For the month of May, Lifeology is launching our inaugural #SciComm Challenge, a monthly fun challenge that scientists, science writers, artists and anyone else can participate in to improve their science communication skills in a variety of formats!

This month, your challenge is to create a simple science comic (4 square sequential panels) around the theme “Smaller than the eye can see!”

What is a science comic? It is a “narrative form consisting of pictures arranged in sequence”. The pictures might be separated into different panels or involve a sequence of events or dialogue within a single panel “strip” – See an example here.

Want to learn more about science comics before you make your own? Join the Lifeology team and expert science comic creators Matteo Farinella, Echo Rivera and Abrian Curington on Friday, May 1 at 10am Pacific / 1pm Eastern for a Q&A and live chat on science comics! Join the chat in the #scicomm-challenge-of-the-month channel within the Lifeology Slack Workspace. Join the Slack workspace here and then navigate to the chat channel here. Submit your questions for our experts ahead of time – e-mail Lifeology@lifeomic.com.

Need some help setting up your comic? Download our template below!

Submit your comic to Lifeology@lifeomic.com by May 31, 2020!* Your comic will be featured on the Lifeology blog. We will also reach out to the creator of our favorite entry to translate the comic into an open-access interactive Lifeology course (with complementary professional illustration as an option) for free!

See an example of a comic-themed Lifeology course here.

*Are you into digital art? You can send us your comic in digital files like pngs or jpgs (ideally separated into 4 square illustrations at least 1000px X 1000px large, one for each comic panel). Are you new to this whole digital art thing, or art period? No problem! Just sketch your comic out on a piece of paper, scan or take a picture of it, and send it along! Stick figures welcome!

Why a science comic?

Tweeting, a comic by Raymond K. Nakamura, Ph.D.

Science comics incorporate many elements that are great for science communication. They incorporate storytelling, visuals (and often visual metaphors), dialogue, emotions and often (but not always) humor. These elements have been shown (through scientific research!) to improve people’s understanding, interest, enjoyment, engagement with and real world application of scientific and health information. The great thing is that good comics can do all this without feeling condescending or “dumbing down” the science, and can be very accurate in conveying scientific ideas, concepts and facts.

Science comics can work across a range of scientific fields and communication goals. Science comics (reading them or even collaborating in making them!) can help people approach, better understand and feel more personal control over heavy topics such as cancer, as well as grasp what can be very abstract concepts like nanotechnology and physics.

“The ideas that they explain are complicated, but by simplifying them down to the core messages and by providing simple visual analogies, the comics educate and engage the groups that other media cannot always reach.” – Ten simple rules for drawing scientific comics

Not only are science comics great for broad audiences, but they are great training for you.

Whether you are a talented artist or, like me, you can’t draw anything but stick figures, developing your own science comics can help you become a better science communicator. Even if you don’t learn to draw from developing science comics, you will likely learn how to convey science concepts and ideas and findings more conversationally! (Because if you are writing dialogue between characters in a comic, they can hardly sound like they are reading a scientific paper, right?!)

“An effective comic can communicate difficult ideas efficiently, illuminate obscure concepts, and create a metaphor that can be much more memorable than a straightforward description of the concept itself.” – Ten simple rules for drawing scientific comics

For scientists, learning to make science comics can help you to better communicate your research to broad audiences and other scientists alike! You can use them to create graphical abstracts and summaries of your research papers that will increase their shareability on social media among your peers. You can use them in your presentations and talks to entertain your audiences and get lots of information across clearly and quickly. You can use them to engage your students and the broader public.

This doesn’t mean you always need to create science comics all by yourself. You can write and storyboard your comics and then get a professional artist to create the visuals with you! This will greatly boost the impact that your comics can have. But the first step to creating science comics around your work collaboratively with an artist is learning the basics of comic creation yourself!

The magic sauce of science comics – storytelling!

I got into the idea of developing science comics as soon as I started developing Lifeology courses. In many ways, they are similar to science comics. They combine visuals and short text in a “flashcard” format that could be likened to a comic panel.

I realized in writing Lifeology courses and in seeing them illustrated that it is very important to have the “flashcards” relate to one another and flow today in a clear and meaningful way. In other words, they are best connected by an overarching story and characters (like the girl and her brain in this course). It’s somehow easier to see when this is missing in a flashcard format, which can appear disjointed without story and characters, than in the blog post format I’m used to writing.

Lifeology cards are ideally connected to one another via story, so that viewers not only understand the content but are drawn to continue down the learning path through a series of cards. Since viewers are also only seeing one card at a time, it’s important that each card relates to the one before it and after it, and doesn’t seem to come out of nowhere without context. Each card should also advance the “story” in some way, or provide details in context. And then even within each card, it’s best that the text and the visual complement one another and add meaning to one another.

Very similar “rules” apply to science comics! Textual and visual storytelling are key.

“A good comic, like a good scientific manuscript, tells a story. Like a story, a comic has a beginning (the setup), a middle (the conflict), and a resolution (the punchline).” – Ten simple rules for drawing scientific comics

Ready to make your science comic? Here are some tips!

For this month’s Lifeology SciComm Challenge, we’ve given you a broad theme for constructing your comic around – “Smaller than the eye can see!”

You can interpret this theme in any way you’d like. Perhaps your own research deals with objects or creatures that are “invisible” to the naked eye that you want to help broader audiences understand. Or perhaps you’ve been wanting to help people understand how scientific instruments work that let us see microscopic and even nanoscale objects. Or maybe you might even create a comic about how human (or other animals’) eyes work!

Whatever you choose, consider the following questions when you are brainstorming and sketching your comic:

- What will the main message or take-away learning of your comic be?

- How can you commit fully to your main message and have it pervade each of the comic panels?

- Who is your target audience for this comic? What do they already know about this?

- What “scale” will each of your comic panels represent?

You might want to think about the fact that many visual representations of tiny objects in science don’t give the viewer a good idea of scale or what they are even looking at (microscope image scale bars mean nothing to most of us). And by zooming in immediately on things that are really small, we miss things like context and setting (where in the world is this thing?), size relative to other things we know from our daily lives (just HOW small is this thing?), and other details that might help us to care about this weird looking tiny thing that is now filling up our screen. How can you help give context and meaning to something that people can’t SEE?

- Can you create characters and plot that will help your viewers care about your comic’s message and information?

- What should the characters be saying to help viewers understand who they are, what they are doing, their goals, what their actions mean, etc.?

Feel free to incorporate captions to your comic panels as well as dialogue within them!

- What’s the story? What is the set-up, the conflict/problem, the resolution?

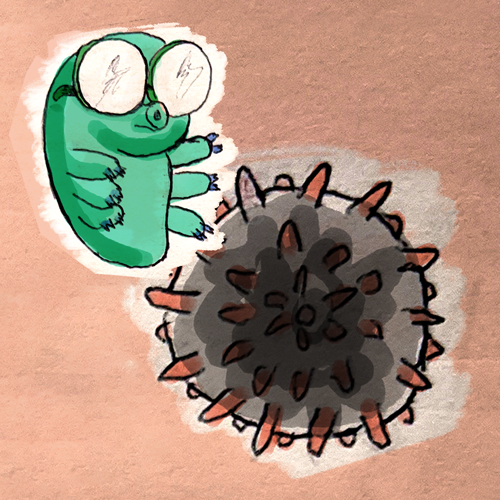

What could give your comic panels a sense of scale? How “close up” will you feature different elements? Coronavirus Needs You, a comic by Gaius J. Augustus.

Other Tips

You don’t have to get fancy – You can use stick figures! The story matters more than the art. But include details that make us care – scene, objects, weather, and other details that might help us understand the characters, their roles in the story, the emotion, the setting.

If you do create an abstract visual, let it complement written content or be there to allow viewers to sense an emotion or mood.

Choose the frame/scale of each comic panel carefully. Have you allowed the viewer to get a sense of where we are, before you drop them in the middle of an action or scene? How can you let scale help the viewer understand important details? Include more “wider framed” visuals (like “long shots” in a movie) to give your viewer a sense of where they are at some point in the comic. This may be especially important for comic illustrations showing what’s happening within the human body at a cellular level, for example.

Ask yourself – Will viewers get your message? How could you better help them get your message?

How will you transition between the comic panels? Will you transition between actions of one main character? Between characters? Between scenes? Between moments of a single action?

Ask yourself if your comic panels flow well together. Split second confusion on the part of the viewer (“Wait, where did this character come from? What is this? Where are we now?”) can break their focus. Imagine seeing a rogue cameraman accidentally move into the corner of the shot of an intense scene of your favorite movie. Your transportation into the story might be temporarily broken. So try to make sure that the panels of your comic build upon each other and flow without raising questions outside of what is happening in the story.

You want readers to understand the information you present, but also to care about it. Help them care with human characters, with intensity, with emotions and sensations. How can you add some intensity and emotion to your comic visuals?

Science Comics Reading and Resources!

Ten simple rules for drawing scientific comics – PLOS One

Microbiology can be comic – a commentary and comic examples!

Science Comics’ Super Powers, by Matteo Farinella

Science Comics: A Creative Gateway into Literacy and STEM – Science Friday

An inside look at the making of a science comic about protecting your hearing! By Echo Rivera and Allison Coffin

Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels, a fantastic book by comic book writer and artist Scott McCloud (at Barnes & Noble)