Photograph of a tablet with a scene featuring Princess Nausicaä from the Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind film. Various science tools and a few plants surround the tablet. Photograph taken by Julia Licholai.

The phrase “princess scientist” feels like an oxymoron for pairing intelligence with femininity. Rarely do bubbly characters have intelligent roles and seldom are girly characters also scientists, but once in a while, television and movie writers dream up something fresh, like Princess Bubblegum (Adventure Time) and Princess Shuri (Black Panther). Growing up, watching these characters helped seed my childhood dream of running my own lab where I would genetically engineer colorful pets. While I don’t currently design pink hamsters, I do wear dresses in a lab every day, pipetting colorless solutions as I wear gloves outlining my assortment of rings.

Intelligent and Stylish–Scientists Can Be Both

I grew up admiring a scientist who lives in a fantasy world created by Hayao Miyazaki, the renowned director famous for creating Spirited Away and co-founding Studio Ghibli. The film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) follows a female character, Nausicaä, as she navigates the political clashes between two cultures: one aiming to conquer nature and another desiring to live in harmony with it. In this post-apocalyptic world, gigantic insects the size of small buildings dominate the terrain. Attempts to tame them or their forest draws the insect army to demolish kingdoms and villages. Coexisting also seems impossible because the ever-expanding forests create thick poisonous clouds of pollen, suffocating nearby residents. With the support of her villagers as a beloved princess, Nausicaä attempts to mollify the foreign commanders as they try to destroy all insects and their habitat with a dangerous ancient weapon. Throughout the film, she dissipates knowledge about the structure and ecosystem of the dreaded forests using knowledge she unearths while studying the plants in her secret underground laboratory. Simply put, Nausicaä is a princess scientist.

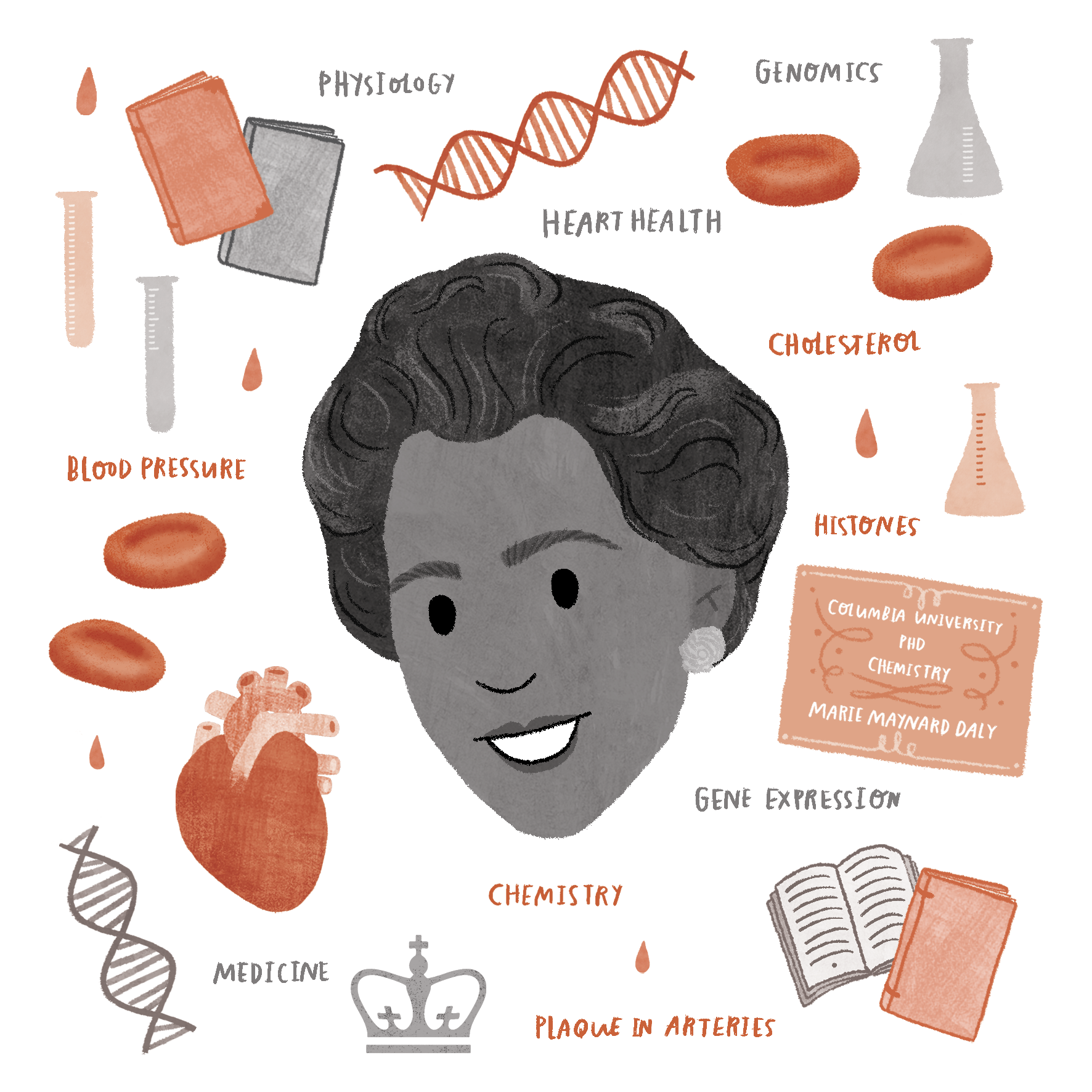

I wasn’t particularly in awe of Nausicaä’s role in helping her people, most strong female characters do so (especially in Ghibli Studio productions), but I admired how she fulfilled her royal duties while also investigating her natural world. Even now, I am impressed by the character’s multidimensional role as a scientist. The stereotypes around researchers are unfortunate, with Hollywood often depicting extremely awkward and obsessive personalities in academia (think The Big Bang Theory). Such specific depictions of researchers can hinder people from entering science, seeing how “The Scully Effect,” named after a female forensic pathologist Agent Dana Scully from The X-Files, is known to have inspired many women to enter STEM. I have even seen a little girl in a t-shirt with bubbly letters declaring “Forget Princesses, I want to be a Scientist.” Sexism exists but linking femininity with foolishness is silly—some notable researchers, like May-Britt Moser and Hedy Lamarr, are recognized for their intelligence while also being stylish.

SciArt to Break Science Out of Its Ivory Tower

Unfortunately, academia has a reputation of being exclusive with who they allow into their ivory tower. To ennoble someone as a scientist is thought to require years of dedicated lab work and a PhD. Naturally, a community built on gatekeeping uses language to distance the “outsiders.” I see remnants of this mindset in the science art communities I inhabit. Often art pieces tend to directly represent their subject matter, not always straying into more abstract or stylized forms. I, myself, mainly represent anatomical structures with great care to portray them accurately in my work. It’s as if loosening one’s ties to science directly jeopardizes an artist’s belongingness in studying the factual, natural world. There are many other factors and possibilities to consider, but I wish that science communities appreciated the imagination and subjectivity of the science-inspired art found in Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

A painting of Princess Nausicaä by Julia Licholai.

Worthwhile science art, or sciart, is expected to be an even blend of science and art. If a piece leans too much into science, it’s more of a scientific illustration but skewing toward artistic creativity diminishes scientific relevance and is “just” art. Yet the art that falls into these sidelines have their own importance, like the life-like medical illustrations by Frank Netter still being used in medical schools. What is less likely to be lauded on the walls of biology buildings are pieces that favor more artistic influences than its incorporation of science. Despite its negligence, these creative pieces are powerful with their ability to influence children to pursue scientific careers and adults to tap into the childlike curiosity that inspires researchers. I like to call these more exploratory pieces “science-inspired art.” This personal category of art includes futuristic styles, performance pieces of EEG signals editing videos, cartoon series about magical science teachers, and anime films about princess scientists. Scientific illustrations educate, but science-inspired art changes the way we imagine, a driver for scientific discoveries.