Once a week, we will feature a new artist on the Lifeology blog! This week we are featuring Elfy Chiang, her story and and her work illustrating Lifeology courses with us! She has illustrated several Lifeology courses with us, many of which are still in production. You can see one of her public-ready courses here! Without further ado – meet Elfy! She is an illustrator and science communicator from Taiwan.

Tell us a bit more about yourself! How did you get into art?

Meet Elfy!

Hi, my name is Elfy Chiang.

Science and Art have always been my two main interests in life. I studied Biological Sciences at university and was inspired by some of the textbooks we had that came with animations explaining DNA and other complex things. Those visual tools helped me a lot along the way with my studies and encouraged me to combine my passions in science and the arts.

Can you describe what your illustration process usually looks like? Where do you draw inspiration?

I often draw inspiration from everyday life, nature, or the work of other artists. I like taking pictures of random things I find beautiful or interesting. There’s always something worth appreciating around us.

For me, it’s important to work on something I’m interested in. It’s a good start to an enjoyable process where I often produce something I can be proud of. I think this is also true for many artists.

Personally, I have a general interest in health and wellbeing, so illustrating Lifeology courses had been particularly fun and fulfilling to me.

When you are illustrating a Lifeology course, what is the first thing you do? What does your illustration process usually look like?

When illustrating a Lifeology course, I usually start by spending a little time researching. I look up keywords or points I’m not entirely sure about to help myself better understand the course. This can also help me avoid misinterpreting the messages with my illustrations. At the same time, I look for as many relevant images as possible for initial ideas. With all this, I develop an illustration style that I think will fit the course.

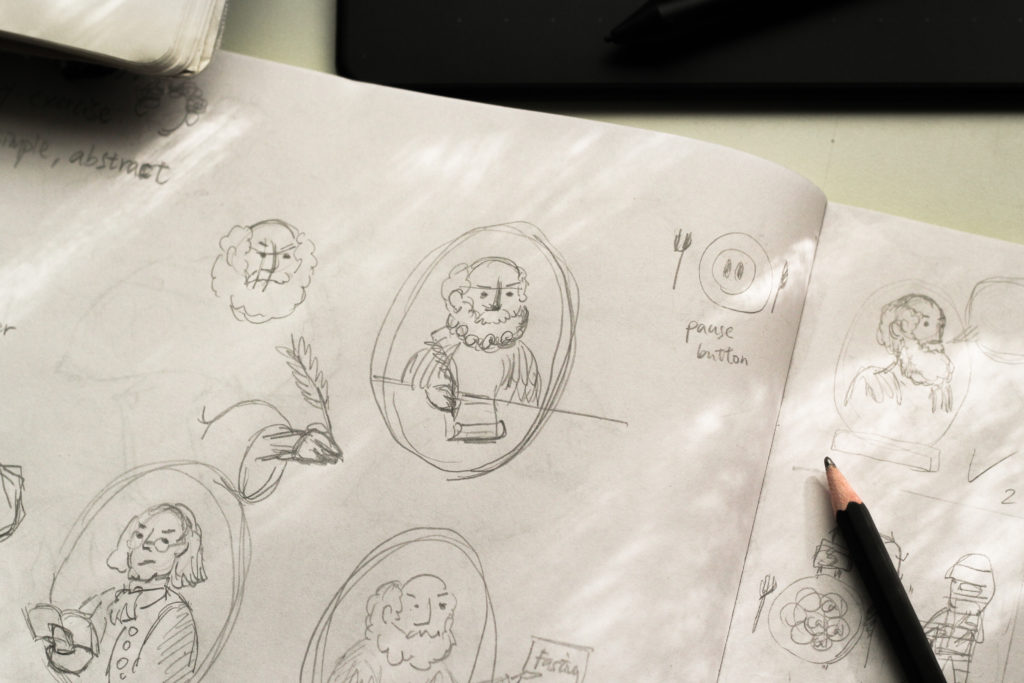

A sketched storyboard Elfy created for the intermittent fasting course.

Researching expands my view on the topic of each course and is key to storyboard brainstorming. It’s how I warm up my creative engine. This stage can sometimes take up more time than expected but definitely comes a long way in terms of planning.

What I also love about researching is that I always learn something new and interesting! For example, one of the Lifeology courses I had illustrated recently is about intermittent fasting, a topic that I hadn’t paid too much attention to before and thought it was just a method taken to the extreme for people who wanted to lose weight. But when I read the course and did extended reading based on it, I found out that fasting can trigger autophagy, a mechanism in our cells that removes misfolded proteins harmful to our bodies. And this is something that anyone, looking to lose weight or not, can benefit from!

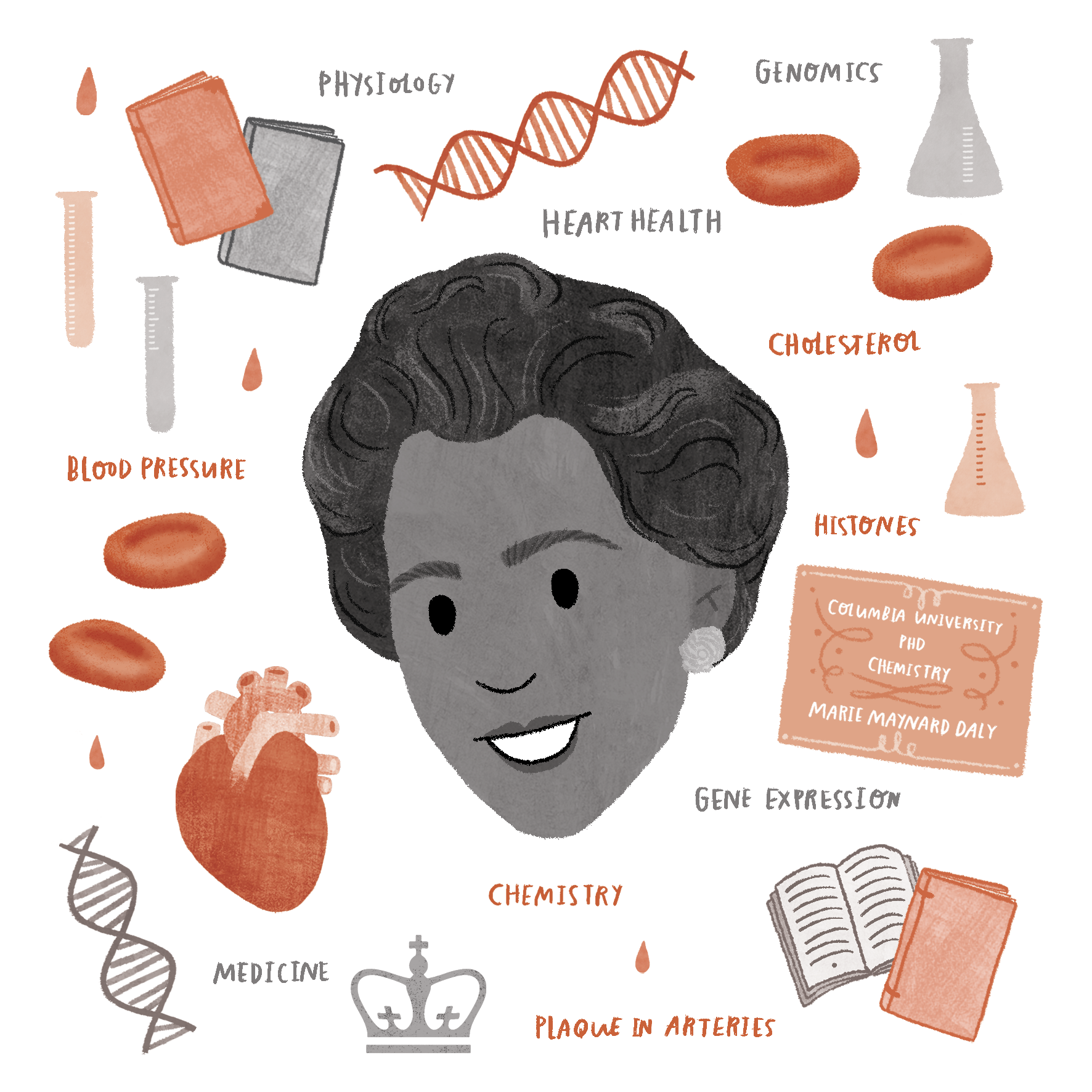

Elfy’s illustration of autophagy, a cellular recycling process that can protect the brain and other parts of the body from the impacts of misfolded proteins (like cognitive decline and dementia). Autophagy is activated when the body’s nutrient levels are low, such as during fasting!

How is illustrating a Lifeology course different from other science illustrating you’ve done?

The unique mini-flashcard format of Lifeology indicates the goal of the courses – to help people learn something useful within a short period of time while having a fun and positive experience. With this in mind, I make sure the illustrations are colourful and easy to understand at first glance and hold a consistent visual storyline.

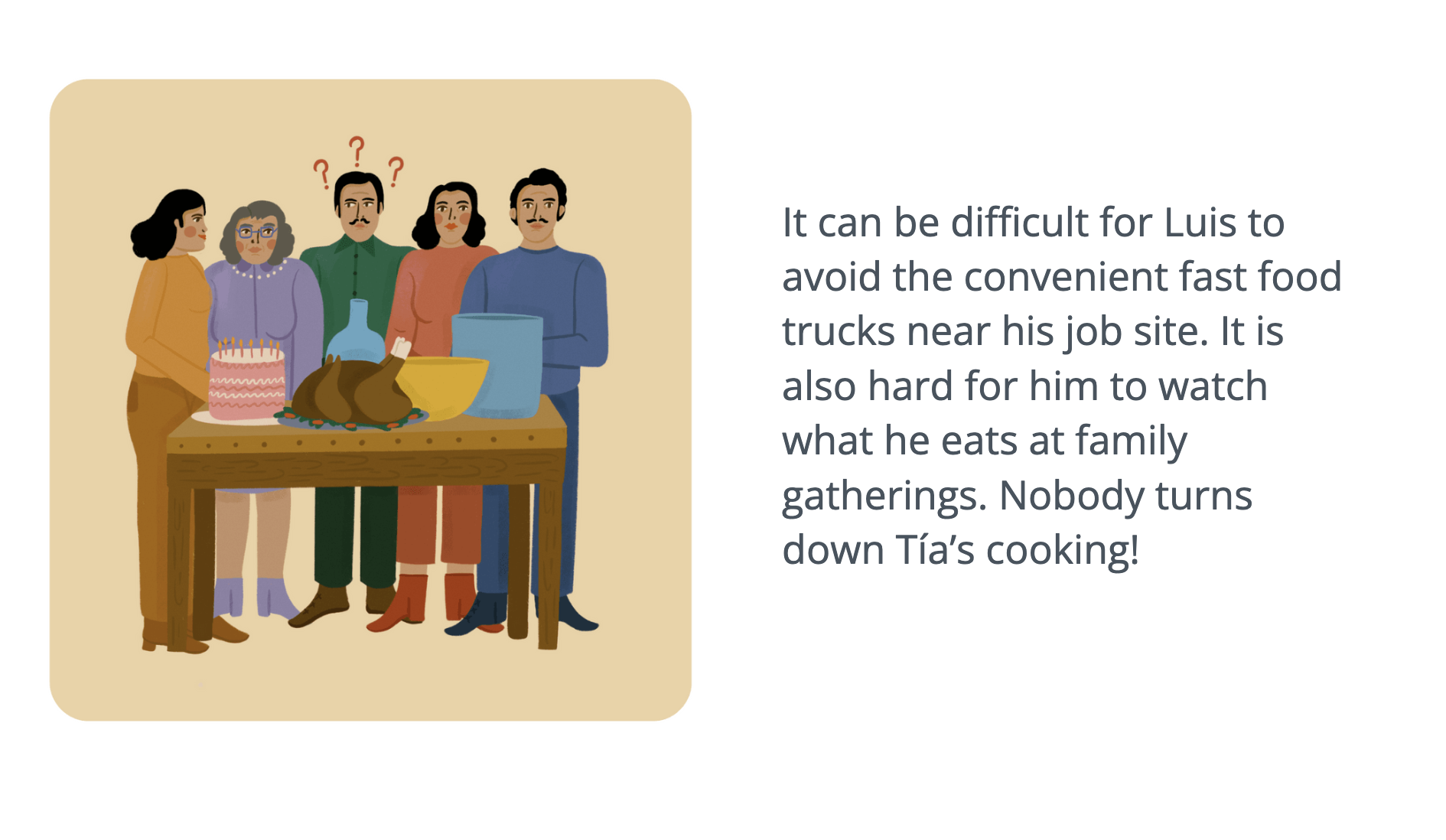

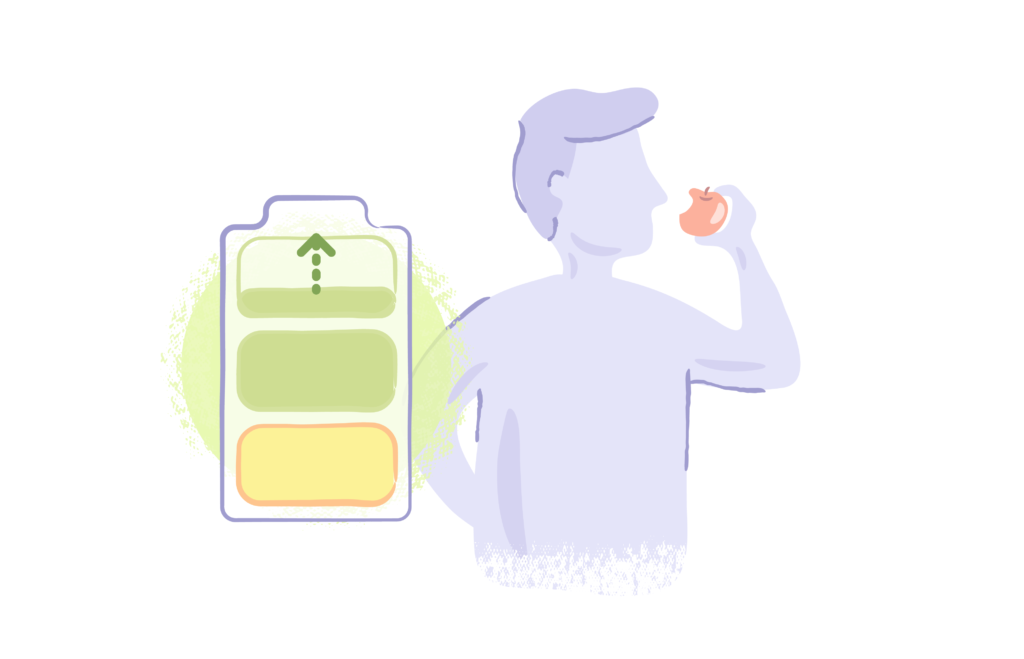

The other unique thing about Lifeology is that the content is aimed at a wide audience. Creating characters or using metaphors people can easily relate to is also key to building an engaging and memorable learning experience. For example, I used batteries as a metaphor for the energy level of human bodies in the intermittent fasting Lifeology course. I wanted to use the idea that eating is just like recharging energy to our bodies, to help readers better understand the changes we go through when we eat or fast.

Overall, I create the card illustrations for a Lifeology course under the mindset that science is everywhere, for everyone, and full of fun.

Elfy’s illustration of eating like being the recharging of a battery, which needs to run low in order to burn fat.

What tips or advice would you offer another artist working on illustrating a Lifeology course?

To me, illustrating a Lifeology course is like being excited about a science school project and feeling the need to draw pictures to tell everyone about it. So having some level of interest is a good place to start.

Lifeology is full of courses with science and health-related knowledge we can apply to our everyday lives. You don’t have to be an expert or have a background in science to illustrate a course. As long as you are ready to learn something new and have the enthusiasm to share it with others in a creative way, then you are set for a fun and creative experience.

Why should more scientists work with artists?

Visual language is universal and efficient. It is a powerful communication tool that we use almost everywhere in life. Scientists can benefit from using this tool to communicate their work where things are often complicated.

Visual graphics not only speed up the communication process but also create a more professional, engaging and memorable experience for both scientists and their audiences. It’s how scientists can show that they value their work and that they know it’s important to communicate it to others. They respect their own work as well as the people they are communicating with.

Art is also very flexible and can be applied almost everywhere. I have worked with scientists and educators who had used visual graphics for many purposes, from academic publications, to grant proposals, to conference talks and posters, to lectures, to healthcare information for patients, and even job interviews. You name it. Very often I hear from them that they’ve received more feedback, encouraged more discussion, and gotten higher citation counts on their publications when they used designed graphics. These positive effects are key to increasing research impact, which is what scientific research is all about.

What tips or advice would you offer scientists and artists working on art/illustrations for any purpose?

For Scientists

Make sure your message is clear and concise. Be precise with the take-home message you wish to deliver. Communicate this clearly to the artist you are working with in simple words. Try not to push for too many details to be included in your graphics. I’ve worked with scientists who weren’t entirely sure what they wanted to say with the images and kept changing their minds on what to or what not to include along the way. This eventually led to a time-consuming experience for both of us.

Set achievable goals and deadlines. Have a clear purpose and list a few things that you want to achieve with the content. For example, if you will be using the graphics at a conference, then you can set a goal of having more people come up to you to talk about your work or seeing more raised hands on a Q&A session (with good intentions of course). Or if you are creating a leaflet for patients, you might want to see them coming back with a more positive take on their conditions or treatments. Communicate to the artist the problems that you might want to solve and the possible outcomes you wish to see.

Set a reasonable deadline and schedule time for initial discussions and revisions with the artist. Nobody likes to work on a tight deadline, but nobody likes to work on a project that takes longer than it needs to, either. So work out a reasonable project timeline for both of you.

One way to save time is to work out a draft with the artist before agreeing to move on to the actual artwork. This way you would save time having to ask for too many changes afterwards.

If there is a visual style you wish to create, provide example images to the artist rather than just describing it in words. This can help point the direction on what you have in mind at an early stage while the artist creates something that better meets your expectations. Provide suggestions on what may cater to your audience. However, it’s also good to keep in mind that you don’t have to stress on the design or layout too much at early stages. It’s the artists’ job to visualize your message. Allowing some flexibility between the two of you would give you a better chance on exploring potential outcomes and come up with the best solutions possible.

For Artists

Start with interest and do research. Like I mentioned before, working on a topic that you are interested in leads to a more enjoyable experience. Be prepared to learn new things and do some research when you start. Researching helps you develop ideas and deliver more accurate information. Cross-examine the information you find and make sure that you get your information from reliable sources. Ask for the scientists’ advice if you’re not sure where to look!

Tailor the artwork to the purpose and the audience. In addition to understanding the key messages, find out where and why the scientist will be using the art and who will be seeing it. These factors will decide the ideal format or style of the artwork. For example, if you are creating an abstract figure summing up the scientist’s work for their academic publications, very often they will also want to use these figures at a talk or lecture. This is when it’s a good idea to create something that would look good online, in print, and also from a distance when projected as a slide show.

It’s also important to understand the audience or context to tailor what you create to their needs. For example, a colourful and vibrant design may provoke attention and interest in younger audiences, which will be great for a science summer camp poster, but would seem distracting or out of place in an academic journal.

For Both Scientists and Artists

Most importantly, communicate with each other as much as you can and make sure that you are on the same page along the process. Respect each other’s time and be responsive. Scientists are often very busy and every artist works differently. Work together to explore different possibilities on the solutions and on how you can collaborate. Be open-minded and expect to learn from each other.

Don’t be shy to ask each other questions and have fun creating!

Connect with Elfy here!

Want to illustrate a Lifeology course or create your own (Elfy can be your artist!)? Get started here.