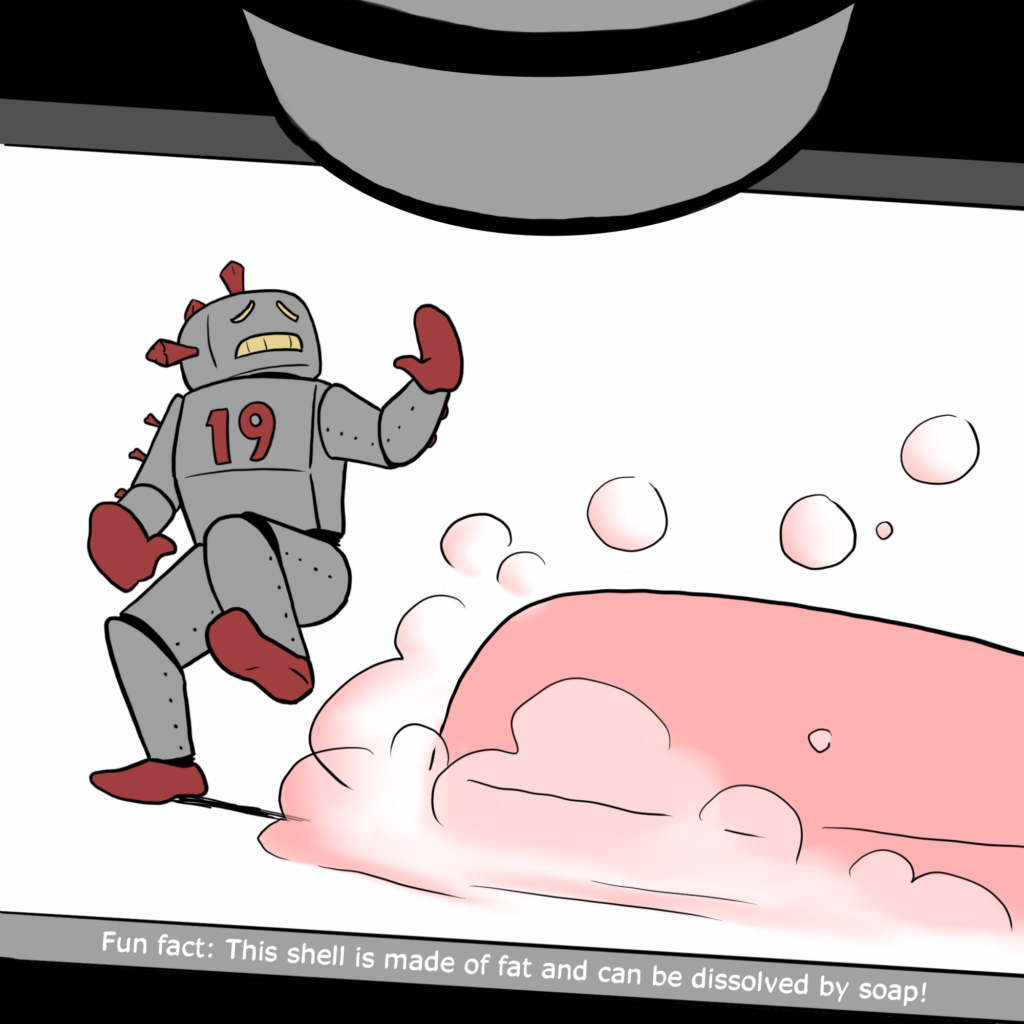

A panel of a comic about “coronabot” and what it does in the human body, by Abrian Curington!

Q: Where should one “start” when making a comic?

Echo Rivera: My first tip is don’t get hung up on whether you have “enough” drawing skills or the “right” software to do it. You can make comics with just about anything and even some stick figures.

If you have a blog, or want to start one, that’s a great way to get going with your comics. You could write about a science topic and then create a comic to use as the visual for your blog post. Don’t have/want a blog? Then consider being a guest blogger (for Lifeology perhaps!) and do a comic for that!

You could also just create comics and post them on social media – I’ve seen those too. You don’t NEED a blog post to go with it!

Abrian Curington: The problem with comics is that there’s SO MUCH to learn! So the best way to get better at sequential storytelling (comics) is to make comics.

Even if your first one isn’t very good and takes you a month, you finish it, then make another. It will take less time and be better the next time. But you HAVE TO FINISH. There’s a magic to completing a comic. You won’t level up nearly as fast unless you finish.

Oh, and also keep your first project as small as possible. Our challenge [here’s a template] is a great start! Make many one-pager comics before moving up. A lot of people like to start with an epic opus. That’s a recipe for disaster on many levels!

Matteo Farinella: As in everything, the best way to learn is to practice (and also read comics and copy comics a lot!).

As Echo says ![]() another thing I love about comics is that the barrier for entry is very low. They don’t require any special software or tools. They are easy both to read and to produce. It’s a very democratic medium and I think this is reflected in the amazing comics community.

another thing I love about comics is that the barrier for entry is very low. They don’t require any special software or tools. They are easy both to read and to produce. It’s a very democratic medium and I think this is reflected in the amazing comics community.

If I had to give more concrete tips I think the most important one is to start SMALL. I love comics but they are a very time-consuming format. I think the most common mistake for beginners is to overwrite their comics, which means you either end up with a epic graphic novel (that you will never finish) or with way too many words per panels. [Abrian shoots for under 15 words per speech bubble, usually hitting under 10.]

Other tips:

- Pick a simple concept you want to explain.

- Keep your text as short as possible…

- … then CUT even more! Everything that can be conveyed in the drawings doesn’t need to be in the text.

- ‘Show don’t tell’

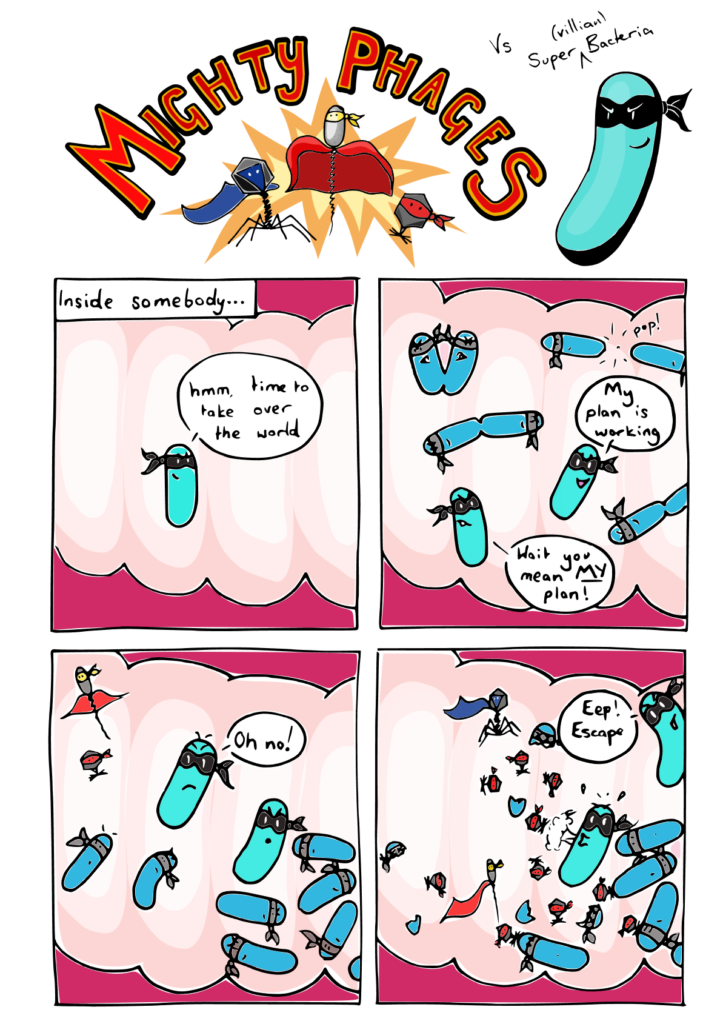

Might phages. by Dr Ellie Jameson, University of Warwick.

Q: Why do you think comics are so powerful for communicating science?

Echo Rivera: We immediately understand the format, it’s easy and intuitive. It’s a story format, and humans love stories – stories resonate emotionally and teach us material in a deep, long lasting, and memorable way. It removes barriers to learning.

The combination of visuals + text is an effective way to learn material.

Abrian Curington: The more senses you can trigger, the more information a person will remember. Comics engage converting text to meaning, converting a single image to meaning, taking several images and finding a link between them, spatial reasoning… the list goes on. But in a clear comic, the reader isn’t aware that they’re doing all these mental gymnastics!

Matteo Farinella: Once again, agree with the importance of “storytelling”. To add to that I would say that explaining science often required both text and pictures. The problem is that in most scientific texts, the figures have become almost completely illegible and – to make things worse – they are kept separate from the text.

Comics are just a way to bring the two back together. Adding some characters and useful metaphors to the mix.

I think sequential art (aka a comic) is valuable because it focuses the audience’s mind. It is so easy to get overwhelmed with scientific information; sequential art guides the reader/viewer to avoid this overwhelming feeling.

Q: Comics involve storytelling – but what IS a story?

Echo Rivera: A story has a beginning, middle, and end. There is often some form of challenge, struggle, confusion, or conflict which is usually the middle part. There also need to be consequences to actions (otherwise it’s just stuff that happens — as a character in the last season of Castle Rock said!)

Telling a story visually means you need to add background elements, facial expressions to use as elements in the story. For example, instead of specifying how much time is passing, you can include a clock with the time in the background. [“Or change the lighting!” – Abrian]

One of the key elements of story, according to Lisa Cron, is showing a character facing a struggle and then showing what the character learned as a result.

Matteo Farinella: Oh, this is a really good question! I want to add something…

Beginning – Middle – End is often quoted as the most basic structure of a story, but that doesn’t necessarily make a story engaging. I think another important element is to have a conflict (or struggle, especially an unexpected one). I think humor works in a similar way too: it’s something unexpected.

Formulas can only take you so far, but one that I often suggest people start with is the ABT.

[…] AND […] BUT […] THEREFORE […]

If your story is just AND … AND … AND (a string of facts or descriptions or unrelated events) it’s probably not going to be very rewarding for the reader. You may think science doesn’t fit this formula, but it’s surprising how many scientific papers you can summarize like this!

[We knew this thing] AND [this other thing] BUT [we don’t know know / how they are connected] THEREFORE [we did an experiment… and here are the results and something expected we learned!]

You could keep going with this structure to bring a human element to science – THEREFORE we did an experiment… BUT something went wrong… at first we didn’t know why, BUT then we realized we hadn’t factored in X or thought about Y! THEREFORE we now think very differently about this thing…

Q: What are some tools you use for making your comics? And how can scientists collab with artists to make them?

Echo Rivera: I started by using Keynote and PowerPoint. I’ve also used Adobe Illustrator and Affinity Designer. I’ve also used Microsoft Paint and built-in drawing apps.

Also I wrote a blog post on how to collaborate with an artist, as a scientist!

Abrian Curington: I use good ol’ pencil and paper with ink. I’ve used watercolor for color, and I will also work digitally with a Wacom Cintiq and Adobe Photoshop/Illustrator, or Procreate with an Apple Pencil and iPad Pro.

If you want to collaborate with an artist, you should start by finding an artist whose art you like, then asking them to work on your project with you! It really is that easy. You should know, though, that just like research (which is one of the first phases of art, we actually follow the scientific method rather closely), art takes time. So don’t ask an artist to create an illustration for you for tomorrow. Think of how long it would take you to write a research paper.

Also, be prepared to pay! Different artists have different rates, but think about it this way, a work week is 40 hours. If it takes a week to make and process the paperwork for your project, multiply that by a living wage for your area. That’s how much your artist would like to make, whether they actually charge that, or less.

Matteo Farinella: I also started using Procreate more and more (for practical reasons) but I started with old fashioned pens and paper and I think that’s the best place to start if you’re new to this. It forces you to focus on the storytelling, without getting bogged down into the technical details.

Also, in general my process consists of 3 stages:

1. SCRIPT: narrow down the text and figure out approximately how many panels/pages it’s going to require

2. STORYBOARD: quick thumbnails for each page. Rough sketches force you to focus on the big picture.

3. FINAL ARTWORK: actually draw the finished thing (the most time consuming part)

Some useful advice for scientists collaborating with artists: Give as much advice as possible at stage 2 (storyboard). Don’t worry about hurting the artists feelings! If they are smart they really didn’t spend much time on this and everything is still easy to change. Better now than later. Any changes will require twice as much time (if not more) after the FINAL ARTWORK.