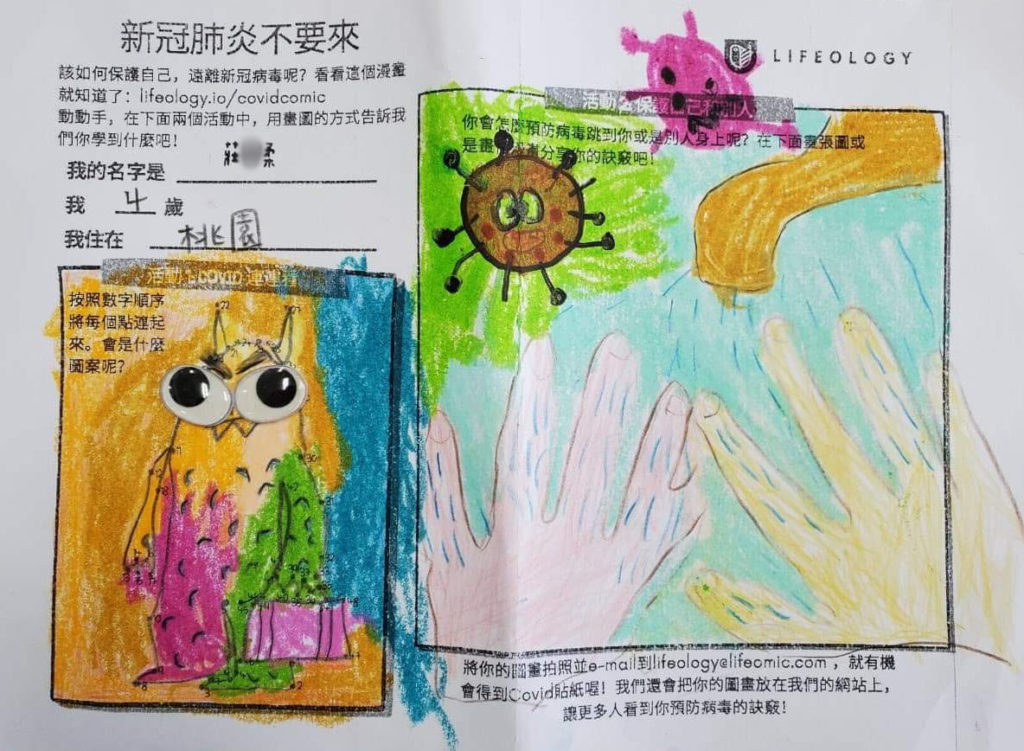

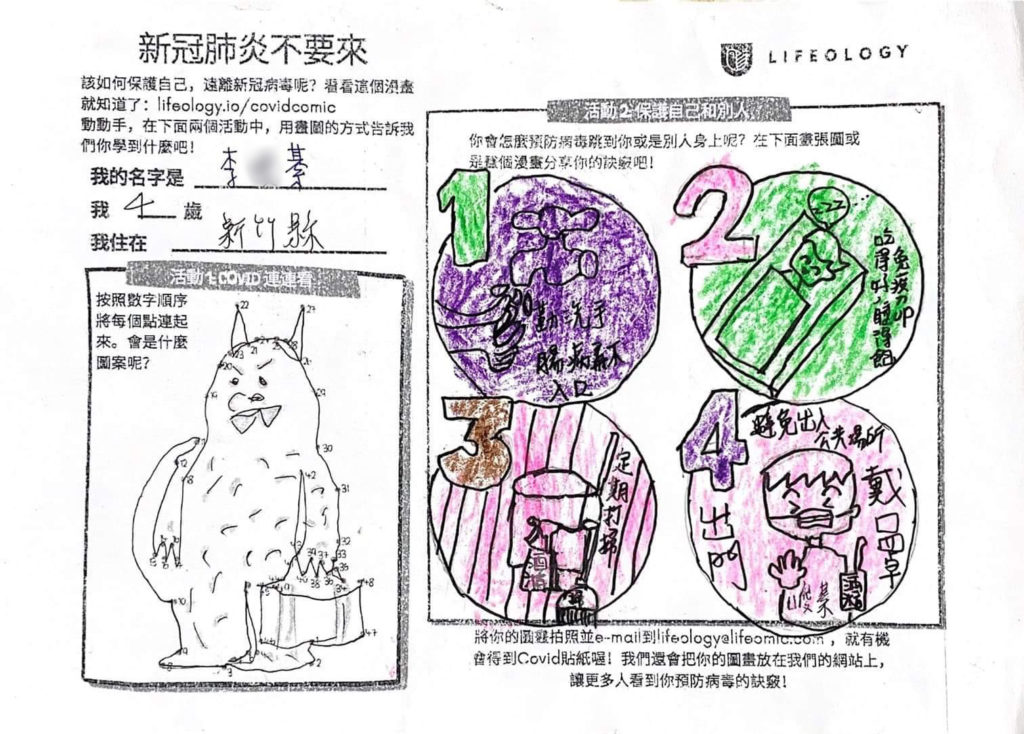

This month, Lifeology is hosting a science communication challenge for the kiddos – draw what staying safe from COVID-19 means to you! We’ve had some fantastic submissions so far, including 70+ drawings from children in Taiwan who completed our drawing/coloring worksheet in class!

A completed “Keeping COVID Away!” Activity Sheet!

Lifeology also hosted a live-chat on our Slack workspace this month about how to talk with kids about science, health and risk. Our chat experts included visual arts K-12 educator Elaine Algarra, science and art K-12 educator Melody Rose Serra, science illustrator and authors of “The Inside Book” (a book about COVID-19 for kids) Matthew Griffiths, science producer Maren Hunsberger, children’s book author and illustrator Anna Doherty, illustrator of the Lifeology “COVID Comic for Kids” Elfy Chiang, and others! We’ve curated below their advice and responses to our questions about how to communicate science with kids.

Q: What do you see as an important goal of scicomm with kids?

Maren: I think the most important goal of science communication for any audience is to answer their questions. That may seem really obvious, but often science communication can barge ahead without considering what the actual questions, currently held beliefs, or misunderstandings of the audience actually are. By having science communication driven by the audiences’ needs (i.e. questions), you can address all of the facets of the issue you’d like to while framing it within their existing worldview(s).

Obviously the questions will vary in complexity based on age, but by letting them ask questions first, you can also see what’s important to them and answer with that in mind.

Elaine: This answer to this question may depend on the age of the audience!

Younger children ask a lot of questions, and science communication can provide them with the resources to quench their knowledge. It can be an exciting way of understanding the world around them. Younger kids tend to be ego-centric and are very excited to learn facts and repeat them. They can apply science communication materials to themselves and real-life to help better understand the world. A goal would be to build curiosity and empower them.

With middle school and high-schoolers, cynicism and coolness can creep in. We can use science communication to help older kids feel like scientists; using real data, and interactive communication would be a plus. It has to be impactful and make meaning in their lives. We need a scientifically literate populace to deal with the world’s problems, where teenagers can develop critical thinking skills while promoting curiosity. Also, we need to get rid of gateways and gatekeepers. Effective science communication could do that.

Matthew: I think inspiring critical thinking and questioning is a big goal. Generating a thirst for more knowledge, and a wonder at how amazing the world is. I think it’s important to also be relatable and deal with feelings (depending on the age group you aim at this would change). Some science could come across as boring without some good relatable storytelling.

Anna: For me, an important goal is to make science seems engaging and exciting, so that the kids (at whatever age) leave wanting to know more and explore science for themselves, whether that is by researching more at home, doing little home experiments, or simply telling their friends about what they learnt on their way home from school. It is important to engage on their level in a positive way, with language and analogies that they can understand from their everyday life. And to make it seem like science is accessible to them, not just for the “super clever” people!

[In terms of how to make science engaging to kids], storytelling can be a big help – a narrative keeps children interested and engaged. But if you don’t have that, try pictures or – depending on the subject – objects or activities they can interact with. This will help them put what they are learning into practical use and/or see it for themselves!

Melody: I just finished teaching Day 5 of Dinosaur Week with kids that are on average 5 years old. I got out of class late because they had so many questions. I think younger children are making connections, for example, “The spinosaurus has a spine like we do, right?” “Did they use it for the same reasons we do?” They are figuring the world out and trying to build those connections, it is so so neat!

Q: How does or should communicating science info look different for kids than for adults?

Matthew: The form of communication needs to be relatable. Finding ways to help understanding through storytelling goes a long way to helping with that. There’s also a thirst for fun facts, some kids love knowing what’s the “biggest” or “fastest”.

Also I remember as a kid being really excited about the actual science things… eg. growing crystals. If there’s a practical real world element then the science is so much more enticing!

Melody: I agree with the relatable piece, the more relatable the more they can build off of the information. I also think that kids are so visual, I was just showing them pictures of fossils of a spinosaurus tail and as soon as I did they were like “ohhh they can probably whip it like aquatic animals!” And I was like “yeah they can, and on that note, let’s look at this new discovery that was made in April of this year!”

Elaine: As a non-scientist educator, I would make sure that whoever is communicating should know the age range, reading level and tone. With kids, we want to reassure them while empowering them. Here is a great short article that uses examples of storytelling and science.

Maren: For children I think one important thing – especially with talking about scary topics like COVID – is to make it as play-based and hands-on as possible. So they get to have fun, learn kinesthetically, engage their imaginations, and so get to feel a sense of agency while trying to engage as many learning pathways as possible.

Anna: Yes I definitely agree with Maren, making something which could be “scary” or is quite a difficult topic to grasp fun and playful is so important. And being very welcoming of their questions about it is important too!

Signe: I also find that kids are not necessarily scared of I expect. I.e. with the COVID cartoon, my daughter (4) is not scared of disease or death, but she is scared of characters who are “bad”. So I try to explain having that in mind.

Q: How can we start to inspire kids and engage them more deeply in science?

A completed “Keeping COVID Away!” Activity Sheet!

Matthew: Something pertinent here is representation – kids need to be able to see themselves and their lives in the stories and the science.

Elaine: Listening to stories activates different parts of our brain. We begin to feel the story and imagine it. What better way to engage young children? They can make connections with narratives.

Anna: This doesn’t apply to every topic you might cover with kids, but if you can, tell the story of the person who invented/discovered/etc. the topic (for example Ada Lovelace when talking about computer programming or Marie Curie with radioactivity). That does two things. First, it helps kids have a person to associate with the topic, which can be super helpful in getting them interested. Also, if you tell the story of that person’s life from when they too were a child, it can make the kids identify more with science and feel like scientific paths are attainable and an option for them, too.

Maren: Letting them retell a story can also be super useful. So presenting the original idea or concept in an engaging way (through play, a story, etc.) and then letting them make it their own in some way. “Tell it to each other” – then they get to experience the science as both the receiver and the storyteller, and that can be very useful in cementing it in their learning pathways.

Elaine [In response to Maren]: Kids also love taking charge! Yes, letting them retell a story, or having them come up with great ideas on how to do things that relate to a story or questions. Try this: If you’ve been talking to a child about COVID-19, ask the child if they have any ideas on how we can stay healthy. My twins came up with washing your hands, trying not to touch your face, eat healthy food, stay 6 feet away and wear masks. They then made a poster to stick on the wall in our bathroom!

Melody: In my free [online] science classes for kiddos, I offer that it’s okay to say “I don’t know, but let’s find out together.” That empowers the kiddo in awesome ways. It makes them feel like adults don’t know everything, also like they are part of the discovery alongside you. They also learn that sometimes it’s okay to not know the answer.

Q: What are some things we should consider when communicating about risks like COVID-19 with kids?

Maren: In my experience, positive reinforcement and affirmation are always better than negative reinforcement. So instead of saying “this, this, and this are bad, and here’s why”, perhaps say “this, this, and this are good, and, here’s why”. Then give praise/reward for completion/repetition of the good behavior.

I think one way to implement this positive slant that can make a topic less scary is not focusing on “the bad thing that will happen if you don’t do x” (for example: people will die). As one of our experts mentioned in a previous thread, young children tend to be very ego-centric, so this could easily turn into an anxiety about being afraid of doing harm to others. Instead, focus on “the good things that will happen when you do ‘x'” (i.e. washing hands and wearing masks means everyone says healthy). With this approach you can still address the important topics and make it feel like a big deal, but not with a big looming threat as the incentive.

Anna: If you do have to mention something in a negative light, give your kid(s) time after the conversation to feel safe, to feel like asking questions is ok, and to feel like if they are scared, they can talk to you about it at any point in the future.

Matthew: This can be tough, and I think quite a bit might lie with whomever is reading with them or there to answer questions or reassure them. It can also be important to learn about risk even if it is scary (we shouldn’t avoid topics). I agree on the positive reinforcement and affirmations.

Elaine: Create social stories and base them on relatable, real-life experiences. Children worry more when they are kept in the dark. Empowering is key. An empathetic tone is essential. Make it fun!

Also, with COVID-19 or other risks, we can direct the child away from the central focus. We can focus on those who help, how they help look after us, and how we can keep healthy; these relate to real-life experience and empower a child.

“My daughter had a fear of using the bathroom and would hold in her poop until it got too much. She was so scared. It was painful, and there were times I felt helpless. So we bought books – “The Science of Poop and Farts,” books, that gave her an insight into how her body worked in a fun way. We would read them together, and she felt removed from the center of the problem emotionally, and it helped her to get over that hump. We sat in the bathroom and made songs up about what we had just read.”

Card from the Lifeology COVID Comic for Kids.

Q: How simple is too simple in terms of explanations and art?

Anna: I am not a scientist, but I think it’s better simple and you can build on it, than too complicated to begin with. For example, when you’re in first grade you learn plants need water to live, and by high school you know WHY the plants need water; so you started with the simplified version and built on it as you understood more. I think, so long as it’s not losing the essence of what you’re talking about, really simple to begin with is good!

Maren: This is definitely the most classic question in all of SciComm! There’s not one easy answer – it’s completely audience dependent. So my best advice is to get a really deep understanding of your audience: their education level, their existing understanding of the topic, their common questions and misunderstandings, etc. Then you’ll have a much better idea of what is appropriate.

For example, videos that I make on my personal YouTube channel are aimed at an audience that has a maximum high school level science education. I avoid using any jargon at all and load up on the analogies. The videos I make for Lawrence Livermore tend to be consumed by a more subject-niche expert audience, usually with post-graduate level science education in the topic at hand. So I’m going to use more technical terms that they’ll be familiar with, so they don’t feel alienated and talked down to.

Q: What communication formats are particularly appropriate and engaging for kids?

Elaine: Younger children enjoy hands-on and coloring tasks. Cut and paste content could be fun – sequential storytelling. Have them use visuals to tell/retell the story! In the past, I’ve had students produce “How to” Zines (examples here and here) – this format is useful for a wide range of ages. My 7-year-old twins enjoy zine-making, as do the high school students in my art classes. I’ve also successfully used this format with students with ASD during the pandemic. One student created a zine on “How to Social Distance.”

I think stop motion could be another great medium (Lego science creations! Play doh or lego, a cell phone camera and a kid-written script!

We are attracted to cartoons because of the lack of detail in the human face, which helps us see ourselves in the image. Kids excel at seeing themselves in stories. They also love retelling facts and stories. Use that to your advantage while planning content.

Maren: Such great ideas! I’ve found that putting on plays can be a fun way to do this too. Either having a play performed for them, where each piece of the science topic is a character (for really little ones), or having the kids take the concept they’ve learned and turn it into a play that they perform for each other (for older kids).

Melody: I also cannot recommend Nat Geo Kids enough, they are a resource that just seems to work so well. It’s filled with images, often videos, and really doesn’t shy away from using language that a kiddo many not know, which leads to super rich discussion.

Q: Any parting advice on scicomm for kids?

Anna: It seems obvious, but have fun with explaining science to kids! If you look like you’re enjoying yourself, they’ll be way more interested!

Elaine: Talking about risks – The easiest way is to ask your child questions, if age-appropriate, and to think about tone while asking them, and to pick the right moment. With my first grade twins, we started the conversation by asking them, “Do you have any questions about why the school closed suddenly?” This happened at breakfast when their routine changed abruptly; it gave us a chance to find out how much and what they already knew. It also gave us a chance to correct any misinformation. It is essential to be truthful, but not too detail-oriented, and know how much information to offer. Younger children need simple explanations backed up by positives, “Some people have been getting sick, we can stay healthy by___.” Help them realistically reframe their fears.

Matthew: I think it’s all been said… Put yourself in children’s shoes. Use storytelling and make it relatable. Be open and honest.

Melody: Also never shy away from the what may seem unlimited amount of “why’s?” Sometimes when I am working or volunteering with kids, I start a count for fun, how many “why’s” will I get. I’ve counted up to 52. It’s fun, it’s important, and it helps the kiddo connect dots.