We just published a new Lifeology course that is a follow up to our illustrated Coronavirus primer, that will help you to better understand this tiny infectious agent. This new illustrated story covers how the virus works in the body, how the immune system fights back, and what people can do to protect themselves and improve their immune health.

We also created a kid’s comic version, illustrated by Abrian Curington!

The course is written by Shauna Bennett and Signe Aasberg at NTNU Norway, illustrated by Elfy Chiang in Taiwan, and reviewed by Dr. Leonard Calabrese at the Cleveland Clinic, Kylie Belchamber in the UK and researchers at NTNU. It is also open access under CC-BY-SA.

In this blog post, Shauna and Elfy dive into the creation of this visual story – read on to learn more about the beautiful watercolor illustrations Elfy created to make this impacts of this virus clear without being scary, and how we collected the information presented!

“The mix of simple shapes and translucent colours was my way of expressing my personal take on the microscopic world inside of our bodies. To me, it’s an abstract world full of mysteries and possibilities with so much going on at the same time.” – Elfy

Writing “What does the coronavirus do in my body?”

By Shauna Bennett, PhD

Planning and writing the first course about coronavirus (on “what you should know“) was relatively easy. We based it on commonly asked questions and misconceptions. For this second follow-up course, we wanted to answer more specific questions about how the virus causes symptoms and why manifestations in the body may be different depending on the person.

I was excited to write about the nitty gritty biology, even though I knew it was going to be messy finding the latest, credible information about what actually happens during a specific SARS-CoV-2 infection.

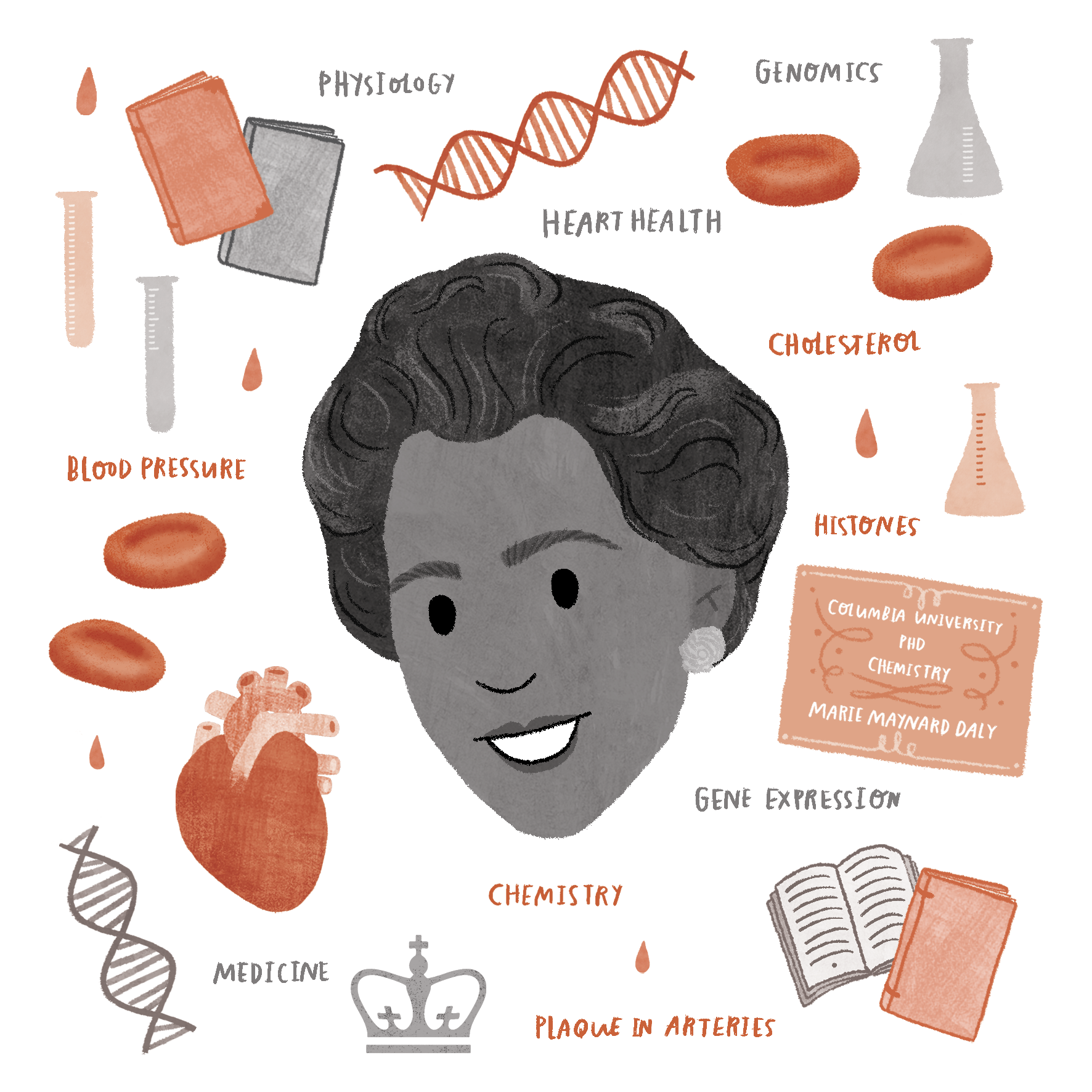

Elfy’s antibody illustration

In a normal situation, if I wanted to write about how a virus causes problems in your body, I would write about a virus that is well-studied so I could be as accurate as possible – and so I could say things like, “this rarely happens”. I would go to the scientific literature and read a review paper to get a general understanding of what occurs. Then, I would find a more specific review papers published within the last couple of years to support the subjects I wanted to touch on, making sure that there was some solid scientific consensus on the matter.

So, writing about COVID-19 was a lot different. With information still so minimal about this virus and what it does to the body, we had to ask ourselves: how quickly do we want to get this course out? Should we wait until we have more solid scientific information? Data is always under scrutiny and reconsideration anyway… And how much detail do we include? Do we talk about rare complications? How much should we worry about scaring people?

After wrestling with these questions, I had to decide where to *find* the information. There is a flood of information from all over, but much of it without peer review – such as interviews with scientists in news outlets, and editorial pieces, and articles in journals I’m familiar with, and discussions among experts on Twitter…. It was a very different information landscape than I was used.

I decided to go rather general with the content, discussing what all viruses do in your body, and discussing the normal responses that we know to happen. Some of the scientific literature I relied on was based on previous coronaviruses, like SARS-CoV. Since scientists have the genetic sequence for SARS-CoV-2, we know some of the ways that COVID may be similar to SARS. From clinical observations, we also know ways that it differs.

I used information from interviews with coronavirus scientists that I recognized to write about the more speculative descriptions. Since our course is meant for a general audience, we decided not to go too in-depth and we covered what we thought to be important topics being discussed in the news, such as antibodies and cytokine storms. Overall, I really hope that this course helps people to understand the complicated role that the immune system plays in the course of a virus infection, and helps to ease some of the fear of the unknown.

Illustrating “What does the coronavirus do in my body?”

By Elfy Chiang

This course is unique in that it focuses on what happens inside of our bodies on a microscopic level – the interaction between viruses and our immune system where many cells and proteins are involved and have a complicated relationship with each other. So at an early stage of illustrating this course, I decided to create a ‘handmade’ visual style including minimal details, something different from the well-rendered digital art often used to visualize cells and proteins.

Pictures of cells and proteins often show the desire to communicate accurate details by including drawings of cell organs or using complex shapes to show protein structures. However, in a course like this one targeted to a broad audience, those details could seem irrelevant and distracting or could even cause confusion. So I decided to go the direction opposite of ‘detail and accuracy’ and decided to use simple geometric shapes to represent the cells and proteins involved in this course.

The simple shapes are like symbols that readers can easily remember, and they can quickly see at a glance how the different cells and proteins. that the shapes represent interact whilst they read through.

As for the medium, I decided to use watercolour to create drawings for the ‘handmade’ texture. One reason for this was to distinguish this art from well-rendered digital graphics often used for cells and proteins, in the process. adding a sense of warmth to make the course more approachable.

Another reason was to create a different visual world separating the microscopic world from the ‘reality’ where characters from a previous course can be seen and were illustrated in a different style.

I also wanted to take advantage of one of watercolour’s special features, the bleeding of colours, to show infection of cells and inflammation caused by the fight between the immune system and the virus.

The mix of simple shapes and translucent colours was also my way of expressing my personal take on the microscopic world inside of our bodies. To me, it’s an abstract world full of mysteries and possibilities with so much going on at the same time.

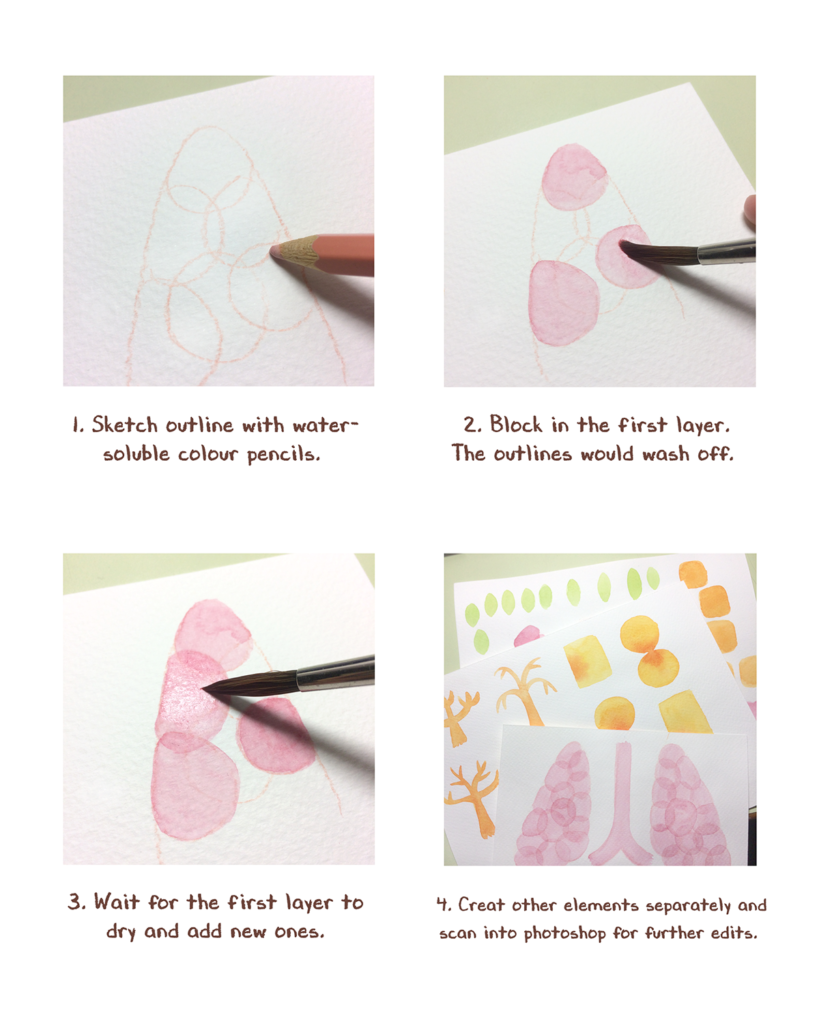

Below is a little step by step process on how I created the watercolour illustrations for this course. I used the wet-on-dry technique to create the transparent shapes of the lungs. I first used water-soluble colour pencils to sketch some outlines. This can be done loosely as the pencil lines can be washed out by watercolour. I then blocked in the first layer of very light paint of shapes. After the first layer dried, I blocked in new shapes where they overlap with the first layer and did the same with more layers after previous layers dried.

For the other elements, like the tree trunk and leaves, I painted them separately and scanned them into photoshop to build the final illustration.

Elfy’s drawing process for the course

What I found challenging with this course was finding a way to show strong and weak immune systems. I thought this was important to visualie because they are key ideas in this course.

Aging is linked to a weak immune system here, so I started to look for ways to show time passing of a living organism. At first, I thought of flowers blooming and withering. That idea finally extended to trees, where I thought that I could use the branches to look like a person with strong arms to depict a strong and young immune system, whereas branches hung down for a weaker and older one. The leaves falling off in the drawing of the damaged lungs can also be a way of showing that the lungs are deprived of oxygen. I’m not strict with how the trees should be explained here and I think they can provide readers with a potential of imagination on how they like to see it, but at the same time, I think it still delivers the message at these parts of the course.