Each month, Lifeology hosts a SciArt Reading Club, which is a live chat about a visual science communication-related reading, over on our Slack Workspace. We invite artists, scientists, and science communicators to collaborate in the Slack space. Alice Fleerackers, an interdisciplinary researcher studying science communication and digital journalism, moderates our SciArt Reading Club chats. Join future chats by joining the Slack and signing up for the newsletter here. The May chat is Wednesday, May 26 at 12 p.m. ET.

For April, the reading was Engaging Māori with qualitative healthcare research using an animated comic, by Kearns and colleagues (2020) (PDF link).

In this short and sweet little paper, the researchers show how comics – when paired with culturally appropriate study design – can encourage underrepresented groups (in this case, the Māori, an Indigenous people of New Zealand) to participate in healthcare research. They discuss possible reasons why this recruitment strategy can be so successful, including the use of representative illustrations, collaborations with community members, respect for ethics, and other ways to engage and build trust.

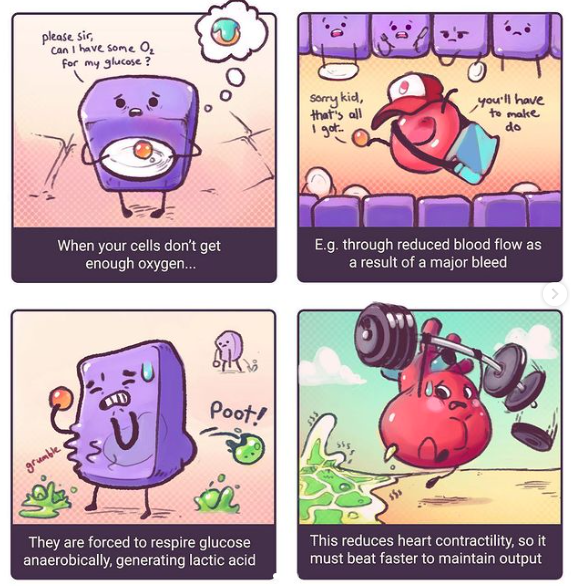

Our SciArt Reading Club live chat started with a discussion of comics and people’s experiences creating comics for science communication. Those participating in the chat (including science communicators, scientists and artists) expressed that comics are an engaging format for science communication. They can make science and health information more accessible, concrete, understandable and fun.

Image: Creative Ki

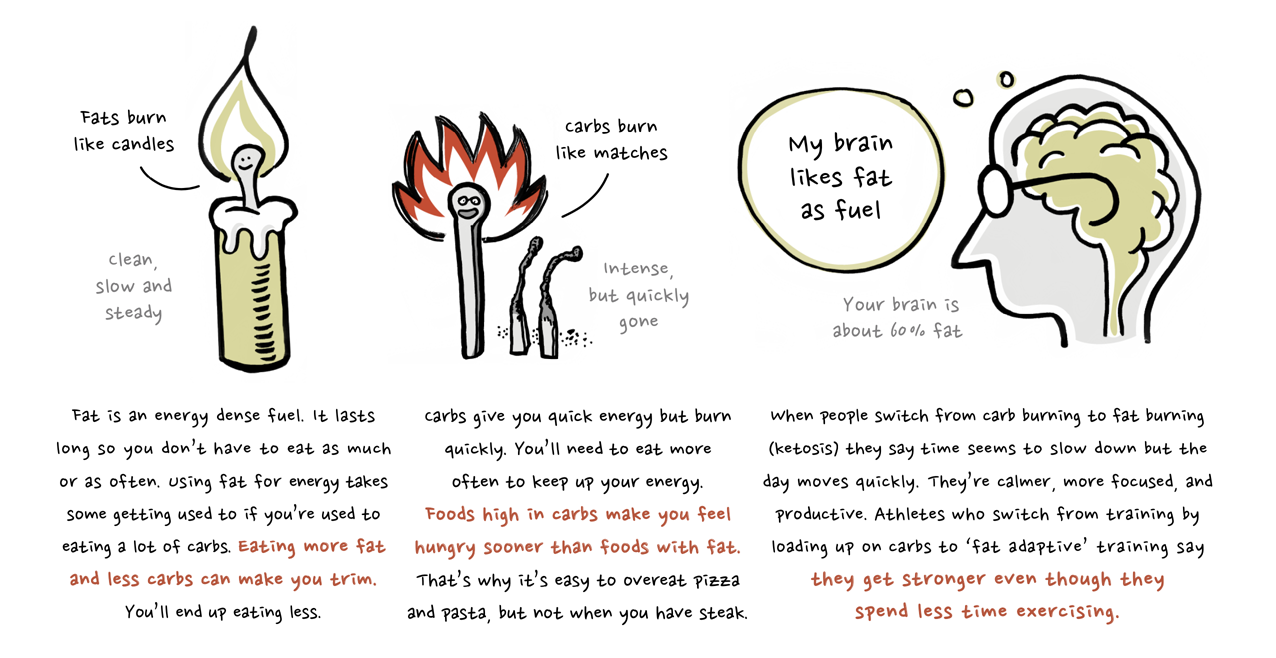

“I’m working on a book that explains nutrition to kids — and their parents. I use comics to get away from the jargon and patronized tone often used by doctors and nutritionists.” – Creative Ki.

But people participating in our chat also agreed – comics are also more difficult to create than most people might assume! It takes time and often lots of collaboration, with an artist for example, to break down the information you want to include in the comic into a “script” that has discrete actions or “frames.”

In our chat, most of us also agreed that despite the benefits of comics claimed by Kearns and colleagues, comics are also not accessible and inclusive by default. It is difficult to make comics ADA compliant, for example. And while comics can make science, health and other technical information more accessible and understandable through a combination of simple text and complimentary visuals, they can also be confusing if they aren’t done well.

“Done well they can be great. Poorly and they can be more confusing. The fact that comics are generally easy to understand is why things like Ikea instructions are basically wordless comics.” – Michael Safranek

“Using comics does tend to make subjects more concrete…” – Raymond K. Nakamura, Ph.D.

Just as in any form of storytelling, it is also critical to consider representation, relatability and cultural relevance of the characters, settings and events depicted in a comic for a specific audience. It is difficult or impossible to make a comic inclusive without considering these elements. At the same time, it is important to work with people who identify with or represent the communities you are trying to reach with a comic. This collaboration during content creation helps to build trust and is important for preventing reinforcement of stereotypes, misrepresentation or appropriation of culture.

“A lot of times, other groups involved tend to make decisions for the group they are trying to work for. There are assumptions as to what is right for them. Including them from the beginning can help all parties understand what is needed by the group they represent and build a lot of trust.” – Rushika Pandya

“I do think that if you have a particular audience in mind, that research and time spend to create culturally relevant examples and dialogue is critical. This can be difficult when you just have a ‘general’ audience in mind.” – Paige Jarreau

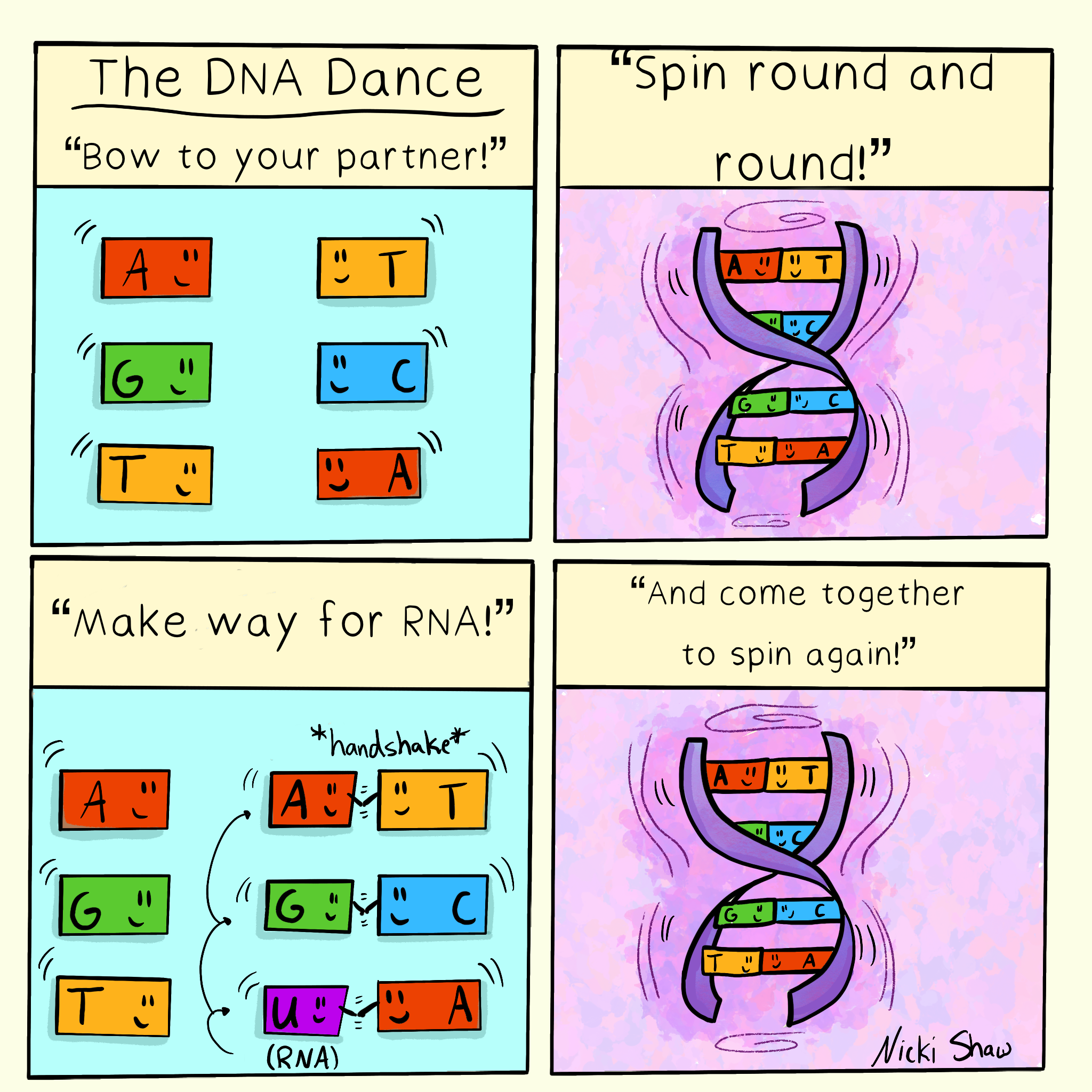

Image: Courtesy of Nicki Shaw, a SciComm cartoonist and Lifeology community member

Kearns and colleagues consulted with Māori community leaders in creating their comic, which featured a cute pair of lungs talking about how in order to better understand how to treat asthma, we needed to learn more from experts… not doctors, but people with asthma. The comic was designed to encourage patients with asthma, especially Māori patients, to consider participating in an asthma research study. Its success reaching Māori patients with asthma is a testament to the importance of early collaboration with target communities in the design and creation of educational materials.

“I think being inclusive doesn’t mean everybody should be represented but those who are the focus deserve good attention and participation in the decisions.” – Helder Lira

“It could be risky to make a comic in the style of a culture if you are not from it.” – Raymond K. Nakamura, Ph.D.

“Yes. I can’t see any way to do it without a) hiring an artist from that culture or b) working extremely closely with several cultural ‘liaisons.’” – Alice Fleerackers

Image: Ciléin Kearns Instagram

During our chat, we also discussed the benefit of using non-human or animal characters in comics. The animated comic in this study by Kearns and colleagues featured a pair of lungs, not people, as characters. The authors believe this helped recruit a more diverse group of participants, writing that “Simple abstract characters can be more universal, allowing any viewer to project their identity and ‘see themselves’ in the visual material.”

“It was interesting that they mentioned the use of the lungs as characters which are not associated with any one kind of person, although I suppose their behaviours and language could be other cues. Using comics does tend to make subjects more concrete, which can be limiting if a human character. The use of animals in children’s stories seems to be in part a way to seem diverse without focussing on a particular group and perhaps allow anyone to associate themselves with them.” – Raymond K. Nakamura, Ph.D.

“There is something about having this problem externalised as a character which allows people to engage and react to it differently than if it is part of their own body. When I work with people with OCD I talk about their OCD as being a bully they need to stand up to, and it can be really helpful. I think comics are a medium where it’s easy to do that anthropomorphism.” – Michael Safranek

“From what I remember about comics theory, leaving the character ‘vague’ or ‘simple’ is supposed to help the reader project themselves into the story. I guess that principle could be applied to any modality.” – Michael Safranek

But are non-human characters always better for comics? In our chat, we concluded that it depends on the audience and context. “Cute” or non-human characters might not be appropriate in more serious contexts, like in educational materials given to a patient immediately after a serious health diagnosis.

“Perhaps cartoons are more suitable to spread awareness without raising an alarm where appropriate and make it fun at the same time.” – Rushika Pandya

We invite you to read the Kearns et al. paper and tell us your own thoughts about how comics can be effectively used for science communication and what factors are important to consider in creating an effective comic! Join our Slack Workspace and #SciArt-reading-club channel in the Workspace to share your thoughts!

We also have an upcoming Lifeology University SciComm Program on how to create a science comic – keep an eye out or sign up for the free program to get e-mail alerts!