It’s no secret that artists are often asked to work for “experience” or “exposure”. And even when artists are paid, we are often paid much less for our skilled labor than other professions. While there are many reasons that this issue continues to be pervasive in our society, one reason I see most often with clients is that they don’t know the artistic process. So here I’ll be covering 10 things you may not know about the creative process.

This post is cross-posted with permission from the author. See the original post here.

How long did it really take to create your last scientific figure?

First, let’s talk about your science.

It’s time to publish your next paper, and you’ve created a figure with the key takeaway from your work. Readers of your paper will look at that figure for years to come. A good figure can be digested quickly, maybe in 30 seconds. More complex figures (and poorly designed figures) may be stared at for several minutes (or more, based on papers I read during my PhD) before someone fully understands your message.

How long did it take you to create that figure? Did you output the data using software, creating it in just a few minutes? Did you drop images into Photoshop and take an hour or so to put the figure together?

There’s a common joke I’ve heard many scientists make when presenting their data at conferences and seminars: “This figure represents X years of work.” Let’s talk about what you already know, the background work that goes into a scientific figure.

Things you have to go through before getting that figure done:

- Build expertise in your area of research

- Research current state of knowledge

- Design experiments

- Optimize experiments

- Run the same experiment many times

- Fill in data gaps with results from additional experiments

- Interpret results

- Determine best and most appropriate way to present the data

- Get revisions from others

All of the above is just a reminder that something that seems straightforward and quick actually has years of background expertise and plenty of up front work that goes into it. You already know this. In the scope of the final figure, much of that work may feel “invisible”.

Art (and any creative project) is the same way. The creative process has plenty of its own “invisible” work, and I find the parallels with the scientific process enlightening.

Build an expertise in your area of research

I really began my formal art training at 13 years old, when I started at an arts magnet school. During my time at that school, I spent 2-5 hours every day on arts training. When I continued on to an art and design university, 8-16 hours of every day were spent actively researching, practicing, critiquing (ie, peer review), and learning.

I have 9 years of formal art training under my belt. But just as you don’t stop learning when you finish graduate school, I’ve learned a lot since those days. New technology, new processes, new styles all call for adaptability and a love of learning.

Research current state of knowledge

While, in general, most artists are regularly researching recent trends (whew, a tongue twister), I want to focus on the creative process around your project. The work I create for you doesn’t appear out of thin air. A lot of time and effort goes into it, and the first big point of effort is the research.

My projects all begin with a consultation. Before that consultation begins, I typically do a bit of background research. Depending on the information you give me, I may look at your lab website or twitter account. Once I get a good idea of your research area, I do a scientific search to learn a bit more about the subject and a creative search to see how the subject is currently depicted.

After the consultation, I usually have a better idea of what you are looking for. Then the real research begins. I spend a long time looking into all aspects of the project from researching color palettes to reading literature that might inspire creative ideas.

Once I’ve started on the project, the research doesn’t stop. I regularly go back through my files and make sure I’m still in alignment with my initial conclusions. We’ll get back to this point in a bit.

Design experiments

No, we don’t just sit down and create masterpieces.

Before every project gets started, I sit with it. I create in a broad range of styles, from flat design to painterly. And each project has stylistic considerations as well as time constraints and other logistical challenges. Not planning out a project from the start leads to problems later on.

This part of the creative process can look many ways:

- mood boards (a collection of inspiration)

- color palette guides (semi-abstract miniature pieces that use large blocks of color. These help to hammer out whether a color palette will work, but also how the colors will be used to help with balance and flow)

- sketches (lots and lots of them)

- prototypes

- photo references for textures, shapes, or complex visual elements

- and more….

There is no one size fits all in the art world. Even when we use the same artistic style for multiple projects, we still do a great deal of experimentation to be sure that we can meet the needs of our clients. The research we’ve done and the visual experimentation we do allows us to “design an experiment”, or in other words, to determine the best creative process to produce the final deliverable.

Optimize experiments

In science, even though we design our experiments with the best of intentions, most experiments need some amount of optimization. Whether that looks like writing more efficient code, improving the purification of a protein, or maximizing the yield of an analyte, optimization is incredibly important to the scientific process.

The same is true for the creative process. Every piece of art that I make is a balance between the amount of time I have and the style that I want. So, once I’ve define the visual style for a project, I then spend time deciding the best way to implement that style. That means creating the same (though not always) conceptual images over and over again, and making tweaks to the creative process until I feel confident about the look and time commitment it.

Without this step, it would be difficult to estimate completion time. But perhaps more importantly, without optimizing the process for any given project, I can’t be confident that I will be able to fulfill the high quality that a project needs.

Run the same experiment many times

If you thought that artists just work linearly, creating a piece of art once from start to finish, you are very wrong. From drawing lots and lots of sketches, doing scaled down prototypes, creating models for light, flow, and color balance, there are a ton of ways we prepare for the final product during creative process.

But even when we start work on the “final”, it’s not one straight path. Iteration is just as important to an artist as it is to a scientist. Most of the projects I work on require me to start over in some capacity at least once. Sometimes things that worked well in the early stages just don’t anymore, or we get a new piece of information that changes how we view the project. Sometimes there are technical failures that we have to find workarounds for.

We don’t just sit down and bust out a final piece of art. I wish it worked that way, but it doesn’t.

Fill in data gaps with results from additional experiments

As mentioned above, every project has its challenges. And sometimes no matter how much you plan and how far along you get with a project, additional work is necessary. The creative process has to be flexible to meet these needs.

For example, I was once working on an animation project that required me to make animation-ready characters. As we entered the actual animating part of the creative process, my client and I had a conversation about a particular scene that just wasn’t working.

We decided that the problem could be solved by having a seated character model in several shots, however, I had not designed the character model to be in the seated position. The animation tool I chose for this project meant that each additional pose would take quite a bit of time to create upfront. The client and I agreed that it was worth the effort, and I built the new seated character model, which radically improved the video.

We build this into our creative process because we know that things change as a project develops. Creative projects at some point feel like they take on a life of their own, which is incredibly rewarding. I love this part of being an artist, but it’s definitely something that my clients don’t seem to understand up front.

Interpret results

Part of every creative process (and every good collaboration) is communication between the artist and the client. But with communication often comes the challenge of explaining the jargon on both sides. When the result isn’t what the client expects, it can sometimes be difficult to get across what is wrong. Sometimes it’s because the client can feel that something is off, but doesn’t know the words. And other times, the language just isn’t there to communicate the issues.

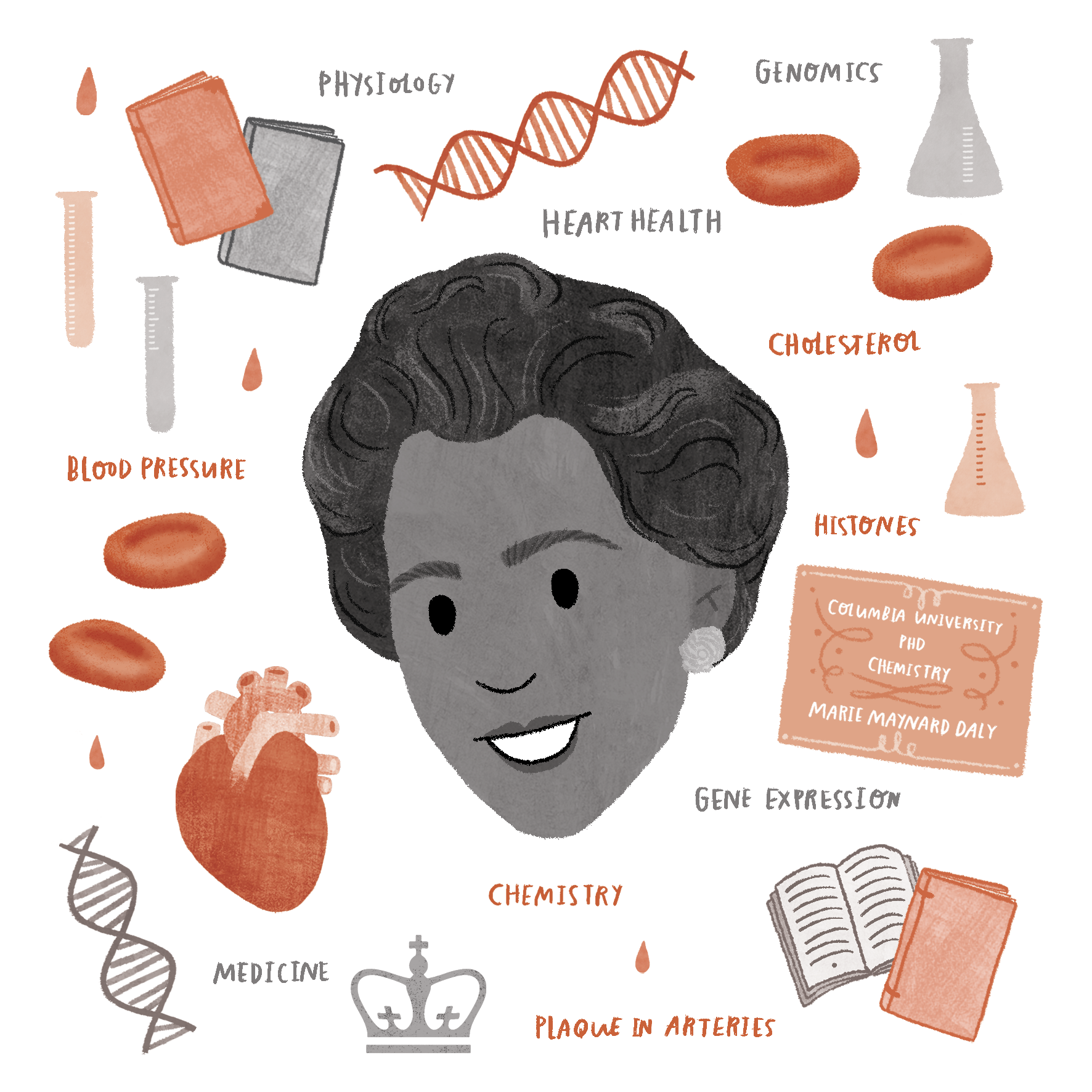

While working on a course about immunotherapy for Lifeology, I received feedback from several reviewers. Each reviewer had their own expertise, and it was important to address all their concerns while also communicating why I made the design decisions I did. The result is a really cool course that I am incredibly proud of!

This is another place where expertise comes into play. We’ve learned through experience and practice how to address these concerns and get to the root of the problem. We know how to offer solutions, and when and how compromises can be implemented. If delays will be necessary, we can create a plan on how to shift and meet a new deadline.

This is something scientists do with each piece of data they get, and it’s something artists build into the creative process for every project.

Determine best and most appropriate way to present the data

This is essentially a point about visual communication and design skills. All that means is that artists have training on how to communicate complicated ideas in a visual way that makes those ideas more digestible. It also means that the audience who views the project will read it with ease.

That doesn’t always mean the most elaborately beautiful images. Sometimes, it means making the information (not necessarily text) so central and fun that the visuals just act as support.

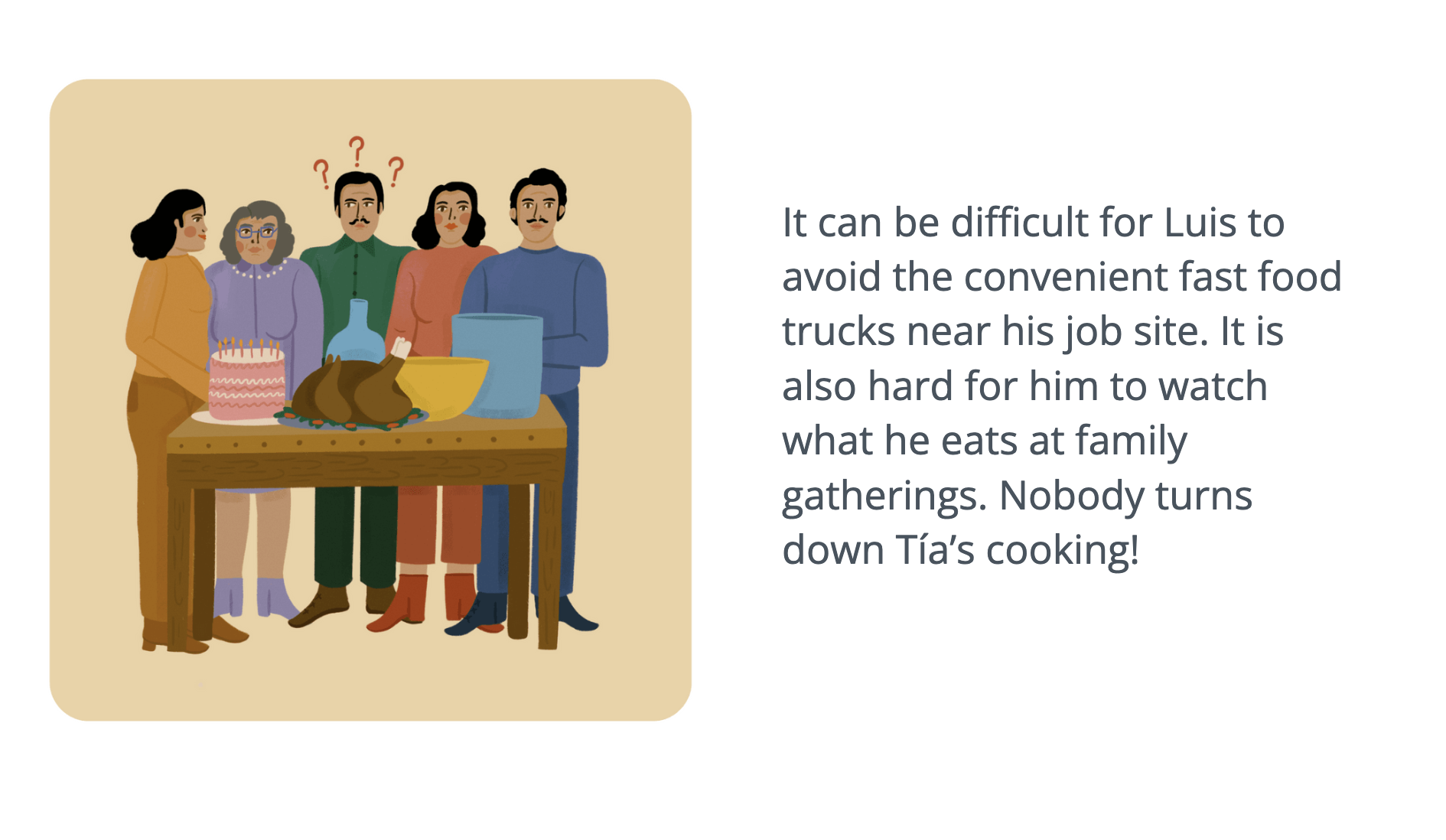

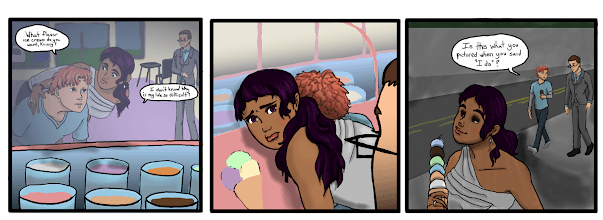

A great example of this is a newspaper comic. Most people who read these comics digest them in a matter of seconds. If it’s a humor comic, hopefully you’ll laugh hard. Maybe you’ll save it for later or share it with friends, who also will take a few seconds to read and laugh. For many of these comics, the art takes a supportive role. The artistic choices that the creator has made enhance the comic, make it easy to read, and allow you to get to the joke and start laughing at a good pace.

FRIEND: “What flavor of ice cream do you want, Krissy?”

KRISSY: “I don’t know! Why is my life so difficult?”

Frame 2: Krissy looks back with big sad eyes.

Frame 3: Krissy in foreground with an ice cream cone with 6 scoops of different flavors.

FRIEND to Krissy’s husband: “Is this what you pictured when you said ‘I do’?”

While this is true for any artist, there’s an added layer of scientific data for SciArt. Understanding how data is structured, the proper way to present that data, and how to represent it fairly and clearly are especially important. While a scientist’s input is crucial for this part of the creative process, an artist familiar with data visualization adds these considerations to their workflow.

Get revisions from others

The peer review process is, in my opinion, one of the most important parts of true scientific process. Whether that’s showing a colleague or coauthors your manuscript draft or dealing with “suggestions” from reviewer 3, this input and inevitable revisions strengthen the work. Getting others eyes on a project can lead to innovation, clearer messaging, and more robust results.

The same is true in the creative process that we use in art. I often run concept art, storyboards, and sketches by my partner (who is also an artist). If the project has a specific target audience or uses a niche skill that I’m still working on (like early in my animation days), I’ll send it off to get input from a friend for review. I also like to hand off projects to non-experts to get their opinion on the jargon and messaging.

But the most important person to review science art is the scientist. The subject matter expert is the person who knows whether a metaphor has hit the mark. They can tell me if the art is inaccurate. And, most importantly, the client can tell me if early concept work is on the right track. There aren’t many things worse than getting close to completion and suddenly realizing that we need to start over.

The revision process is not to be taken lightly. For clients, this is the time to air any issues you have, including ones that are difficult to express. For artists, this can range from making small adjustments to overhauling the project. Revisions are also sometimes like reviewer 3, taking a project out of scope and causing a huge change in timeline and effort.

Clients should keep in mind that artists typically budget their time between projects. Changes in scope (especially late in the project) can mean turning down other jobs, delaying jobs who have already been promised a deadline, or losing another job because you now have more on your plate than you can handle.

It’s not a great place to be in, but it is better than a client feeling that they didn’t get what they needed from the project. You should absolutely bring up concerns and reservations (no matter how big or small), but be aware that there may need to be compromises made in terms of compensation and timeline.

Other quick notes about the creative process

I hope all of the above considerations show you how similar the creative process is to the long process scientists take to create just that one figure for their manuscript. Just like science, art is a long, detailed, and complex process that combines theory, technique, and skill to create a final work of visual brilliance.

For these reasons, I hope it is clear why artists (expert visual communicators) deserve to be paid for their work with more than “experience” or “exposure”. When you pay a post-doc or a science faculty member, you are paying for more than a minimum wage estimation of their time spent. You are paying for years of experience, subject expertise, technical skill, and more.

Please give artists this same respect.

Last but not least, I would like to leave you with a few elements of the creative process that didn’t quite fit in above, but are nevertheless important things to keep in mind.

- We don’t pull designs out of thin air

- The design we show you isn’t the only one we drew

- We have several projects going on at once

- Even a “simple” design can take a long time to create

- We can be nit picky and perfectionists

- Design decisions are made with purpose

- Your feedback makes us think hard about our work (and that’s a good thing)